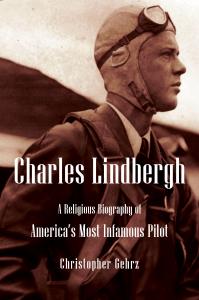

We’re now four months away from the publication of Charles Lindbergh: A Religious Biography of America’s Most Infamous Pilot. So today I thought I’d share an outtake from the book: my first try at writing its first page. While only fragments of what I wrote survived into the final manuscript, I think the attempt points to some interesting aspects of the book.

Just be sure to read to the end. If you don’t, you’ll completely miss the point.

At first, no one noticed him slip through the folds of the tent and step onto the sawdust-covered floor. Now 47 years old, the man his friends once called Slim had started to grow paunchy; his boyishly blond hair was fading to gray and thinning. In Los Angeles for airline business, that Sunday morning had — as usual — not found him in church. Yet in the afternoon he found himself walking downtown, to the corner of Washington and Hill. As he lingered in the back, he wasn’t even sure what brought him there. Slim told himself he was simply curious: the so-called “crusade” had been all over the Hearst newspapers. (Hearst: the same man who had once offered him half a million dollars to star in his own biopic.) Perhaps he just wanted to be anonymous for once: not the most famous man in the world, but just one of six thousand faces turned towards the stage, where Billy Graham was preaching on Psalm 2: “Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?”

Fire and brimstone weren’t to the newcomer’s taste. Words like “iniquity” and “repentance” made Slim feel like a child again, sitting in gray flannel in the front pew of a small town church, a political prop for his father’s congressional campaign. But as the sermon turned to current events, he perked up. “Russia has the bomb,” warned Graham, “and judgment is just around the corner unless we have a revival and listen to God the Holy Ghost!” True enough, a week before, Pres. Truman had admitted that the Soviet Union had successfully tested its own atomic weapon. And just that morning, headlines announced that Mao and his Communists had taken power in China. Slim knew that his old warnings were being proven true: the real threat was Stalin after all.

He listened more attentively, tuning out the whispers of recognition from a few of his neighbors — ignoring the accusing glances from a few more. “Judgment is coming,” Graham continued. “We’re no better than Sodom and Gomorrah. We don’t deserve to be spared any more than they were.” But the message didn’t sink in until the preacher turned his sights on other threats:

Scientists pretending that they had all the answers. Slim nodded gravely. Political parties doing the same. He nodded again. Marriages going cold and spouses threatening divorce. And now tears welled up in the weathered corners of his blue eyes.

“We’ll never have peace,” concluded Graham, “until we have Jesus in our hearts… Do you want to know Christ?”

Before he knew it, Slim was raising his hand and walking down the main aisle.

And so, on October 2, 1949, Charles A. Lindbergh made a decision for Christ.

Only he didn’t.

As far as I know, Charles Lindbergh never attended a Billy Graham crusade, let alone the one in Los Angeles that made the evangelist as famous as Lindbergh and resulted in the conversions of celebrities like radio host Stuart Hamblen, gangster Jim Vaus, and runner Louis Zamperini, who had competed in the same Olympics that Lindbergh attended as Hermann Göring’s guest. And, in any case, Lindbergh never converted to Christianity. So why would I consider starting a biography of Charles Lindbergh with something that never happened in the life of Charles Lindbergh?

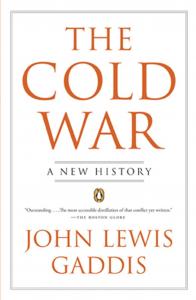

First, as a tribute to one of my doctoral advisors. In his 2005 history of The Cold War, John Gaddis began the second chapter with a harrowing account of the Korean War escalating to the point of nuclear weapons being dropped everywhere from Vladivostok to Hamburg. “[A]nd so, to paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, it might have gone,” John concluded, then started a new paragraph: “But it didn’t.”

First, as a tribute to one of my doctoral advisors. In his 2005 history of The Cold War, John Gaddis began the second chapter with a harrowing account of the Korean War escalating to the point of nuclear weapons being dropped everywhere from Vladivostok to Hamburg. “[A]nd so, to paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, it might have gone,” John concluded, then started a new paragraph: “But it didn’t.”

It’s my favorite example of John’s affinity for counterfactual analysis, which he discussed in one of the Oxford lectures published in 2004 as The Landscape of History. If it sounds foolish to imagine how the past “might have gone,” remember that history is a science whose researchers always conduct thought experiments in the laboratories of their own imaginations. And to understand what did happen, we sometimes need to contemplate what might have happened: it helps us discern causes and effects, and underscores the contingent nature of history.

So if we start by considering how Charles Lindbergh might have converted to Christianity, we might start to understand better why he didn’t.

I do think Lindbergh went through a kind of spiritual conversion, about five years before Graham’s crusade in Los Angeles. In fact, that’s where I ended up starting my book: with Lindbergh buying a copy of the New Testament just before deploying to the South Pacific, where he secretly flew fifty combat missions and shot down one Japanese plane. His experience of World War II did deepen Lindbergh’s antipathy to Soviet atheism and Western materialism alike. It did make him rethink a youthful faith in scientific inquiry guiding technological progress. It did disabuse him of most utopian ambitions of early aviation. And it did coincide with his first intensive reading of the Christian Bible, with the result that Jesus was the most-quoted figure in the short book Lindbergh published the year before Graham’s crusade, Of Flight and Life.

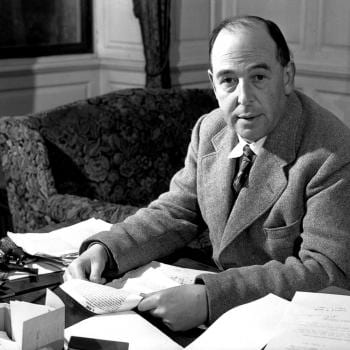

It didn’t make Lindbergh a Christian. He admired Jesus as nothing less or more than the “great moral teacher” that C.S. Lewis had just argued was impossible, since Jesus’ claims of divinity made him either a lunatic, liar, or Lord.

By the time he published The Spirit of St. Louis in 1953, Lindbergh had decided that it was impossible to remain an agnostic, let alone an atheist. But the God he described in an article a year later was intangible and incomprehensible, detached and disinterested in human choices. “There is a vast difference in knowing there is a God,” exclaimed one dismayed evangelical reader, “and having a personal relationship with him through faith in Jesus Christ.”

The only intense personal relationships Lindbergh began in the late 1950s were his secret affairs with three German women. But that disgruntled Christian’s letter reminds me of the final reason I thought about starting with the fiction of Lindbergh making a decision for Christ: it’s the twist most Christian readers expect to happen at some point in a biography written by a Christian writer and published by a Christian publisher.

The only intense personal relationships Lindbergh began in the late 1950s were his secret affairs with three German women. But that disgruntled Christian’s letter reminds me of the final reason I thought about starting with the fiction of Lindbergh making a decision for Christ: it’s the twist most Christian readers expect to happen at some point in a biography written by a Christian writer and published by a Christian publisher.

Actually, I’ll go farther: it’s the twist that they want to have happened. In a year when rates of religious adherence in America have fallen to historic lows and churches are rethinking their outreach to “religious nones,” I wonder if Christian readers will feel a bit deflated to read the story of a spiritual seeker who reads the Bible, befriends Christians, and yet never embraces their religion.

That’s how I feel, most days. Would that Charles Lindbergh had had the humility to engage in the repentance that Billy Graham took to be the precondition for a Christian conversion. Would that he had experienced the Bible not just as a collection of wise sayings but as “an altar where we meet the living Lord.” The cynic in me suspects that a Lindbergh who converted to post-WWII American evangelicalism would as likely had his most troubling views deepened as disrupted. But at my more hopeful, I also believe, with the theologian Don Frisk, that being “converted to Christ is always in a sense to be converted (turned) to the world… to see the world through the eyes of Christ,” in whom there is no Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female.

So his life might have gone. But it didn’t. That’s not the story I’m given to tell.

But the fact that my book doesn’t include a page like the one I drafted is itself significant, revealing a great deal about our subject — and perhaps ourselves.