During this pandemic semester, I had the privilege of teaching a graduate seminar on Women and Religion. Since we couldn’t do everything I usually do, we did some new things I thought would be beneficial to graduate students entering a more social-media and virtual-oriented job market.

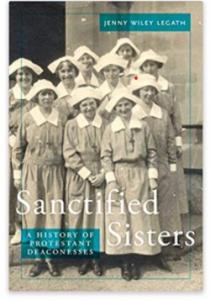

We learned how to discuss scholarship and connect with scholars on social media, through our #5320women Twitter discussions on Tuesday afternoons (just search for our hashtag). We practiced giving virtual conference papers and creating academic vlogs. We also practiced writing blog posts that featured our scholarship for a more public audience. Instead of writing traditional book reviews, each of my 10 students submitted a book review a-la-blog. The class voted on which submission they thought best captured the academic essence of an academic book review that was also written in a more engaging public-facing style. Today I present to you the second place people’s choice winner of our semester work, following Anna Wells top-choice post from two weeks ago. Benjamin “Jack” Young is a senior undergraduate History and Religion major who braved a Graduate Seminar this semester. He is currently applying to PhD programs, so look out for him! His winning book review features Jenny Wiley Legath’s Sanctified Sisters: A History of Protestant Deaconesses. Congrats, Benjamin Young!

Every fall, Wake Forest University’s Demon Deacon entertains college football fans and lives up to his reputation as one of the most peculiar mascots in the sport. The Demon Deacon first appeared at Wake Forest football games in the 1940s, when a student named Jack Baldwin donned a black-and-gold suit and top hat and danced in the stands and on the sidelines. Baldwin hoped to look, as he later reflected, “like you would think an old Baptist Deacon would dress up” (Wake Forest was affiliated with the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina until 1986). Over seventy-five years later, the Demon Deacon continues to stalk the Wake Forest sidelines. With his unsettling blend of sinister saintliness, the Demon Deacon evokes Dante’s Inferno more than the lay leadership of your local Baptist church.

As lighthearted as the Demon Deacon is, he is also a legacy of the early twentieth-century southern Protestantism in which Wake Forest was embedded and his comedic caricature developed. In Southern Baptist churches at the time, deacons were people of good repute, subservient to the pastor, who volunteered to serve in a variety of formal and informal capacities within their congregations. It is all too easy to gloss over the fact that the Demon Deacon is gendered male, reflecting the reality that in the early twentieth century Southern Baptist deacons, with few exceptions, were exclusively men. Yet in the same era that the Demon Deacon rose to prominence, other Protestant denominations in the United States perceived the diaconate quite differently. In Sanctified Sisters: A History of Protestant Deaconesses, historian Jenny Wiley Legath sheds light on a largely forgotten movement within American Protestantism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Legath’s book examines how thousands of Protestant women, drawing inspiration from the biblical figure of Phoebe (Romans 16:1-2), took the title and vocation of “deaconess.” Originating in England and Germany in the mid-nineteenth century, the deaconess movement prospered in America from the 1880s through the 1920s, taking root in German-American denominations and among Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Methodists. Spurning marriage and family life, deaconesses lived communally and devoted themselves to serving in hospitals, orphanages, and homeless shelters. Using a wealth of archived records and oral histories from these deaconess communities, Legath recounts how these Protestant women constructed a unique spiritual vocation for themselves.

Legath argues in Sanctified Sisters that deaconesses had to maneuver a constrictive set of gender norms at the turn of the twentieth century. In a Protestant culture that idealized women as wives and mothers, deaconesses selectively adopted these gendered expectations to justify their celibate, communal callings. Deaconesses did not directly challenge the prevailing cultural assumptions within Protestant churches that valorized marriage as normative. As Legath states, they instead portrayed their calling as “sanctified spinsterhood,” a narrowly defined, non-threatening alternative to marriage that the Bible ha d authorized in the figure of Phoebe (Legath, 47). Indeed, though deaconesses were not mothers, they frequently cited their maternal qualities as proof that God had called them to minister to needy children. “It seems,” a fictional deaconess in an 1893 novel suggests, “as if God wants some of us to be mothers of humanity’s orphans” (Legath, 49). By co-opting the cultural expectations within their churches that had traditionally restricted women to home and hearth, deaconesses carefully articulated their calling not as a betrayal of their God-given feminine qualities, but as an alternate use of them.

d authorized in the figure of Phoebe (Legath, 47). Indeed, though deaconesses were not mothers, they frequently cited their maternal qualities as proof that God had called them to minister to needy children. “It seems,” a fictional deaconess in an 1893 novel suggests, “as if God wants some of us to be mothers of humanity’s orphans” (Legath, 49). By co-opting the cultural expectations within their churches that had traditionally restricted women to home and hearth, deaconesses carefully articulated their calling not as a betrayal of their God-given feminine qualities, but as an alternate use of them.

Sanctified Sisters also depicts how deaconesses reckoned with their unmistakable similarities to Catholic nuns. On the one hand, deaconesses unmistakably took inspiration from nuns in their commitment to communal living, chastity, and charitable service. On the other hand, the feverish anti-Catholicism prevalent in American Protestantism in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century forced deaconesses to constantly distinguish themselves from nuns in order to avoid charges of “Romanism.” As an example, Legath describes how deaconesses battled with their denominations for permission to wear a simplified common outfit because male denominational leaders feared the deaconesses would look too much like nuns. Deaconesses also borrowed tried-and-true Protestant maxims to elevate themselves above nuns, describing the calling of a Protestant deaconess as “an act of faith, freely rendered” but the life of a Catholic nun as a “good work, enforced by vows” (Legath, 101).

Historians of women and religion will take note of Legath’s critique of a prior generation of scholarship that depicted the Protestant deaconesses of the early twentieth century as forerunners to the ordained female ministers of the late twentieth century. Legath argues conclusively that deaconesses did not perceive themselves as female equivalents to deacons and, moreover, rarely preached, performed ceremonies, or administered sacraments in the context of the Sunday church service. Even when female ordination movements gained momentum in some Protestant denominations in the mid-twentieth century, most deaconesses were ambivalent and “declined to rap on the stained glass ceiling of ordination.” Readers interested in the history of women in ministry will appreciate Legath’s nuanced perspective.

For all its detail, Sanctified Sisters will leave some readers wanting more. Although Legath hints at the formative role of the Oxford Movement and the Social Gospel in the creation of the modern Protestant deaconess, those looking for a detailed theological genealogy will be disappointed. Also left unexamined is the reasons for deaconesses’ overwhelming concentration in the Midwest and Northeast and their absence in southern Protestantism. Nevertheless, Sanctified Sisters is a fascinating book full of new insights for even the most seasoned readers of religious history. Its subject has relevance for ongoing conversations concerning women in ministry today. As deaconess groups shrunk through the latter half of the twentieth century, women have taken up the ordained roles once restricted to men in many Protestant denominations. Even in Wake Forest’s former denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, where conservative stances on women in ministry have historically barred women from the diaconate, some theologians have recently begun to reinterpret passages like Roman 16:1-2 to permit female deacons.

All that to say, the Demon Deacon might one day have an equally iconic Demon Deaconess with him on the sidelines.

Benjamin Young is a History and Religion major at Baylor University, graduating in May 2021.