Sometimes you find a quote that so precisely illustrates a historical or religious theme that it is hard to resist using it in writing or teaching. They cry out for a “Discuss.” Today I have a beauty for anyone interested in Global or World Christianity, and for Eurocentrism.

By way of background, this present month commemorates one of the greatest anniversaries in American religious history, namely the landing of the Mayflower in 1620. It is a telling comment on present American concerns and obsessions that this has been so little commemorated in anything like the way it might have been in earlier decades. Why don’t we all dress up for pageants any more? Debates over the ludicrous “1619 Project” have perhaps tainted any such celebrations. Thankfully, we also have a magnificent contribution by a real historian in John Turner’s recent They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty (Yale 2020).

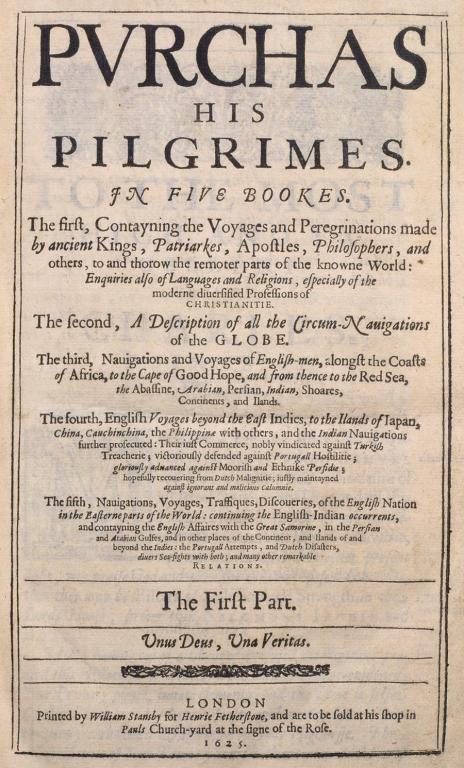

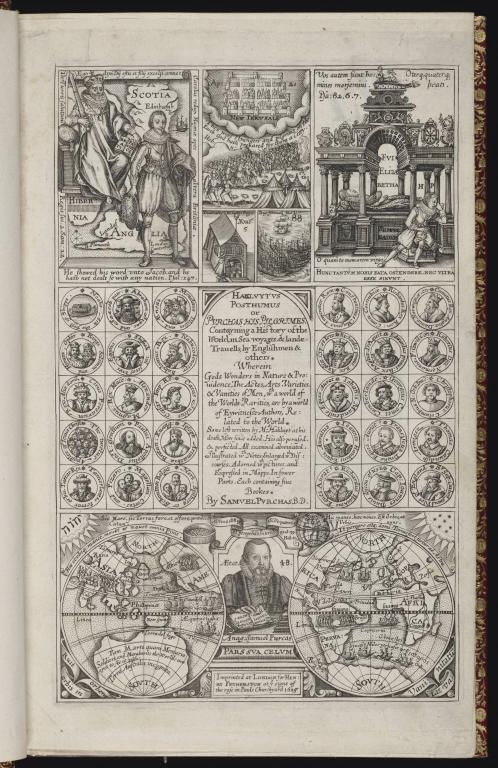

But I want to look at another set of “pilgrims” who in their day were vastly more celebrated than the Puritan migrants known to Americans. The author was Samuel Purchas (1577-1626), an Anglican cleric who served as chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbott. Although Purchas did not travel much himself, he became one of the best-known travel writers in English, collecting the stories of various writers, especially the legendary Elizabethan, Richard Hakluyt. In 1614 he published Purchas His Pilgrimage: or Relations of the World and the Religions observed in all Ages and Places discovered, from the Creation unto this Present. In 1625, there appeared the massive Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes.

Purchas’s Pilgrimes is an epic read, a hugely comprehensive account of global history and geography, and there is a great deal to say about it. Here, though, I will just concentrate on one aspect, namely its view of Christianity in the world of his time, which was exactly the era of those well-known Pilgrims who traveled to Plymouth Colony.

Purchas waxes very lyrical on the subject of Europe, and he can be described as Eurocentric on steroids. Europe and Europeans have been everything, done everything, and been everywhere:

But what speake I of Men, Arts, Armes ? Nature hath yeelded her selfe to Europaean Industry. Who ever found out that Loadstone and Compasse, that findes out and compasseth the World ? Who ever tooke possession of the huge Ocean, and made procession round about the vast Earth ? Who ever discovered new Constellations, saluted the Frozen Poles, subjected the Burning Zones? And who else by the Art of Navigation have seemed to imitate Him, which laies the beames of his Chambers in the Waters, and walketh on the wings of the Wind?

And is this all ? Is Europe onely a fruitfull Field, a well watered Garden, a pleasant Paradise in Nature ? A continued Citie for habitation ? Queene of the World for power ? A Schoole of Arts Liberall, Shop of Mechanicall,Tents of Military, Arsenall of Weapons and Shipping ? And is shee but Nurse to Nature, Mistresse to Arts, Mother of resolute Courages and ingenious dispositions ? Nay these are the least of Her praises, or His rather, who hath given Europe more then Eagles wings, and lifted her up above the Starres. I speake it not in Poeticall fiction, or Hyperbolicall phrase, but Christian Sincerity.

But then he comes to a passage that could legitimately be incorporated into any and every history of Global/World Christianity, to suggest what later generations were reacting against:

Europe is taught the way to scale Heaven, not by Mathematicall principles, but by Divine veritie. Jesus Christ is their way, their truth, their life ; who hath long since given a Bill of Divorce to ingratefull Asia where hee was borne, and Africa the place of his flight and refuge, and is become almost wholly and onely Europaean. For little doe wee find of this name in Asia, lesse in Africa, and nothing at all in America, but later Europaean gleanings. Here are his Scriptures, Oratories, Sacraments, Ministers, Mysteries. Here that Mysticall Babylon, and that Papacie (if that bee any glory) which challengeth both the Bishopricke and Empire of the World ; and here the victory over that Beast (this indeed is glory) by Christian Reformation according to the Scriptures.

Europe is the home of the Catholic church, and also (in his view) the better form of Protestant religion that has challenged it. Outside Europe, there is no trace of Christianity that matters. It is “almost wholly and only European.”

Discuss!

Not to mention God giving “a Bill of Divorce to ingratefull Asia where hee was borne, and Africa the place of his flight and refuge.” Christianity in African and Asia? That is SO first millennium.

God himselfe is our portion, and the lot of Europe’s Inheritance, which hath made Nature an indulgent Mother to her, hath bowed the Heavens over her in the kindest influence, hath trenched the Seas about her in most commodious affluence, hath furrowed in her delightfull, profitable confluence of Streames, hath tempered the Ayre about her, fructified the Soyle on her, enriched the Mines under her, diversified his Creatures to serve her, and multiplied Inhabitants to enjoy her ; hath given them so goodly composition of body, so good disposition of mind, so free condition of life, so happy successe in affaires ; all these annexed as attendants to that true happinesse in Religion’s truth, which brings us to God againe, that hee may bee both Alpha and Omega in all our good.

Or as a later enthusiast put it: Europe is the Faith, and the Faith is Europe.

Can I just say that, to put it mildly, those are not my views? But Purchas does a superb job of presenting that long-standing Eurocentric view of Christianity, and the providential view of how Europe’s God made the continent his cherished prize, ready to claim possession of the whole world. At once he reflects contemporary thought, but also formulates it in a way that would mold the thought of later generations, of missionaries, migrants, and empire-builders. The Earth is Europe’s, and the fullness thereof.

Purchas’s Pilgrimes was a very long-running best-seller, and it found some interesting readers through the centuries. In 1797, Samuel Taylor Coleridge picked up the book when he was feeling out of sorts, and he found a passage that intrigued him:

In Xandu did Cublai Can build a stately palace, encompassing sixteen miles of plaine ground with a wall, wherein are fertile meddowes, pleasant springs, delightful streams, and all sorts of beasts of chase and game, and in the middest thereof a sumptuous house of pleasure, which may be moved from place to place.

Hmm, maybe you could even make some kind of poem based on what Kubla Khan decreed in Xanadu?