To my non-expert ears, one of the most persistent themes sounding in American religious history is that of Americans wishing their country were more religious.

Nowadays, that concern usually attaches to the much-discussed rise of the “religious nones.” When the General Social Survey began in 1972, just 5% of its respondents identified with no religion. But as political scientist Ryan Burge notes, that number has skyrocketed since reaching double digits a quarter-century ago, doubling from 12% in 1996 to 24% in 2018. By many measures, such non-affiliation — and disaffiliation — is even more common among younger Americans. In 2019, the Pew Research Center reported that 40% of millennials were religiously unaffiliated, a 10-point rise in just ten years. The 49% of the same age group identifying as Christians was down 16 points over the same decade.

Burge’s also a Baptist pastor, and his work on “the nones” — including a short book by that title published today — is inspired by the same motivation that led me to write a “spiritual but not religious” biography of one famous American: to help fellow Christians understand their friends, relatives, neighbors, and colleagues who are neither disbelievers nor adherents, but something more complicated and less familiar. But researching my book on Charles Lindbergh also reminded me that we don’t have to look too far back in American history to find similar anxieties about religious belonging, behavior, and belief.

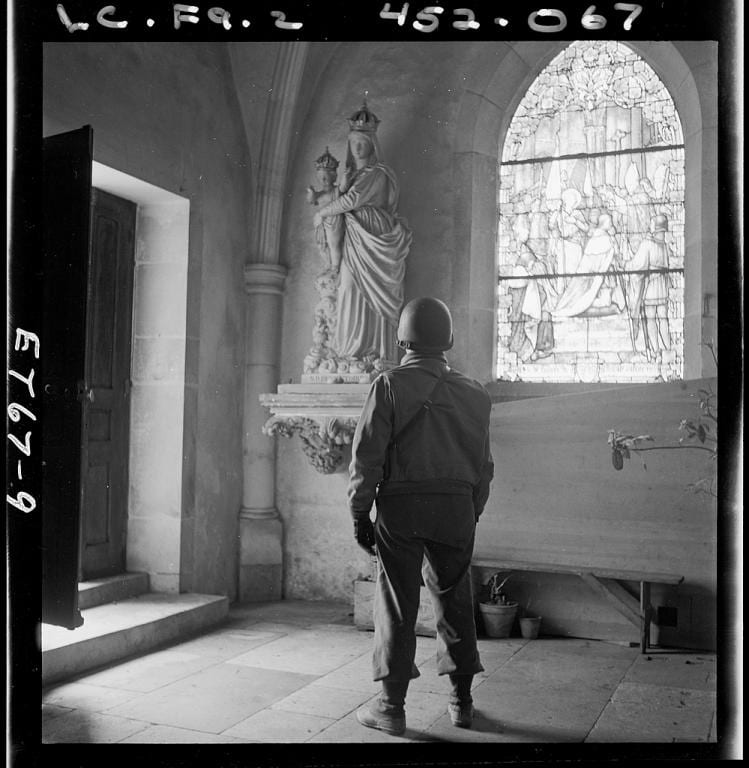

In fact, the fear used to be far greater. In the waning days of World War II, for example, one Catholic priest claimed that 70% of Americans were religious “nones.”

Without citing any source for his numbers, Father James Keller warned readers of the May 1945 issue of the American Ecclesiastical Review that there were

approximately 100,000,000 individuals in our country who are living off the benefits of Christianity, but who are becoming less and less conscious of the great Christian fundamentals that make possible their present way of life…. If this trend goes far enough, many believe that it will open the way for the speedy rise of a new paganism that would eventually remove the United States from the society of Christian nations.

Trusting that everyone had “a bit of the missionary” in them, Keller hoped to recruit a movement he called The Christophers: “bearers of Christ” who would work in areas like education, communications, government, and the labor movement “to bring Christ to all in our land—whether they be in the crowded cities or in the most remote and sparsely settled areas—who either do not know Christ or are opposed to Him.” A follow-up article in 1946 called for a million such lay workers, describing the end of WWII and the start of the Cold War as “the most unusual opportunity in history to recapture the world for Christ.”

In a sense, Keller was simply extending the philosophy of his religious order. Maryknoll had been founded in 1911 by Fathers Thomas Price and James Walsh, who appealed for “young men who feel a strong desire to toil for the souls of heathen people and who are willing to go afar with no hope of earthly recompense and with no guarantee of a return to their native land…” But rather than toiling for Asian souls in Maryknoll’s traditional fields, Keller would spend his career in his native land. (In fact, he rejected a foreign assignment in 1946 in order to focus on building his Christophers organization.)

The Catholic Church had long regarded the U.S. as a missions field, sending clergy to help faithful immigrants resist assimilation into a Protestant culture. But Keller was influenced by “Americanists” like the historian Peter Guilday, who envisioned American Catholics “naturally and integrally” intertwining their spiritual and national allegiances. To his successor and biographer, Richard Armstrong, Keller’s 1945 letter just repeated “the old Americanist theme in modern garb.” Though that article would be reprinted and distributed by bishops around the county, the priest emphasized broadly Christian fundamentals (“the concept of a personal God, the divinity of Christ, the Ten Commandments, the sacredness of the individual, and the sanctity of marriage and the home”) rather than Catholic dogmas, and the work of the Christophers would fit the broadly “Judeo-Christian” orientation of Eisenhower-era civil religion. (I first encountered Keller via a letter from him in the papers of the secular Jewish filmmaker Billy Wilder, who received a Christopher award for his adaptation of Charles Lindbergh’s book, The Spirit of St. Louis.)

Though the patriotic Keller fretted about the infiltration of Communism into American universities, newspapers, and labor unions, he insisted that most of his “Hundred Million” were “certainly neither anti-religious nor atheistic.” Their American values were Christian values, threatened by “savage forces” bent on stamping out the religion that served as “the one great universal cause that champions the dignity of the human being.” So Keller pronounced himself “very hopeful” that the “trend has not developed to the degree that it is incapable of remedy.”

(That, too, rings familiar. In previewing his book last month in Christianity Today, Burge pointed to research showing that “nones” are as likely to become Christians as atheists or agnostics, and he quoted Ed Stetzer’s maxim that “The unaffiliated aren’t the unreachable.”)

Keller wildly overstated the degree of religious non-affiliation in 1945, but his optimism was not unfounded: the years following World War II proved to be a time of significant religious ferment in the United States. The same month that Keller published his “Hundred Million” article, seventy thousand Chicagoans crammed into Soldier Field for a Youth for Christ rally, where the roster of speakers included a young evangelist named Billy Graham. Four years later, Graham appealed to some of the same anti-Communist themes as Keller in his landmark revival in Los Angeles. In between those milestones in the postwar emergence of neo-evangelicalism, religious historian Patrick Allitt also notes phenomena as disparate as the growing popularity of clergy who made use of psychoanalysis (Protestant pastor Norman Vincent Peale and Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman) and the mini-surge of young men eager to follow Thomas Merton into monasticism after the publication of The Seven Storey Mountain in 1948.

That was the same year that Charles Lindbergh published his own appeal for Western civilization to recover religious wisdom, Of Flight and Life, and Father Keller wrote his most popular book, You Can Change the World. The latter inspired a short Hollywood film starring Bob Hope, Jack Benny, and Loretta Young and a weekly Christophers TV series, though its reach paled next to that of Fulton J. Sheen, who used mass media to bring Catholicism to the American masses.

Twelve years after Keller’s initial article, the Census Bureau found a new significance for his 100 million number: that’s how many American adults identfied as Protestant or Catholic in 1957. That year, only 4% of respondents to a bureau poll claimed no religious affiliation, similar to the GSS figure fifteen years later.

None of which is to say that today’s concern about religious non-affiliation will certainly give way to tomorrow’s religious revival. At this blog and in a recent book, Philip has persuasively argued that demographic changes alone are pushing American society towards something more like European-style secularization. But the story of Father Keller’s “Hundred Million” does remind me that there’s nothing new under the sun… and that history has a way of providing events like wars — and pandemics — to disrupt outcomes that seem inevitable.

Armstrong’s biography of Keller seems to be out of print. But Keller’s 1963 autobiography, To Light a Candle, is available online.