I post from time to time about books that I believe tell us a lot about American religion and religious history, whether or not they can properly be counted as “religious” in their orientation. This about an author who is woefully under-studied and under-rated, namely Harry Sylvester (1908-1993), whose books tell us so much about American Catholicism, and specifically as that relates to such very contemporary issues as scandal and corruption, race and racial intolerance. The books offer a great case study in how historians can use contemporary fiction in their work.

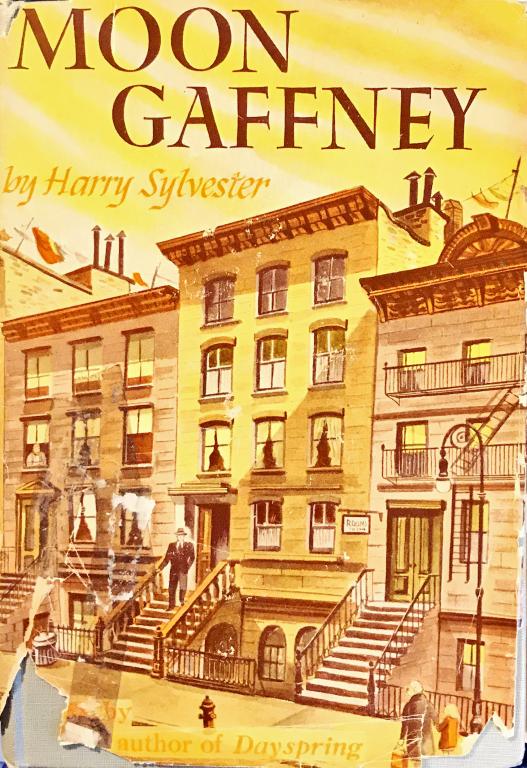

I wrote a lengthy article on Sylvester in First Things back in 2007. That led to Ignatius Press reprinting one of the novels I had discussed, namely Dayspring (1945), which is a wonderful piece about the Penitentes of New Mexico. But he also produced two other fine novels, namely Dearly Beloved (1942) and Moon Gaffney (1947), and the last of these is what I am writing about here.

Harry Sylvester had a distinguished career as a Catholic novelist, journalist and sports writer, which led to him being called a Catholic Hemingway. But during the 1940s, he moved away from the church, and his books became increasingly scathing about Catholic realities. Moon Gaffney is a novel about a young New Yorker c.1940, a time which many modern Catholics might imagine as a time of unquestioned obedience to the church and its hierarchy, an era of triumphalism and unquestioned orthodoxies. But Sylvester’s novel suggests a radically different picture. The novel portrays a running series of brushfire wars between an entrenched and often oppressive clergy and insurgent activists campaigning for social justice.

a young Manhattan Irishman with a Fordham law degree and large horizons. With luck he will soon become an Assemblyman in Albany, and perhaps in time even sit in the big chair in New York’s City Hall. He has brains, good looks, Irish wit and good Tammany connections. But he also happens to have a few “Catholic radical” acquaintances, and though far from a radical himself, he objects when a pugnacious Brooklynite damns Franklin D. Roosevelt and his “filthy Jew advisers.” One day Billy Ryan, the neighborhood Tammany boss, looks Moon straight in the eye and thunders, “You and your goddam Communist friends.” A few hours later Father Malone angrily orders Moon out of the neighborhood rectory.

The book tells how Gaffney discovers the grim political and economic realities that at their worst could be found in the city’s church establishment at this time. It represents the agonized response of a scrupulous Christian to the compromises that a powerful institution must make in order to live in the world, the recurrent struggle between the individual religious impulse, and the demands of the larger entity.

The church in Moon Gaffney, as in real life, is a substantial urban landowner, which seeks to maximize profits, yet at the same time, the demands of charity and faith require church authorities to exercise mercy towards the poor. In practice, says Sylvester, financial motives usually triumph, and the novel shows cynical church officials relying on the docility of the faithful, who dare not seek legal or journalistic assistance. They have both the temptation and the opportunity to become exploiters.

Sylvester’s sympathies at this point were firmly with the Catholic Worker movement, and the book is dedicated to a group of “good Catholic radicals.” Dorothy Day herself appears in the novel as a heroic character.

He was also deeply involved in interfaith efforts to promote Catholic-Jewish relations at a time when many working-class urban Catholics were exposed to clamorous anti-Semitic agitation, and in Sylvester’s view, the Church was doing precious little to combat this.

In Moon Gaffney, New York’s senior clergy are cynical allies of corrupt politicians and business leaders, and Church authorities act as oppressive landlords. Diocesan real estate is handled by “pietistic shysters.” At their worst, Sylvester’s clergy are anti-labor, anti-black, anti-Jewish, misogynistic, and their “terrible obscurantism” makes them willing to succumb to the demagogic appeal of Father Charles Coughlin. At their worst, he says, America has “a priesthood that lacks both charity and humility and has misled and confused its people until they mistake black for white, hate for love and darkness for light.”

Sylvester also denounced the Church’s racial insensitivity, as much as by its bias towards the rich, and he delights in showing black-white interactions that appall the more conservative characters. This is powerful stuff.

So how might a historian deal with Moon Gaffney, or use it as a resource in writing? On the plus side, it is strictly contemporary evidence in suggesting how some Catholics on the militant reforming Left viewed the hierarchy, and the conservative priesthood. However severe its critique, it is not an anti-Catholic rant, it is written from within the family circle.

If anyone ever suggests that the later criticisms that surfaced so powerfully in the 1960s or 1970s were somehow new or unprecedented, then point them to Moon Gaffney. Contrary to the myth we sometimes hear, Catholics before the 1960s – even Irish Catholics – did not view all priests as Bing Crosby or Spencer Tracy. Also remember that property deals like those depicted in the book might well have occurred as part of the Standard Operating Practice of big city business and development. We need to be alert for such acts.

Over the years, I have written a lot about the clergy abuse crisis that erupted in the US Catholic church in the 1980s, seemingly out of nowhere. Around 1980, two things changed, suddenly, to permit that explosion, namely the media’s ability and willingness to report church misdeeds, and also the church’s newfound exposure to litigation. Catholics in earlier eras – for instance in 1947 – were not naive or starry eyed about clerical failings, they just had little opportunity to read about them or explore them in any detail. Moon Gaffney takes us back to that era, and in so doing, it profoundly affects the way we study issues of abuse and misbehavior in that older world.

But at the same time, recognize that he book is an angry tract, a parti pris work, which makes zero attempt to be fair and balanced, or even moderately restrained. Obviously, no reasonable historian would present the book as a straightforward narrative, to be quoted as sober fact. For every example I might cite of a bishop of this time who fitted Sylvester’s indictment, I can find others who run flat contrary to that model. For better or worse, Moon Gaffney is a work of fiction, albeit set in a controversial current reality.

Above all, read the book for the fascinating novel it is, and discover the agony of the main character as his illusions are shattered, and he moves to a very different new political and cultural stance. And if along the way you discover something really surprising about Catholic attitudes at the time, that is splendid. But do read the book, and Sylvester’s other works.