. . . But my students’ family history papers have taught me not to ignore them.

The end of the semester in my introductory American history survey classes is the time of year when I get to read one of my favorite student assignments: family history essays. These papers always include some fascinating stories, but they have also given me an education in the history of the white rural South that has changed my perspective on race and politics in contemporary America.

If you, like me, did not grow up in the South or outside of a town or city, rural white Trump-loving Americans might be an unfamiliar culture. In graduate school, I read Wayne Flynt’s Dixie’s Forgotten People: The South’s Poor Whites, but compared to what I read on other groups of Americans, I knew relatively little about rural white southern culture. That continued even after I moved to Carrollton, Georgia, to teach at the University of West Georgia, a second-tier regional comprehensive university whose campus is within a ten-minute drive of cows and pastureland and whose students include many who arrive from rural counties and small towns of less than 2,000 people. More than 90 percent are from Georgia, and many of the rest are from Alabama, since we are less than twenty-five miles from the state line. Not all of these southern students are white, of course; nearly 40 percent are African American, and 10 percent are Hispanic, and I have learned a lot from reading their family histories, too. But most of the other 50 percent of our students come from white, lower-income southern families whose family histories are usually closely intertwined with the historical developments that Flynt chronicled. When I compared their histories to the histories of African American students, the result was eye-opening – and not in quite the way I had expected.

I expected that the results of my family history assignment would show a contrast between the wealth and education that white families were able to accumulate over time with the lack of educational opportunities and the lack of wealth for Black families. This, after all, was what I had repeatedly seen in statistics about Black and white disparities in home ownership, land ownership, and overall wealth acquisition. The average white family has ten times the amount of wealth that the average Black family does. There’s no question that for the nation as a whole, there is a massive wealth gap between Black and white Americans. But that is not true for our particular student demographic – and the family histories that my students write explain why.

My assignment requires students to use census records and other materials from our university library’s Ancestry database to trace their family history back to at least the 19th century, if possible, and then use interviews with older relatives to fill in some of the details and bring the story up to the present. Because the US census from the mid-19th century through 1940 required each household member to list their occupation and, for the later censuses, home ownership, literacy skills, and educational levels, these records allow a historian or genealogist to reconstruct a family’s migrations, education, and levels of wealth over time.

Not surprisingly, very few Black families in the South were able to own land or houses in the late 19th or early 20th century. The Black students in my classes who have traced their ancestry back to the mid-19th century have invariably found that if they had ancestors in Georgia in the 1870s or 1880s, the adults in the family had been born in slavery and were working as sharecroppers or tenant farmers during the eras of Reconstruction and the so-called “New South.” In every case that I have seen from my students’ family histories, those born in slavery never had the opportunity to learn to read and write after slavery ended, nor did they have the opportunity to own land. Occasionally, the next generation of the family managed to buy a small family farm in about 1910 or move to a house in town in Atlanta or another city and take a job as a hotel porter or domestic servant, but most of my Black students have found that their ancestors continued to work as sharecroppers until the 1940s.

Yet literacy levels for these non-landowning African Americans were surprisingly high. Although those born in slavery were highly unlikely to learn how to read and write, their children or grandchildren usually could, even if they had no more than a grade-school education or, in many cases, only a year or two of schooling. And when Black students interview their family members, the interviews usually reveal a strong commitment to education. Several of them have grandparents, for instance, who were teachers, school principals, or ministers – or, at the very least, they have a mother who may not have ever had a lot of money, but who at least earned an associate’s degree and wanted her children to go to college.

In one case last year, I discovered that one of my Black students’ great-great-grandfathers was the founder of a Black school in the early 20th century. He had been a sharecropper and had had only a few months of formal education, but after serving in World War I, he became a leader in his community, an elder in his church, and a strong proponent of education. He earned less than $1,000 a year delivering milk door-to-door during the Great Depression, but nevertheless, he helped found a “colored school” during the 1930s, and he sent every one of his children to college.

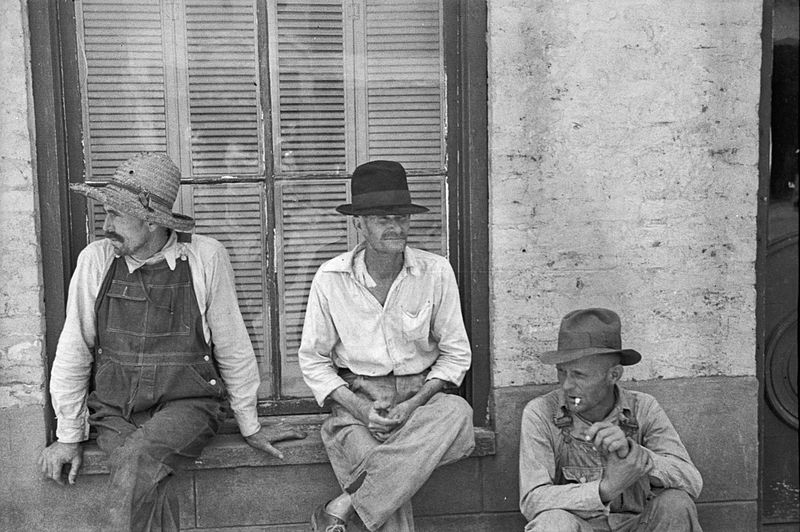

I have never found a comparable story among any of my white students. Instead, to my surprise, many of their ancestors were just as poor as those of their Black counterparts but had even less education. While, with the exception of those born in slavery, it is relatively rare to find Blacks in the census records I have examined from the early 20th century who could not read, this phenomenon was very common among the poorest whites. Even as late as the 1940 census, it is not unusual to find records of cotton mill workers who had never had any schooling at all and who could not read or write. Just last month, for instance, one of my students mentioned in a class discussion that her great-grandfather (who was probably born in the 1920s) had never learned to read.

What happened? How did the South’s poor whites become so poor and uneducated?

The most common story that emerges from my white students’ family histories is something like the following: Their ancestors came from Britain to the Carolinas (or maybe Virginia or coastal Georgia) in the 18th century and were very poor. Sometime in the early-to-mid 19th century, they participated in the rural Georgia land rush and grabbed a fifty-acre plot from land that was newly opened because of the forced removal of the Creeks and Cherokees in the 1820s and 1830s. As partisan Democrats who believed in voting rights for every white man regardless of wealth, they were so devoted to Andrew Jackson that they frequently named a son after the general-turned-president or, in a few cases, after one of the lesser-known southern Democratic politicians of the time. Yet more often than not, they could not read. If they had any significant literacy skills, they were a cut above the rest of the population, and they were likely to serve as local judges or as founding members of a Methodist or Baptist church. But more often than not, my students’ ancestors were part of the general population of whites who were too poor to own slaves or to receive any formal schooling. In the year and a half that I have given this assignment to dozens of students each semester, I have never once encountered a student whose ancestors were wealthy enough to earn exemption from service in the Confederate army – that is, wealthy enough to own twenty slaves or more. And, in the vast majority of cases, my students’ families did not own a single slave.

After the Civil War – a war in which many people from these families fought for the Confederate cause – a lot of those poor white families lost their land and became sharecroppers. The loss of land usually did not happen instantaneously, but by the late 19th century, a combination of economic downturns, low cotton prices, and the lack of new land meant that there were no opportunities for the next generation of young men to strike out on their own and find a new 50-acre plot, as their grandparents had done in the age of Andrew Jackson. So, they worked for other people, probably alongside Blacks whom they likely resented. Those who could get out moved to town and became mill workers in the early 20th century. But they were no more likely to get any schooling in the mill towns than they had been in the sharecropping fields, which is why in 1940 many of these people reported to the census takers that they could not read and write and that they were earning no more than $500 a year ($9,300 in 2020 dollars).

On a few occasions, I have encountered a student whose family was moderately well-to-do before the Civil War and owned a few slaves (never more than a dozen or so), but who then lost their fortunes and even their land after the war and fell into deep poverty. But this is relatively rare and disproportionately concentrated among honors students and dual-enrolled high school students who are planning to transfer to an elite college. Most of the time, the whites in my classes who are full-time traditional UWG students come from families who went from being somewhat poor before the Civil War to being deeply impoverished a generation or two after the war. And, whether because of lack of desire, lack of opportunity, or a combination of both, at no point along the way did people in these families acquire a formal education.

After World War II, these white rural families had access to levels of education that their parents or grandparents would have never imagined. All of my students, for instance, have parents and grandparents who are perfectly literate and, in most cases, have finished high school and maybe even college. But even now, none of them are particularly well-to-do. If their parents are professionals, they are probably school teachers rather than lawyers. And many of their families still struggle. A number of student papers tell the story of recent family alcoholism or divorce or grandfathers who came back from the Vietnam War with severe mental health problems that their wives and children did not know how to address. They also tell a story of dependence on Jesus. The vast majority of my students have a grandmother – and quite likely a parent, too – who is deeply religious and has learned to trust in the Lord in the midst of hardships and family crises. Above all, the papers from my students tell the story of hard work and struggle – a struggle that, for my white students, is not that different, in many ways, from the struggle of my Black students’ families who managed to beat the odds and acquire the education to get the professional jobs that had long been denied them because of race.

Nearly all my students believe very strongly that hard work is the key to getting ahead in life, and they’re committed to the struggle. Many of them work a combination of part-time jobs for twenty, thirty, forty, or occasionally even fifty hours a week, and they often have to juggle their studies and jobs with family responsibilities that include caring for aging aunts or grandparents or babysitting the children of an older sister who got in trouble with the law for a drug violation. Sadly, the majority of these students will never finish college. Most of those who don’t will blame themselves. And if they’re like the vast majority of whites in the South – especially whites of their own social class and rural background – they will support Republican politicians who angrily oppose those who offer “special privileges” for non-white minorities.

What most of these students don’t realize is that the decisions that would determine their odds of finishing college or reaching a certain income level were made a century or more ago, and that while hard work can improve those odds, the “luck” or “chance” events that they encounter – such as health setbacks or unexpected family responsibilities – are heavily influenced by a much longer history.

What they don’t know, for instance, is that the Black students they encounter at UWG – the ones that some of their grandparents, if not their parents, might resent for being given too many “privileges” through affirmative action – are not from “average” African American families; they are from a small subset of Black families who, more than a century ago, took every opportunity they could to get as much education as they could, and who then pursued professional careers in schools or churches in the 20th century.

This striving gave them a tenuous foothold in the middle class, which the Black students at UWG are desperately trying to maintain with great effort in their own lives. If these students’ families had been white professionals, expending a similar effort, they would almost certainly not have ended up at a regional university such as UWG; they would instead have ended up at a flagship state school or a highly selective private college. But because of disparities of race and class in this country, very few Blacks ever make it to those elite colleges. Fewer than 10 percent of students at either the University of Georgia or Emory University are Black, even though these colleges are located in a state whose population is 32 percent African American. If you are a white college student in this region whose great-great grandfather was the founder of a school and whose grandparents were community leaders and pastors, you will probably have a choice of several highly selective colleges. If you are a Black student from a similar family background, you will more likely end up at a regional state university such as UWG.

The white students at UWG, by contrast, do not come from families whose ancestors made the same educational decisions. Very few of the descendants of southern large-scale plantation owners or mill superintendents end up at a regional comprehensive university such as UWG; they instead go to more selective colleges.

But that’s not what these students’ families see. They don’t see themselves as part of a less privileged group among a generally privileged race, nor do they see the Black students at the university as the product of exceptionally enterprising families who managed with great effort to partially surmount the racial injustices that have kept the vast majority of their race in much deeper poverty – and that have kept even their own professional families from receiving the same educational and wealth-building opportunities that whites in a similar position might have received.

In fact, most faculty at my institution are not even aware of this. And perhaps the reason that we’re not aware of it is because as Americans, we have a very hard time talking about social class, at least in the present and at least as far as our own circle of acquaintances is concerned. We have a vague sense that students in our institution come from poor family backgrounds, but we don’t spend a whole lot of time talking about what this means or how it relates to a century or more of history.

Large numbers of the white students in my classes really have come from families that remained illiterate for many generations, well into the twentieth century. They really did come from families that did not have the opportunity to own their own land until very recently. And they come from families that are currently in debt and facing a real struggle for economic survival.

In the midst of that, these families have developed a very strong suspicion of “elites” and “outsiders.” They have held simultaneously to a fatalism that is frequently expressed in religious language – that is, a belief that whatever happens is God’s will – and a strong commitment to meritocracy and resentment of any “special privileges” for any group. Southern evangelicalism has absorbed these values, even when their connection to the perpetuation of racial injustice is difficult to deny.

(Photo by Julie Bennett / AL.com)

Southern evangelicalism has also absorbed the value of regional and family loyalty. One of the striking things about my students’ poor white families is that they never moved away from the region, nor, as far as I have been able to tell, did they even think of moving. My students themselves, with only a few exceptions, also have no plans to move away. They come from families that have learned to support each other at any cost, since no other help is available, and as a result, leaving their family to pursue other opportunities elsewhere is unthinkable. So is supporting a political party that they identify with values that are opposed to their region. Poor southern rural whites were the very last group of white southerners to abandon the Democratic Party; as late as 1992, whites in several rural areas of Georgia supported the southern Democrat Bill Clinton over the Republican incumbent George Bush. But that changed after Clinton enacted policies of gun control, abortion rights, and gay rights in the military that directly contradicted the values of rural southern whites. Ever since 1996, the vast majority of white rural southern voters have cast their ballots for Republicans, no matter what the state of the economy is or how unpopular the incumbent Republican president might be in the rest of the country.

Both the religion and the politics of the white rural South has long been based primarily on values and regional and family loyalty. These values are deeply rooted, and they’re not likely to change after a single college course – even a course in which students are confronted with evidence from their own family history that perhaps their own wealth and educational outcomes are affected by more than luck and personal hard work. But perhaps they will see that in the midst of family values that are well worth retaining – values such as family loyalty, commitment to hard work, and caring for people in their own circle – they can also add some other values that come from knowing how earlier generations’ decisions have affected the lives of both themselves and their classmates. Their Black classmates, for instance, are the beneficiaries of families that have pursued education for generations despite the odds against them, yet their foothold on the middle class is still very tenuous because of racial disparities in wealth. And white students’ own families, while enjoying certain freedoms that come with being white (such as the freedom to carry a gun without risking a confrontation with police, a freedom that is not available in the same way to African Americans), have also found themselves severely disadvantaged in a meritocratic society that has increasingly made education – a commodity that their families have not typically valued or been able to acquire – the sine qua non for wealth acquisition and social advancement. Acquiring education without a family support network is very difficult for many people who come from historically poor white southern families – which may be one reason why in recent years the UWG retention rate for first-year white students has been even lower than its retention rate for first-year students who are Black. And if poor white students are not faring well at the nation’s colleges, is it any surprise that some have reacted against the educational meritocratic system by rejecting educational expertise entirely and denouncing a system in which they know they will never succeed?

Perhaps we need to start talking more about how disparities in education and wealth cut across class lines as well as race – and how this complex phenomenon affects not only our national politics but also the outcomes for our college students. And those of us who are evangelical Christians may have an additional reason to care about this issue, because if we are at all influenced by southern evangelicalism, we have probably absorbed, whether consciously or unconsciously, a value system that has grafted the values of poor white southern rural religion onto Christianity, whether in the form of distrust of “elite” experts or championship of a strong individualism and a firm rejection of race-based affirmative action. Paradoxically, the value system that rural southern whites and white evangelicals have adopted has predisposed them not to see or acknowledge the real problems that the white rural South faces or address their root causes. And sadly, most of those outside of evangelical circles are probably not talking enough about the real problems that low-income rural white students are facing.

Perhaps the first step in loving our neighbor in this case is to be honest about those problems and their causes, and to admit that the nation’s meritocratic system has not offered real solutions to the great-grandchildren of sharecroppers, even when (and sometimes especially when) those great-grandchildren are white.