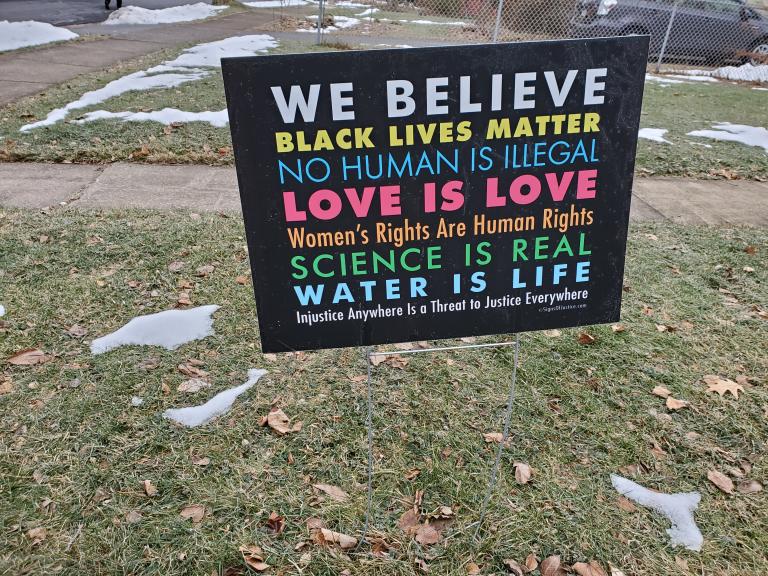

You have undoubtedly seen yard signs like this around the place.

The sentiments listed vary from the indisputable to the (in the context) somewhat controversial, but one in particular is – well, nothing like as straightforward as it looks. I know and respect what the people who put up the signs mean to say, but the raw statement that “science is real” is tendentious at best, dangerous at worst, and especially for anyone who considers themselves on the left or liberal side of things. The statement is also plain irritating. A very large body of observation and scholarship suggests just how extensively science is shaped by a variety of non-“scientific” factors and prejudices, political, cultural. and otherwise. To use a phrase that is less fashionable than was once the case, science is socially constructed. And some Science (even with an upper case S) can be real, but dead wrong.

Mask Wars

The “science is real” line originated as a song title, (from They Might Be Giants) but it has acquired a whole new partisan life in recent years over climate issues, and even more centrally during our recent debates about the coronavirus, and the related Mask Wars. A solid scientific consensus holds that wearing masks plays a major role in reducing the incidence of infection, and I wholeheartedly follow those lessons. The maxim also condemns the many weird and wonderful alternative treatments that circulated over the past few months. Did President Trump actually advocate self-medication through bleach or disinfectant? Did he recommend self-injection? Actually, no (read the Politifact analysis), but the story acquired legs to the point of becoming an urban legend. So according to this view, the science is clear, and people who go against that are deluded or dishonest. Put another way, science is as real as gravity. You might not believe in gravity, but that skepticism won’t do you much good if you step off a twenty story building.

Having said that, there were some excellent reasons why people felt dubious about that supposedly real and unequivocal science. Exhibit A would be the notorious February 2020 tweet from the US Surgeon General, Jerome M. Adams, whom it would be reasonable to assume would represent a scientific or medical consensus, and who would therefore state that authoritatively to the public. He urged,

Seriously people — STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if health care providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

Had he said “Please don’t panic buy masks, or health care workers will not have adequate supplies,” that would be one thing, but no, he said explicitly that masks did not prevent the spread of the virus, as opposed to the glorious practice of regular hand washing. Those were statements that he knew (or should have known) to be false. The accumulation of evidence from recent Asian experience left little doubt abut the role of airborne transmission, and thus the virtue of masks. Adams’s “seriously” further implies that this whole mask thing is just crazy fringe theory. As White House medical adviser Anthony Fauci proclaimed in early March, “there’s no reason to be walking around with a mask.”

And they wonder why later official government statements were met with incredulity? Or that many people decided that the science of the day was not real?

Objective Science?

The fact that an official might bend facts for political or bureaucratic convenience does not of itself contradict the “Science is real” mantra. The sense is that somewhere in the background, there is a noble figure labeled SCIENCE, a twelve foot tall gold statue clutching a sword of justice and a test tube, immune to mere worldly pressures and concerns, and single minded in the quest of truth. Her strength is as the strength of ten because her heart is pure. How sad that someone should misrepresent those objective truths for political advantage.

The problem is that science changes over time, and not just by the proper and understandable means that we know and accept. Obviously, most such change arises from the dynamic nature of the scientific process. Theoretical structures shape our views of reality until problems in them become apparent, and new ideas emerge to correct or replace those older models. The process evolves by a process of forming and testing hypotheses, commonly on the basis of new evidence as it becomes available. Scientists in 2020 believe very different things from scientists in 1920. That does not mean that the science of 1920 was necessarily wrong, or lacking in scientific validity, but just that new approaches and evidence have changed the field. Science is, and was, real.

But other parts of the story do raise questions about that imaginary twelve foot statue. There is a very large and distinguished literature on how scientific, and especially medical, statements have been shaped by biases of class, race, and (perhaps most pervasively) gender. That is an inevitable consequence of the makeup of the expert community. If white men constitute the overwhelming mass of theorists and observers, then they will not leave their prejudices at the laboratory door, but rather will import them into their work. They will present findings based on those tainted observations, which other experts will confirm because they fit the social, cultural and political paradigms of the age. Findings that fit a paradigm will be freely accepted, while deviant opinions are blocked or mocked. That holds true until the paradigms change, and the roles of mainstream and heretical are commonly reversed.

To see that process at work, look at generations of orthodox scientific findings and theorizing about women’s physical and mental ailments and well being. Or look at the literature on child sexual abuse from the 1950s through the 1970s, which utterly trivialized such behavior, mocked any concept of harmfulness, and often blamed the victims. Yet in each case, those studies purported to be founded on solid scientific methodologies, and were duly verified by subsequent researchers. As the political environment changed – as women’s voices were more heard – the science changed. The science was socially and culturally constructed.

Surely, that statement is not even close to controversial?

Eugenics: Weird Science, But (In Its Day) Science

To see how science can change and evolve, look at the theory of eugenics, which held sway over much of Western thought from the 1870s through the 1930s and beyond. Eugenics held that good or bad characteristics were passed on through heredity, and that extended to features like criminality, insanity, mental deficiency, sexual deviations, alcoholism, epilepsy, or vagrancy. All were aspects of “degeneracy” that apparently had a close connection to each other—at least they all seemed to manifest in the same degenerate blood-lines. Eugenics meant encouraging the breeding of “good” human stock, while discouraging or preventing the spread of the bad seed by means of selective breeding and sterilization. In practical terms, eugenics affected approaches to education, social welfare and criminal justice, among many other things. It also had a profound impact on religious thinkers, which is a whole other story.

The lessons of eugenics were (seemingly) confirmed by the intelligence tests that were very widely applied, and which we now understand to have been horribly flawed in conception and execution. In some versions, these notions were applied to specific races, with conclusions that mightily buttressed White Supremacy. During those long decades, just try and find credentialed scientists who actually did proclaim the biological equality of races, or who denied that Africans represented an extremely low or marginal form of humanity.

Few today would deny that eugenics was a dreadful and pernicious idea, which blighted the lives of millions. But the issue of definition is critical. Today we call it a “pseudo-science,” to stress the error of its conclusions, and the deeply unreliable methods by which the theory was established and tested. Eugenics was indeed wrong, lethally so, but in its day, it absolutely must be described, simply, as a science, precisely because it was so very widely believed to be solid and unchallengeable. To say that it was once a science does not mean that is was anything but worthless, but definitions do matter.

What Scientists Do

One criterion for establishing the scientific quality of a theory is whether it accords with what most or all scientists believe. This was a critical theme in the legal cases through the years about Creationism and Intelligent Design. Put crudely, science is what scientists do, and if they don’t do it, it ain’t science. If one or two isolated people come forward and present an opinion, then it is quite proper to object that, if they are right, why are they such an outrageous minority within the profession? Why do they account for a microscopic proportion of the published literature? They can’t really be said to be speaking for science. The same lesson emerges from the Daubert Standard by which federal courts decide whether an expert witness is presenting a scientifically valid theory. High on the list of criteria is whether the ideas are generally accepted by the scientific community.

By that standard, eugenics between (say) 1870 and 1940 was unquestionably a science because it reflected the views of such a scientific consensus. That is not to say that every single scientist accepted its approaches, but those critics were marginalized and treated as isolated cranks. What makes a pseudo-science is not the accuracy or reliability or its conclusions, but simply its status within the intellectual world. If it commands an overwhelming majority, it’s science. If not, not. Eugenics in its day was thus a science. In the same way, alchemy in the sixteenth century clearly occupied the status of science, or indeed Science, although today it would just as obviously be in the status of “pseudo.”

So why should we not speak of a bygone world-view as “pseudo-science”? If we are to say that older ideas must be “pseudo-science” because we now know them to be incorrect and flawed, then the scientific statements of all previous generations must be so labeled. That also means that by 2050, say, our present scientific knowledge will have been so surpassed and revised that the intellectual world of 2021 must constitute pseudo-science.

Most important, to speak of some prevailing idea as “pseudo-science” suggests that it must be a violation of the proper mainstream order which carries on existing somewhere like an exiled prince or prophet, so that during the long supremacy of eugenics or alchemy, True Science was lurking somewhere, constantly protesting. Or that all the “real” scientists were loudly wailing and gnashing their test tubes over all the bad things being perpetrated in their name. Or, indeed, that a twelve foot gold statue was desperately and prophetically crying her protests against the global tyranny of error. But no, no cries were heard, because that metaphysical True Science didn’t exist. Eugenics and scientific racism were the Science of the day, and the world paid a brutally heavy price for that fact.

Part of the nature of science is that it always changes and develops. You may like the consensus on any given issue as it stands right now, but don’t assume that it will stick there. It won’t. In consequence, it’s perilous to idealize Science as a rhetorical weapon against political or cultural rivals.

So is Science real? Sure. Well, sort of. But it cannot fail to be shaped and reshaped by the assumptions of the world in which it operates, and of the shifting interest groups within that world.