In the stories, images, and video footage of last week’s insurrection at the Capitol, two details drew my attention. First, there was the open display of Christian nationalism. Pro-Trump activists erected a cross at the Michigan Capitol in Lansing, and they danced to Christian music (and sometimes played shofars) in Washington, D.C. As Robert P. Jones argued afterward, the “seditious mob was motivated not just by loyalty to Trump, but by an unholy amalgamation of white supremacy and Christianity that has plagued our nation since its inception and is still with us today.”

As Jones wrote, the siege on the Capitol revealed “a desperate desire by some white Christians to hang onto ownership of a diversifying country,” which relates to a second observation: that the insurrection involved open expressions of xenophobia and Sinophobia. The New York Times described, for example, how the pro-Trump mob ripped up a Chinese scroll found in the Capitol building, while a woman looked on and declared, “We don’t want Chinese bullshit.”

As a religion scholar who is also an expert on the surge in anti-Asian hate during the pandemic, I see the intersection of these forces—Christian nationalism and xenophobia—as important but underrecognized. In October, my research team at Stop AAPI Hate published a report about political candidates and their Twitter activity, and we showed that there are clear partisan patterns in who deploys inflammatory rhetoric that stigmatizes Asian people and blames them for the pandemic. Without exception, only Republican candidates have used stigmatizing terms such as “Wuhan flu” and “China virus.” Donald Trump, in particular, has been a “superspreader” of anti-Asian hate.

The politicians advancing anti-Asian hate have not only been Republican, but Christian, and scholars have begun to call attention to this fact. Most notable among them is Lucas Kwong, Assistant Professor at City Tech and the City University of New York and the author of three recent essays: one about “Sanctified Sinophobia,” another about Christian nationalism’s impact on anti-Asian hate, and a third urging Asian American Christians to take action.

Kwong also launched the Against Christian Xenophobia project, which features “An Open Letter on Anti-Asian Racism and Christian Nationalism.” In it, Kwong decries how American Christian politicians have escalated anti-Asian racism during the COVID-19 pandemic, and he encourages Christians to sign the open letter, educate themselves about the Christian nationalist politicians who have advanced racist, anti-Asian rhetoric and legislation, and learn about these politicians and their connections to churches. Ultimately, Kwong calls for these politicians and their home churches “to confess the link between racist rhetoric and racist actions, condemning both in turn.”

Over the weekend, I interviewed Prof. Kwong about his work. Here are the highlights of the interview, which I have edited lightly for length and clarity.

On the origins of the “Against Christian Xenophobia” project:

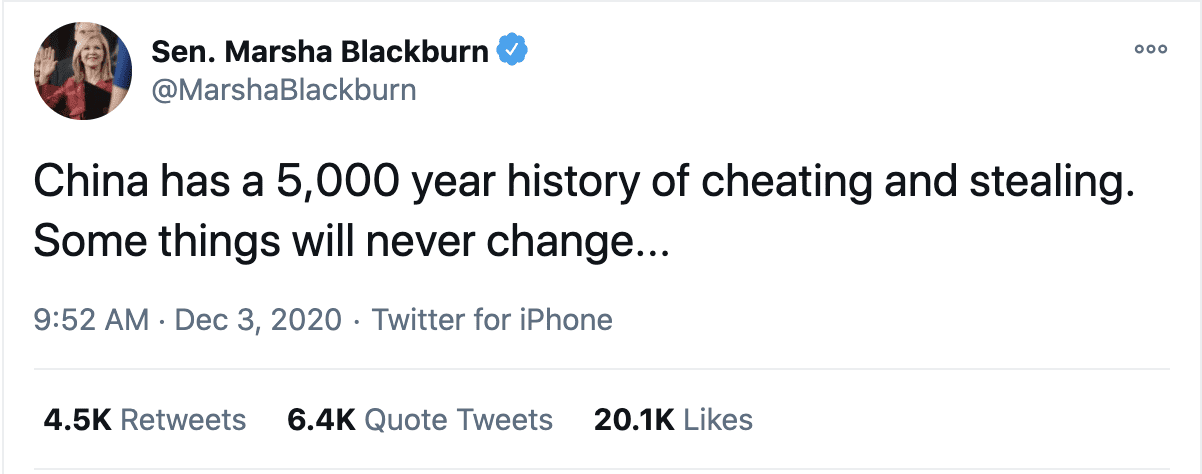

I think really the precipitating incident was Marsha Blackburn’s tweet on December 3rd, about the 5,000 years of “cheating and stealing.” …I was aware of her membership in Christ Presbyterian in Nashville and aware, as a New Yorker, that they have a pastor, Scott Sauls, that was previously at Redeemer Presbyterian, which is the church that I’m familiar with, like so many New Yorkers who attend church. So I was aware of that connection…I was writing about it, and I thought, ‘You know, I think this goes beyond Marsha Blackburn and Christ Presbyterian, I think that there is a larger pattern here,’ especially as I began to delve in and think about all the major politicians, which Stop AAPI Hate [discussed] in that very helpful report on the candidates’ rhetoric.

Almost to a person, the major drivers of this rhetoric are all outspoken, self-identified Christians. I mean, Bill Hagerty: I was shocked that he tweeted more—almost twice as many—anti-Chinese tweets as Donald Trump in the same period, and he’s a lifelong (or maybe not lifelong, but a longtime) member of an Episcopalian church, I believe, in Nashville. And the same goes for Senators Josh Hawley, Kelly Loeffler, Ted Cruz. And I felt it was very important to point out that although the rhetoric itself is harmful, it is also the legislation—which, again, Stop AAPI Hate was very helpful to direct me toward. All these people jump on the same bills. They try to get the same legislation passed. And so looking at that in light of the long history of the conjunction of Christianity and this reactionary white supremacism, frankly—which in my research I see going back to the 1890s, in a different context in Victorian Britain—I think we can very clearly see these historical patterns, that unless there is a concerted effort to dismantle material networks of power and influence, I think it will continue unabated. So that was what led me to write the letter and to adopt the strategy that I felt was important to adopt, which was to not only ask for repentance, but a clear plan for making amends.

On the deep historical roots of Christian nationalist xenophobia and Sinophobia, as expressed in Dracula and the literature of the Victorian era:

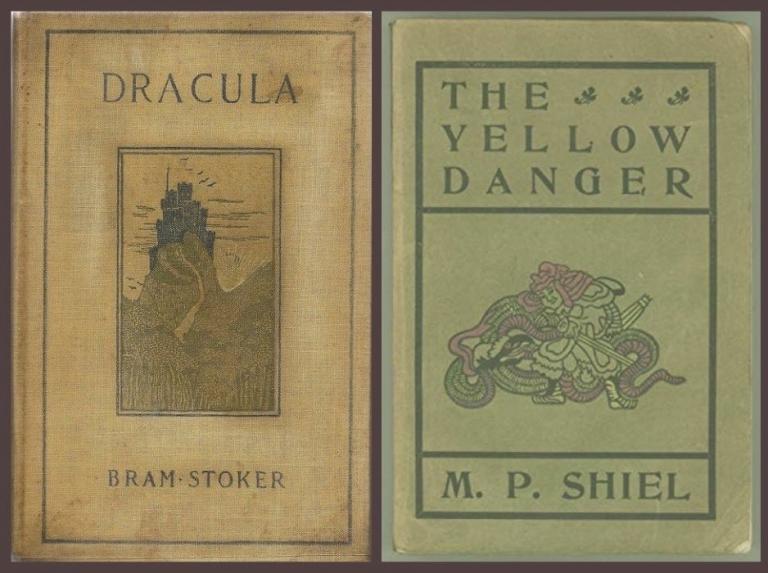

I actually wrote an article about [anti-Chinese sentiment] in Dracula. Dracula, we take for granted because it’s such a major part of the firmament of the cultural imagination, but it really was born out of the 1880s and 90s, when, much like today in the U.S., there was this obsession with the idea of imperial fall and degeneration—of biological degeneration, of political degeneration, even the degeneration of art. It was in this period that works that drew parallels between the fall of the Roman Empire and the fall of the British Empire potentially began to be published. And much like today, if you look at the alt-right and the far right, there is this obsession with Rome and with Greece and with avoiding the degeneration that befell previous great empires in the past. And so, in the 1880s and 90s, what that meant was, “What are the threats to the British Empire? What are the threats to our people, to our race?” …[There was] this fear of the East and this need to have an antagonist that was equal perhaps to the glory and the scope of the British Empire.

…What’s interesting about Dracula is, in Dracula, it’s not China per se. He is sort of on the liminal border between Europe and the Islamic world. The irony of the story is that he is a Christian soldier who fought the Turks and sort of sold his soul to the devil. He lives in Transylvania, which is figurative. In fact, in the story, Jonathan Harker says, the further east you go, the time gets stranger and less linear, and he asks at one point, “I wonder what the clocks are like in China?” So China is still the point of reference, even though they never get to China, as they move east towards Transylvania.

….Dracula sparks this flood of copies that are forgotten today, but that are trying to ape the success of Dracula. M. P. Shiel, who’s a British author, comes out with a book called The Yellow Danger, and The Yellow Danger’s central character—his name is Dr. How—is clearly modeled on Sun Yat-sen. And Dr. How is kind of this evil mastermind, much like in the vein of Dracula. He’s not literally a supernatural being, but he is of both Japanese and Chinese descent, and I think at one point it says he has both the brain of the West and the body of the East…He hatches this scheme to get the different European nations to fight against each other so that in the midst of all that bloodshed, China can rise to the top.

And strikingly, one of the first things that we learn about Dr. How is not just that he is this mastermind and this evil genius, but that he’s godless. I think it says that he has no religious emotion whatsoever. We’re meant to see that this is not just specific to his personality—this is a racial trait. That’s very much in line with [how], when the discipline of comparative religion starts in the late 19th century, race and religion are deeply intertwined…Religion is seen as being the expression of particular races, and you have this hierarchy coming from polytheism at the bottom, moving up to monotheism at the top, and each of the different religious traditions of the world are supposed to correlate to different stages of racial evolution. So when Dr. How is framed as being an atheist, that is representative of the Chinese people. It’s not an anomaly. I think it’s very much in line with the thinking at that time.

We fast forward to 2020, and we see Marsha Blackburn saying China has 5,000 years of “cheating and stealing,” and we hear, particularly this year, an explosion of the term “godless communist China.” I mean, if you just look up that term on Twitter, it is continually being refreshed. It’s not enough to call it communist China; it must be a godless communist China. Really, that trope predates communism. It predates the 1949 revolution and dovetails, of course, with the figure of the “heathen” Chinese in the 19th century.

Even though there are obviously different contexts when we’re talking about Victorian Britain versus America, I do think there is definitely a shared cultural inheritance there that has been revived today. Whether it’s conscious or subliminal, I think in these times, when there are these perceived threats to the social order, particularly to a white-dominated social order, people draw on these reflexes that are embedded in the cultural memory. And I think one of them is looking to the specter of the godless East, particularly the godless Chinese.

On the role of churches and pastors in advancing xenophobia, Sinophobia, and anti-Asian racism:

I think there are different types of relationships that any given pastor has to a candidate. On one hand, I’m thinking of Kevin McCarthy, who is from Bakersfield. He literally had his pastor—I think he’s from Valley Ridge Baptist—come in and give an opening invocation a few years ago for the first session of Congress. There you have a very explicit public identification between the pastor and the politician. Similarly, Mike Pompeo, his home church in Kansas is Eastminster [Presbyterian Church]. Its pastor, Stan Van Den Berg, went on the record in defending Mike Pompeo. So I think you have that on one hand, and then on the other hand, you have something like, for example, the relationship between Marsha Blackburn and Scott Sauls, which is that, at least publicly, there is no acknowledged relationship. The dots are all there to be connected in the public record, and anybody who cares to know will know that Marsha Blackburn is an active member of Christ Presbyterian Nashville, and Pastor Scott Saul is the head pastor of Christ Presbyterian Nashville, but there’s no open acknowledgement of that. I do believe that, despite that wide difference, what they share is the fact that having a regular church, being an active member of the church, being able to say that you are involved in a church, is central to the brand of Christian nationalist politicians.

…It is complicated insofar as Christian nationalists are not necessarily regular churchgoers, that although the most fervent Christian nationalists seem to tend to attend church regularly, a wide swath of people who profess Christian views aren’t necessarily regular churchgoers or don’t attend church. However, I do think, even though they don’t attend church, it seems central to the brand of the politicians whom they admire, that those politicians attend church and have a relationship to the church. It is beneficial to those politicians: whether or not their pastors are publicly in their corner or simply decline to issue a statement dissociating themselves from that politician, it’s in their interest to have that association.

…A lot of these pastors, they are fluent in the language of racial justice. They are fluent in the language of talking about race…Although some of them just flatly do not acknowledge the issue at all, I think a lot of them will have some sort of diversity statement on their site and in fact, will hire non-white staff pastorally and highlight that on their websites. There is clearly, on one hand, this tension between wanting to project this appearance of caring about racial justice and even writing blog posts or tweets that signal, “Hey, this is a church that cares about racial justice and cares about being welcoming to non-white Christians.” But at the same time, there is this huge elephant in the room that just goes completely unaddressed, which is that, well, one of your most prominent congregants is literally capitalizing on their affiliation with you as they pursue Sinophobic, xenophobic legislation and put that out into the mainstream and increase the risk of harm to minorities.

On how religious people must hold their churches and elected officials accountable:

On one hand, although the most fervent Christian nationalists tend to go to church, it also seems like religiosity cross-pressures Christian nationalists when it comes to their attitude toward immigrants, so that they can actually play a role in creating empathy and diminishing the influence of xenophobic rhetoric. It’s for that reason that the letter is specifically pitched—although it is welcome to allies from all backgrounds—to Asian American Christians. This is an issue in which both our faith and our ethnicity is at stake. Our race is targeted, and then our faith is exploited to launder the reputation of the people who are doing the targeting. So what I would hope is that, first for Asian Christians who are part of their communities to see that they have power…I think that there is this powerful idea of the “beloved community” that John Lewis talked about—that, in Hebrews, there is this idea of the “priesthood of all believers,” there is a radical equality that is not subtextual to the New Testament, but is right there on a quite literal level, even if you are a literalist. On that basis, I think, Christians have to go beyond making broad denunciations of racism and think, “What are the material networks of power and influence that my church is supporting, and how can I ally with other people who might not be pastors, who might not be deacons or people in positions of ‘influence,’ but how can we create a community that more accurately reflects that ‘priesthood of all believers,’ that ‘beloved community,’ in which hierarchy is replaced by an equal commitment to love and justice?”

And then I would say for non-Asian Christians, I think it’s a similar thing, but I think it’s also that some reflection is required, particularly for white evangelical Christians. I am a big believer that there are many people out there—and maybe this is optimistic—but I believe there are many people out there who simply have not connected the dots, who simply have not thought about the fact that, “Oh, I’m going to this church that, on one hand, has a diversity statement on its website, proudly features pictures of our Black, Latino, and Asian pastors or pastoral staff, and yet our most visible congregant and possibly wealthiest donor to this church is an unrepentant xenophobe or racist. I wonder what my role is, perhaps as someone who indirectly benefits from that system of mutual beneficiality? What is my role here to dismantle that relationship or to challenge it?” I really would hope that, whether you’re Asian or not, if you are a churchgoer, that [the letter] would at least prompt people to think about how sin is embodied and how it finds expression in flows of influence, power, money, and privilege, and how that intersects with racism today.