Through the years, I have posted repeatedly at this site on religious images in art, and what they can tell us about ideas and debates in earlier eras. Scholars still pay insufficient attention to the incredible resources that lie in such visual imagery: we can be a very text-bound lot.

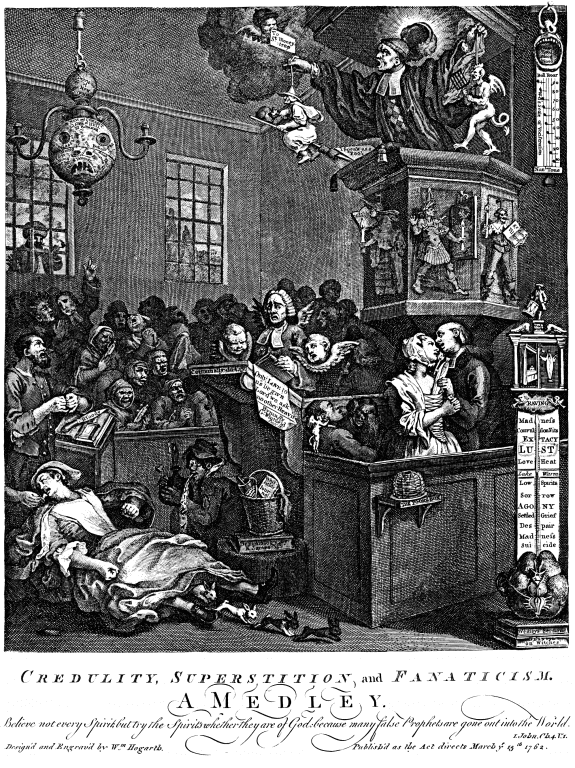

As an example, I offer William Hogarth’s astonishing picture of religious fanaticism in eighteenth century England, his 1762 response to the Methodist Revival – and every point applies to the critics of America’s contemporary Great Awakening. The picture is entitled “Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism.” The targets are, basically, the Wesleys and George Whitefield. (SPOILER: Hogarth did not approve of them or their ideas).

You can see a much more detailed image here, and it really does repay careful analysis. Click on that image to expand it even further.

Every square inch of the picture demands examination – take your time! The number of points made about religious extremism, or what we might call “cultish” fanaticism, is enormous. This one picture supplies evidence that we would otherwise need to draw on literally hundreds of contemporary tracts and pamphlets to supply. You don’t have to agree with the critique to find here a superb historical source. This also follows on from my recent posts about “cults” in American history, and how they have morphed to respond to our own new technologies.

So what do we see in Hogarth’s picture? Well, first note the idea that the bizarre beliefs and practices are of the Devil: the text quoted is “Beloved, believe not every spirit, but try the spirits whether they are of God: because many false prophets are gone out into the world.” (1 J0hn 4.1). The audience is made up of the dumb, gullible, and hysterical. The preacher is feeding them nonsense about witchcraft and the devil. See the fanatic with the bloody knife, ready to leap into action.

At the front we see a woman apparently giving birth to rabbits. That is a reference to a famous hoax of the era, as Mary Toft reported just such a mishap in the 1720s, creating a national and indeed European sensation, and baffling the most skilled doctors of the era. Arguably, Mary Toft, the Rabbit Queen, became the most famous English woman of the eighteenth century internationally. Karen Harvey has a wonderful recent account of the case under the title The Imposteress Rabbit Breeder: Mary Toft and 18th-Century England. Hogarth uses Mary here as a symbol of gullibility. If you believe all the signs and wonders the revivalists are claiming, he suggests, then why not believe that ridiculous “miracle”? You can also see references to some other ghost and poltergeist stories of the era, such as the Tedworth Drummer.

Note especially the strong sexual currents in the critique of extremist religion – see the amorous couple on the right.

And do see the “thermometer” at the right, with the successive phases of revival mania duly marked, including madness, convulsions, ecstasy, lust, despair, raving, and suicide. Another gauge measures the noise levels, the “vociferation,” being produced at the meeting, up to the full shrieking bull roar.

At the top of the image, we see the prevailing figure of “St. Money-Trap.”

Look hard and you’ll see references to several of the great revivalists of the time. The globe commemorates William Romaine – the London evangelical pastor who in his day was quite as well known as the famous preachers we remember. The pulpit bears a quote from a hymn by George Whitefield, and there is a copy of Whitefield’s Journal. A copy of Wesley’s Sermons is stashed at the far lower right. What other Easter eggs am I missing?

Is that a Muslim Turk at the window, scoffing at the foolish Christians?

Looking at the image in general, I think back to what Charles Dickens wrote about the US in his American Notes (1842), with his classic discussion of the popularity of wild enthusiastic religion:

Wherever religion is resorted to, as a strong drink, and as an escape from the dull monotonous round of home, those of its ministers who pepper the highest will be the surest to please. They who strew the Eternal Path with the greatest amount of brimstone, and who most ruthlessly tread down the flowers and leaves that grow by the wayside, will be voted the most righteous; and they who enlarge with the greatest pertinacity on the difficulty of getting into heaven, will be considered by all true believers certain of going there: though it would be hard to say by what process of reasoning this conclusion is arrived at. It is so at home, and it is so abroad.

But he wanted to be strictly fair to the Americans, and stressed that “I am not aware that any instance of superstitious imposture on the one hand, and superstitious credulity on the other, has had its origin in the United States, which we cannot more than parallel.” And even in 1842, he still supported that claim by citing the case of “Mary Toft the rabbit-breeder.”

I have only scratched the surface here, and you can make plenty of discoveries for yourself. But if you are writing about eighteenth century revivalism without citing visuals like this, you really are missing a substantial part of the story.

Oh, and just to be fair and balanced. Hogarth also made fun of the mainstream non-revivalist Anglican church and its clergy in his 1736 depiction of The Sleeping Congregation.