Last week it was reported that Howard University, one of the United States’ most prestigious historically black universities, intends to close its Department of Classics. So today I’m happy to welcome to The Anxious Bench Dr. Anika T. Prather, a Howard alum who has taught classics at her alma mater and is the founder of a classical Christian school in southern Maryland. Prather is the author of Living in the Constellation of the Canon: The Lived Experiences of African American Students Reading Great Books Literature.

In my time of researching the relevance of classics to the Black community, I have been working through the question of “Why?”

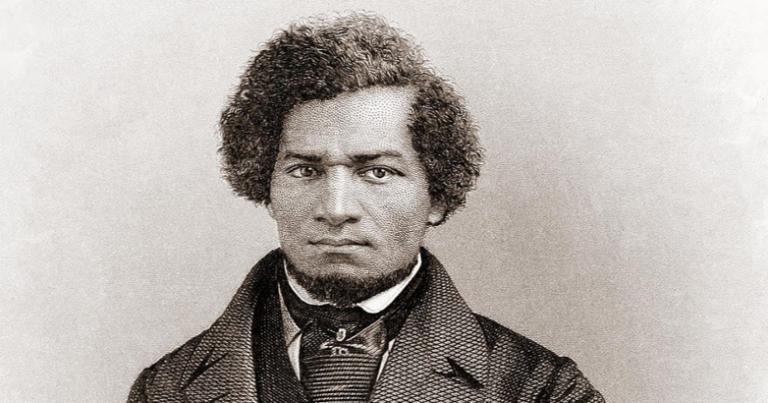

Why was there a constant pattern of a Black person reading a classic text and then being moved to fight for liberation. Only now, after writing my book, Living in the Constellation of the Canon, have I been able to articulate the reason why. It is seen when Phillis Wheatley read classics and was moved to write about her “Goliath” of enslavement and captivity. It is seen when Frederick Douglass found The Columbian Orator as a young teenager and was moved to desire freedom and the opportunity to speak against slavery. It is seen in Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail, where repeatedly he includes references from the Western Canon as a way to support his thinking on the injustices being suffered by the African American people.

What happens when oppressed African American people read the works of the canon? Many have accused classical studies of serving as a way for Blacks to assimilate into Western culture, denying their Black and/or African heritage. Others have accused Black students of the classics of being “Uncle Toms,” submitting themselves to the dominance of those who oppressed them. Yet, when I read many of the stories of Blacks who are engaged in classical studies, I find a different narrative.

Although there are numerous examples of Blacks who read classics and were motivated to fight for equality, for this piece I would like to focus on Frederick Douglass. His autobiography reveals that when he was young he was first exposed to reading classics like Cicero. He shares how it affected him:

The reading of these documents enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers.

Here we see that once Douglass began to read the true human story found in classic texts, he came face to face with the truth about his humanity. Once that light of revelation shined in his mind, he was unable to see himself as a slave any more. This makes me think of a passage from Anam Cara by John O’Donohoe, which also speaks to “awakening”:

We are always on a journey from darkness to light. At first we are children of darkness. Your body and your face were formed first in the kind darkness of your mother’s womb. Your birth was 1st a journey from darkness to light… The miracle of thought is its presence in the night side of your soul, the brilliance of thought is born in darkness… light is the mother of life. Once human beings began to search for a meaning to life, light became one of the most powerful metaphors to express… depth of life.

Paulo Freire says, “The awakening of critical consciousness leads the way to the expression of social discontents…” As Douglass read the dialogue between the slave and his master in The Columbian Orator, he became awakened to that fact that that it was possible to use reason to convince a slave owner to free his slave. He also began to see that his condition was one worth fighting for. By capturing the narrative of the human struggle from the beginning of time and through the centuries, classics allow all of us to see ourselves and to learn from those stories how to navigate the challenges of life.

In her book The Well Trained Mind, Susan Wise-Bauer says that the canon is “rhetoric in action.” This lines up with when Douglass said,

These were choice documents to me. I read them over and over again with unabated interest. They gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul, which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance. The moral which I gained from the dialogue was the power of truth over the conscience of even a slaveholder.

He was able to learn the rhetorical skills he needed to fight for the abolition of slavery. He used these same skills to convince Abraham Lincoln to free the enslaved people so they would fight in the Civil War. From a young teen until his escape from slavery at 20 years old, he practiced the rhetoric found in these texts in order fight for the freedom of his people.

What is it about classics that brings about this “awakening”? While contemplating this question, I was reminded of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and I believe I may have found the answer. Kant says,

For how should the faculty of knowledge be called into activity if not by the objects which affect our senses…partly rouse the activity of our understanding to compare, to connect, or to separate these representations, and thus to convert the raw material of our sensible impressions into a knowledge of objects which we call experience.

When I think of enslaved people, I think of the pain of the whip, the despair of the mother whose child has been sold away, and the torture of the lynching tree. These horrors connected to the senses and gave way to feelings of despair and hopelessness. These experiences gave birth to darkness. However, when an enslaved man or woman would gain access to classics, which were the same texts that the master and his family were reading, a light of understanding was born in their minds which gave way to reason. They began to become liberated in the mind so that they were driven to do one of two things: fight at any cost to liberate themselves and/or fight at any cost to liberate other enslaved people.

They were able to reason that they no longer had to accept their present condition.

In reading the human stories of Odysseus or Achilles, the mind dark with hopelessness finds the light of hope to fight for freedom and to reason on how to fight the battle against oppression. In reading the dialogues of Plato, the mind dark with ignorance on human themes finds the light of understanding that their story is connected to all other human stories. The feelings of the enslaved person were not enough to empower them to liberate themselves. There had to be an exercise in reason connected to those feelings of pain associated with enslavement. Access to classics bridged the pain of enslavement with the enlightenment of reason. Kant connects to this when he writes, “Everything practical (liberating oneself is practical), insofar as it contains motives (to be free), has reference to feelings (the pain of slavery), and these belong to empirical sources of knowledge (reason gained through reading classics).” Kant places himself in between empiricists and rationalists, creating a balanced theory for how the senses and reason work together to create some type of practical response.

The pain of slavery lead Douglass to read The Columbian Orator, and it provided the knowledge he needed to set himself and others free. I can take this same line of thinking and connect it to other activists who have fought for the equality and liberation of Black people. I share more of these stories in my book. At the root of the African Americans’ fight for liberation, you will most times find they read a classic text or a text inspired by classics.

Then to take it a step further… for the many enslaved people who embraced Christianity, faith beyond the senses and reason came into play. We see evidence of this third component in the Negro Spirituals. These songs spoke of a hope beyond earth and a faith in a power that was greater than the oppressor. So many times you will find an oppressed people whose senses, mind, and spirit were awakened; this triple threat created those like Harriet Tubman (who, although illiterate, knew the classic text of the Bible by heart), Martin Luther King (whose work in the Civil Rights Movement was grounded in classics and scripture), or Anna Julia Cooper (the great classical educator and Christian woman who was the first Black woman to bring classical education to the African American community). Matthew 4:16 says “The people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death, on them a light has dawned.” Once the oppressed people were awakened to the light of Christ there was no stopping their fight for liberation.

This journey of awakening is the journey of the African American people, and classics have played a major part in that awakening. Outlining this journey also speaks to the importance of us reading classics or the works of the canon, and also reading about how classics have been received by diverse people. Reading about how classics have inspired the African American community is one that is inspiring and enlightening about the human journey. Sharing this story with students at Howard University has been one of the most rewarding experiences I have had.

Now that the classics department may close at Howard, my heart is saddened that this narrative may be lost from the one HBCU in America that has had such a department since it was founded in 1867. To close it means that somewhere along the line the leadership lost sight of the narrative of why a college created to educate newly freed people taught the classics. It was established with a classics department because General Howard and other leaders (Black and White) recognized the “awakening” that happens when the oppressed people study classics, and they wanted Howard University to be a space where that “awakening” would continue for generations to come.