Almost six months from publication, we’re now at the stage of trying to fix any errors in my spiritual biography of Charles Lindbergh. Most of the corrections are barely noticeable: a typo here, a misplaced comma there. But not too long ago, I caught one mistake that would have bothered me for the rest of the book’s life: I’d misidentified the version of the Bible that both Charles and Anne Lindbergh most commonly used.

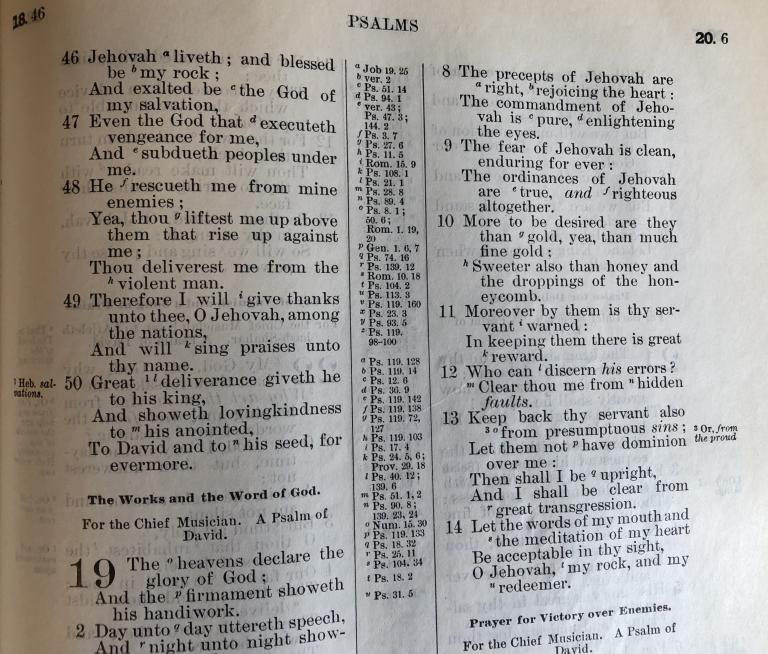

From glancing at the Bible quotations that appear in their writings, I had assumed that the Lindberghs relied on the King James Version, so I meant to make that the standard translation for the entire biography. But when the verse I had used for the dedication — one beloved of Anne Morrow Lindbergh — came back from the copy editor, I realized my mistake. For when Anne quoted Psalm 19, she didn’t celebrate that the “the firmament sheweth [God’s] handywork,” but that it “showeth his handiwork.”

Those two letters made me realize that she used a different English Bible: one common among mainline Protestants like the Presbyterian Morrows in the early 20th century, but little loved in its own time and virtually unknown in ours. Not the King James, but the American Standard Version.

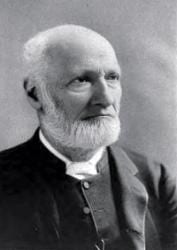

American Protestants had been revising the Authorized Version for decades. (Noah Webster’s revision came out in 1833, for example.) But the story of a “Standard” Bible for this country started back in England, when a committee gathered in June 1870 to start work on the Revised Version. The following month, they invited American scholars to collaborate on the project, with the Swiss-born theologian and church historian Philip Schaff leading the way. (I’m relying in part on Schaff biographer George Shriver for this post.) “We parted almost in tears,” he wrote when the American New Testament group concluded its work in 1880, “with mingled feelings of gladness at the completion of our work and sadness at the breaking up of our monthly meetings so full of instruction and interest and ruled by perfect harmony.” The Old Testament was completed four years later.

Schaff was convinced that the revision would be the “noblest movement of Christian union and cooperation in the nineteenth century,” but it took all his skill as a diplomat to keep the British and American committees from schism during the actual work of translation. The deal he struck was one-sided: two-thirds of the British translators had to accept any American suggestion; failing that, the U.S. group would “yield its preferences for the sake of harmony,” with their differences noted in a preface or appendix. In the end, the Americans had about 300 recommendations not accepted by their British counterparts, but when Oxford and Cambridge University Presses finally published an American edition of the Revised Version in 1898, only some of those differences were listed in the appendix.

So the American translators published their own version in 1901, calling it “standard” to distinguish it from the unofficial versions that had been circulating for twenty years. How did it diverge from the King James and Revised Versions? By less than you might think. In his history of English Bible translations, Bruce Metzger noted that the ASV substituted “Jehovah” (as Webster had done) for the Hebrew Tetragrammaton (YHWH) previously translated as “Lord” or “God,” replaced “the pit” and “hell” with the Hebrew “Sheol,” and modestly updated some of the more archaic terms and spellings from the three-century-old King James (e.g., “showeth” rather than “sheweth”).

Schaff, who died eight years before the ASV actually came out, insisted that the revision would “remain a noble monument of Christian scholarship and cooperation, which in its single devotion to Christ and to truth rises above the dividing lines of schools and sects.” But he seemed to know that it would struggle to achieve mass popularity, even among patriotic Americans who might have cherished their own nation adopting its own “standard” Bible.

Reporting on the ASV’s release in August 1901, the Washington Evening Times gently suggested that “many words and phrases are retained that might have been changed, to the advantage of the ordinary reader…” (More to the point, Metzger called it “excessively literalistic.”) Even a clergyman who thought that “nothing hitherto has approached it in actual value” warned the Times reporter that “prejudice and ignorance and bigotry will oppose and ignore” the ASV. Yet “Americans think for themselves,” he concluded, and “when they come to know and understand the beauties and the intrinsic value of this new and latest effort to present the Bible in the most perfect form attainable they will be satisfied with nothing else.”

Perhaps that was true of Protestant elites like the Morrows, and the Jehovah’s Witnesses used the ASV for several decades. But while Metzger reports that it was probably more popular in this country than the Revised Version was in the U.K., both the American and British efforts ultimately “failed to supplant the King James Version in popular favor.” Meanwhile, new rivals went even further in making biblical English sound right to 20th century ears.

A year after Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic, American scholars decided to begin work on a new English version. The project stalled during the Great Depression, but when the Revised Standard Version finally came out in 1952 (with a young Metzger as one of its contributors), Ps 19:1 closed with the more familiar phrase, “the firmament proclaims his handiwork.” (Here’s how Life magazine reported on the ballyhoo surrounding the release of the RSV.) That verse remains unchanged in the 1989 New Revised Standard Version — whose committee Metzger chaired — that the Covenant and Lutheran churches of my experience have primarily used. Though we’ll see what happens in its updated version…