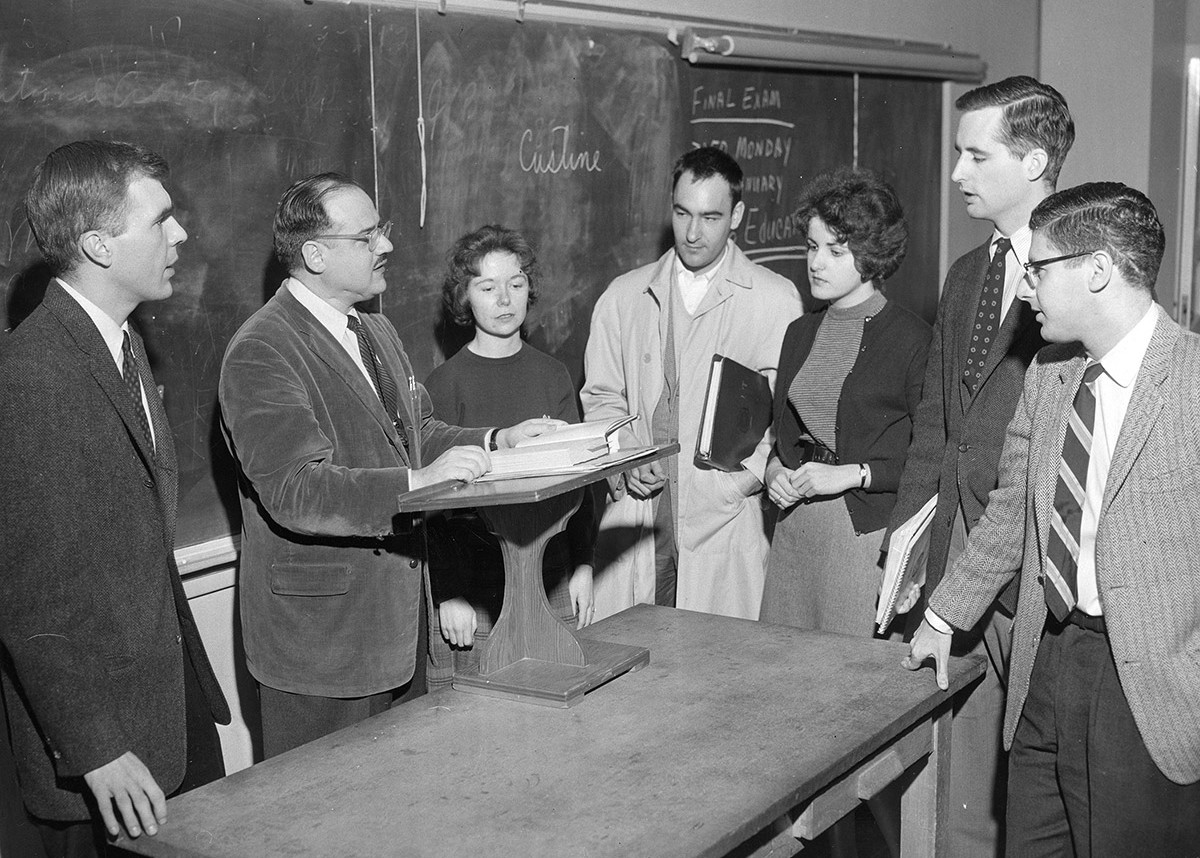

My Ph.D. dissertation advisor taught at Brown University for thirty-three years. Two of the other professors for whom I TA’ed in my graduate years were probably at Brown for even longer. And some of the younger faculty, who had been at Brown for only a few years when I arrived at the university in 1999, are still there more than two decades later, and will almost certainly stay until their retirement.

This, of course, is not unique to Brown, and among academics, it’s hardly noteworthy. At my current university, the older faculty members in our department have been there for more than twenty years, and nearly all of them are still in the same office spaces that they occupied when I first arrived. That’s how academia works these days, especially in the humanities.

In the 1960s, when the academic job market was thriving and there were more assistant professorships than newly minted PhDs, it was not uncommon for an ambitious young faculty member who published quickly to move from one tenure-track job to another in short order. But for the last half-century, there has been stiff competition for nearly every tenure-track position in the humanities, and once people land a job, they’re as likely as not to stay for life, no matter how much they publish. That is especially true at this particular moment, when universities are cutting academic programs and there are hardly any new positions in the humanities available.

The weak academic job market has created a rhythm of life for tenured professors that is radically out of step with most of the rest of the American workforce. The average American worker might change jobs once every four or five years, according to statistics compiled by the US Department of Labor. For a highly educated professional to move to a new town to take a job in their late 20s and never leave for the next forty years is not the way that the modern American workforce usually functions. For a highly educated professional to take this job and find that they cannot leave (at least if they want to stay in the same line of work) is even more unusual.

The tenure system, which has artificially constricted the number of jobs, can be both a blessing and a curse for those prone to wanderlust. On the one hand, for those who receive it, tenure provides a near-guarantee of job security in all but the most exceptional of situations, and it prevents younger scholars from ever displacing a professor until he or she is ready to retire. But on the other hand, by making the cost of hiring a tenured professor enormously expensive – far more expensive, in fact, than a perfectly free labor market would allow – it guarantees that there will be hardly any job openings for professors of higher rank. Nearly all job openings are for adjuncts, lecturers, or assistant professors; senior professors are unlikely to ever have an opportunity to move to another university unless they go into administration or are perhaps one of only about a half-dozen or so of the most exceptional scholars in their field. The rest can expect to stay where they are until they retire. And while they theoretically could get a job outside academia, most who investigate this route discover that to become a viable job candidate in the non-academic world, they will have to invest in months or even years of retooling.

Some professors react to unexpected lack of job mobility by becoming frustrated and depressed. I have encountered a number of those over the years. Even professors at top Ivy League schools have sometimes expressed irritation that they couldn’t leave to take a job elsewhere. And if even Harvard professors are not immune from feeling trapped, it’s hardly surprising that professors at other colleges and universities wonder at times what they have gotten themselves into when it dawns on them that they will never be able to leave their current academic department until retirement.

I think that what makes the lack of job mobility particularly hard for some academics to handle is that it cuts against the grain of all the habits they have acquired up to that point in their lives. Most academics (myself included) moved around a lot before acquiring their first tenure-track job. They likely chose to attend a selective college away from home. They may have studied abroad, lived briefly in another country, or spent a summer or two in a major city pursuing a competitive internship. Graduate school often involved a frenzy of travel as well. Most likely, they attended grad school in a large city or academically minded college town, and they supplemented their studies with research travel that may have taken them to another continent or, at the very least, across the United States. Perhaps they concluded their Ph.D. work with a visiting assistant professorship or a postdoc at yet another university. By the time they finally settled into a long-term teaching position, they had almost certainly spent more than a decade moving from city to city, traveling much of the United States or the world, and surrounding themselves with the intellectual stimulation of some of the most prestigious academic centers.

But the rest of their life will not be like that. Instead, in nearly every case, the newly minted humanities Ph.D. who is fortunate to land a tenure-track job (and this, of course, is now a very small minority) will spend the rest of his or her professional life in the same place, walking the same campus and working with the same colleagues for decade after decade. For most, this job will not be in a major city or academic center. It might not even be in a state that the newly minted Ph.D. ever envisioned living in.

For a lot of millennial and Gen-X professionals, the excitement of living in a large urban area, with easy access to high-end theatrical performances, music concerts, and trendy bars is both an expectation and a status symbol. It can therefore come as a shock to some humanities PhDs when they realize at the end of their graduate careers that if they want to teach college courses, they will never again have access to that life. In my last year of graduate school, when I accepted a tenure-track job at the University of West Georgia, one of my colleagues in the program was skeptical about the idea of working at such a place in the semi-rural South, a full hour away from the nearest major city. “I’m not sure that I could live anywhere where I can’t get home delivery of the New York Times,” he told me. The next year he accepted a teaching position at a branch campus of the University of Mississippi, which is where he still is today, fifteen years later.

But my friend found out that he could actually be very happy in a place that he had never envisioned living. He learned to teach Mississippi history and found that he actually enjoyed it. He found that he appreciated conversations with his students, even though their religious and political views were often wildly divergent from his own. And he liked the weather, at least partly. After years of college and grad school in the snowy Northeast, the chance to wear shorts in November had a certain attraction.

Most academics make a similar transition in their thinking or else they become frustrated people, increasingly prone to depression and musings about what might have been if only they had been able to leave. They either become unbearable to themselves and everyone around them in their frustration over their perceived entrapment or they accept the permanence of their surroundings as a source of joy (however unexpected) and communicate that delight to others.

As a Christian, I believe that the permanence of an academic job can be a source of sanctification. I confess that for years, I did not instinctively embrace my lack of job mobility as a blessing, even though my Christian theological beliefs suggested that I should. I valued having control over my life. I wanted to be able to move onto bigger and better things, as I perceived them, especially when there was unpleasantness in my department, but oftentimes even when there wasn’t. It was a shock for me to realize that I could never write my way out of West Georgia. The academic jobs that I was looking for simply weren’t there, no matter how much I published, and if I wanted to continue teaching college history classes, I would in all probability never leave.

After years of fighting against this reality and grumbling about the situation that I was in, I realized that God had used the reality of the early 21st-century academic job market to teach me some important spiritual lessons. One was humility; I have realized that I can’t simply send off my C.V. and expect to get a different job, since my skills are not in high demand. A second lesson was to trust God; it is God who has planned my steps and gives me my daily bread – not my own intellectual resources. The fact that I have a tenured teaching job at all is a gift of God that many recent PhDs have not been given. It is not something that I deserve, and it’s not something that I can boast about as the product of my own achievement.

And finally, the inability to leave the community that I am in has forced me to learn to live with people over the long term in a way that is perhaps largely lost in our modern society. In most centuries in human history, people lived with one particular social group for their entire lives. It was only in the last two centuries – and especially in the last half century or so – that for educated professionals at least, this became the exception rather than the rule. Today most professionals can leave a community, whether it be a job, a neighborhood, a state, a church, or even a family, whenever the situation becomes too frustrating. I think we all know many people who have. A few years ago, I was sitting on a plane and heard two young professionals talking to each other about the need to confront frustrating employment situations by pulling up stakes and moving on. “Steve Jobs said that if you hate your job, wait six months, and if you still feel the same way, leave,” he said. Life is too short to stick with a job you hate, he thought. And in the world of computer programming or other tech fields, that might be possible. When I lived for a summer in the Washington, DC, area in the late 1990s, I was surrounded by software developers who could decide in the morning that they wanted to work for a different company and by that afternoon start fielding job offers. But humanities professors cannot leave. And so, over the course of years, they gradually learn what people in small communities have known for millennia: the art of working alongside the same people for decades – people who can get on one’s nerves but who, over a long period of time, one might come to deeply respect, even through disagreements. After all, it’s not easy to work with the same dozen people or so in the same department for year after year after year.

I’m still learning those lessons, and I won’t pretend that I don’t find this life stifling at times. My wife (Nadya), a fellow history professor who moved around even more often than I did in her early life, has handled this unexpected lack of mobility with a lot more gratitude most of the time. But I have also come to respect and appreciate other people in a way that I don’t think I did when I first arrived. I have learned to empathize with them a bit more and to admire their selfless contributions to our students and our program, which often go far beyond what I might have imagined and what I myself am doing. And I have realized how selfishly ambitious I have been in my desire to leave others behind and surround myself with constant change and more intellectual excitement. The life that God has called most people to in the history of the world is a life not of constant change or frequent mobility, but the life of community – a community made up not of the people of our own choosing but of the people that God has called us to serve and to serve alongside.

An academic community – especially a secular one – may seem to be an odd place to learn that lesson. But sometimes God takes the unexpected things of the secular world to teach Christians a profound spiritual truth.