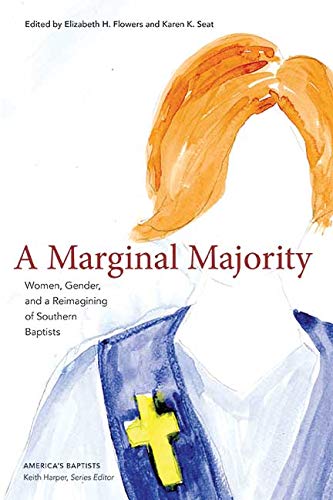

Today is a guest post. My Baylor colleague Elizabeth Flowers has a new co-edited collection of essays (with Karen K. Seat) entitled A Marginal Majority: Women, Gender, and a Reimagining of Southern Baptists (University of Tennessee Press, 2020). As that speaks to many current concerns in American religion, I have invited the two to describe the book and its arguments.

A Marginal Majority

It would be an understatement to claim that the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) has a complicated past regarding women and matters of gender. Determining exactly what women’s roles in home, church and society ought to be, or what those roles should be called, has long been a contentious subject (and as seen with Beth Moore, a bit of a recent public relations problem). For nearly a decade now, a dozen women scholars, ourselves included, have met, “fellowshipped” (a good Baptist word!), conversed, and wondered how to tell a different and more nuanced story of the SBC’s past, one that might better help us grasp the present moment. A Marginal Majority is the professional result of our collaboration.

Intended for laypersons and scholars alike, our study explores both the history of Southern Baptist women and how that history reshapes our understanding of the denomination and its contemporary debates, including #Metoo, third-wave feminism, and critical race theory. By highlighting women, the majority of the SBC in sheer numbers, ours is a corrective to the long-standing claim of the Southern Baptist historian Leon McBeth, who only half-jokingly chided his male peers: “If any of you men want to get away from women, here is one way you can do it: just get into the pages of Baptist history. Women will not bother you there.”

A Marginal Majority is comprehensive. It starts with women as SBC fund-raisers and the force behind the Cooperative Program and quickly moves to the ways they drove denominational growth through missions, whether that be as missionaries, graduates of the Woman’s Missionary Union’s Training School, or participants in their local mission societies and circles. But while the Woman’s Missionary Union is a major player in the first few chapters, by the time the volume reaches the mid-twentieth century, the historic women’s organization drops out of the narrative. Later chapters consider women’s attendance at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and debates over civil rights, second-wave feminism, the Equal Rights Amendment, women’s ordination, and sexual identity. Conservative women play a role too as the volume explores the emergence of their teaching ministries and theologies of women’s submission and gender complementarianism.

Along the way, A Marginal Majority introduces new personalities, such as Jewell Legett, the frontier girl who eventually followed her “heroine,” Lottie Moon, to China. It offers fresh considerations of familiar figures, such as first lady Rosalynn Carter, who sought a new “Southern strategy” to feminist issues, or of the fraught relationship between Annie Armstrong and Nannie Helen Burroughs. One chapter follows the twists and turns of Beth Moore’s Twitter feed, predicting recent events. And how many Baptist professors out there know that the novels of Isla Mae Mullins perhaps outsold the theological tomes of her seminary-president husband, E. Y. Mullins? Indeed, she penned a best-selling series designed to “teach” white Southern women how to “Christianize and civilize” their domestic help by working to instill within African Americans the values and loyalties of the “Old South.”

That chapter joins several others to probe the power dynamics of race and class as the SBC came to dominate the Jim Crow South and grew into a national behemoth. Additionally, the collection provides insights into why the denomination politically aligned with the Christian right in the last decades of the twentieth century and the consequences of that move.

Contributors sometimes take the theme of “reimagining” in different directions and come to varied conclusions. Of course, Southern Baptist women never spoke in any one voice. Progressive impulses competed with conservative ones. Attempts at change occasionally emerged but were often hindered by a desire to maintain the status quo. Thus, while some of the earlier essays highlight women moving toward greater spheres of influence, read together, the chapters tell a somber story of women’s increasing marginalization. In fact, as we gathered and arranged the essays into a chronologically structured volume, we quickly recognized that ours was a declension narrative. Not only did the denomination become more oriented toward authoritarianism as it clamped down on evangelical feminism, but as several chapters reveal, even as Southern Baptist women sought agency, they often took it from others. These topics resonated as we worked on the book during the politics of Trump, #ChurchToo, and Black Lives Matter.

In its reimagining, A Marginal Majority does point to new possibilities in writing denominational history. Despite the turn away from denominations in American religious history, they are crucial to understanding the past. Millions of Americans, and women especially, have organized their lives and social networks according to the denominational identities that inform their local churches and congregations. And even though denominational numbers have steadily declined, more Christians in the US worship in denominationally-related congregations than not.

Most of the contributors share a Southern Baptist heritage. We know the SBC world personally as well as from our research. To our minds, there is an honesty and transparency in the chapters as they contradict the triumphalism of the past and negotiate that insider-outsider status. Several indicate books that are either in the making or recently published. See, for instance, over the past year: Laine Scales and Melody Maxwell, Doing the Word: Southern Baptists’ Carver School of Church Social Work and Its Predecessors, 1907-1997; Carol Holcomb, Home Without Walls: Southern Baptist Women and Social Reform in the Progressive Era; and Courtney Pace, Freedom Faith: The Womanist Vision of Prathia Hall. Each of us are in the midst of monographs. One (Flowers) is a cultural history of inerrancy that foregrounds women, gender and race; and the other (Seat) considers the relationship between Southern Baptist patriarchy and the free-market economy.

If comprehensive, A Marginal Majority is hardly exhaustive. There remain, of course, historical absences, missing voices, and neglected events. This reimagining, then, invites other scholars to join us in the margins of history, where women will indeed bother you. And perhaps, as recent days have demonstrated, the needling just might be intentional.

LIST OF CHAPTERS

“A Greater Influence Than You Imagine”: Women Lead the Way to Southern Baptist Centralization, by C. Delane Tew

“I Can’t Go In Alone”: A Frontier Girl’s Transformation into a Southern Baptist Missionary, by T. Laine Scales, Chelsea L. Cichocki, and Kari S. Rood

“The Mammy Sues Are Scarce in the South Now”: Southern Baptist Women, Domestic Workers, and Progressive Era Racial Uplift, by Joanna Lile

Saving Souls and Society: The WMU and Social Reform in the Progressive Era, by Carol Crawford Holcomb

Making a Home in the New “House Beautiful”: The Woman’s Missionary Union Training School Negotiates Change and Decline, 1942–1963, by T. Laine Scales

“A Christian Attitude toward Other Races”: Southern Baptist Women and Race Relations, 1945–1965, by Melody Maxwell

“I’M FOR ERA”: Faith, Feminism, and the “Southern Strategy” of a Southern Baptist First Lady, by Elizabeth H. Flowers

Camelot Revisited: Women Doctoral Graduates of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1982–1992, Talk about the Seminary and Their Lives since SBTS . . . Again, by Susan M. Shaw, Kryn Freehling-Burton, O’Dessa Monnier, and Tisa Lewis

From Molly Marshall to Sarah Palin: Southern Baptist Gender Battles and the Politics of Complementarianism, by Karen K. Seat

“My Husband Wears the Cowboy Boots in Our Family”: The Preacherly Paradox of Beth Moore, by Courtney Pace