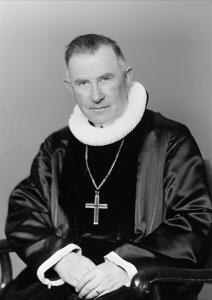

Don’t worry: this post has nothing to do with Christian responses to Donald Trump. (I’m hoping I’ve written my last words on that subject.) No, in the past month I’ve found myself thinking more about the Resistance movements of World War II, and in particular the somewhat complicated role played by one churchman: Eivind Berggrav (1884-1959), the bishop of Oslo and primate of the Church of Norway during the German occupation of 1940-1945.

While I’m of Scandinavian ancestry, we don’t spend a lot of time in that region in the WWII class I’ve been teaching this spring. After maybe five minutes last month on the Norwegian Nazi whose last name became synonymous with collaboration, Vidkun Quisling, we moved on to places like France, Yugoslavia, and Poland. (Which also happen to be the favored settings of the great spy novelist Alan Furst, whose novels I’m now re-reading.) But I’ve been thinking more about Norway because of Atlantic Crossing, the limited run series that debuted last year on Norwegian TV and is now airing on PBS.

That show focuses on the experience of the Norwegian royal family after the German invasion of April 1940. Scenes bounce back and forth across the titular ocean between London, where King Haakon and Crown Prince Olav work with a government-in-exile, and Washington, where Crown Princess Märtha drums up support for the Allied war effort (three guesses which Scandinavian American opposes her efforts) and attracts the affections of one Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But not all Norwegian leaders left their country. Some stayed and collaborated to varying degrees with the German occupation regime. Meanwhile, most of the country’s religious leaders stayed and, to varying degrees, offered spiritual, intellectual, and moral resistance to Nazism. (Alongside the courageous military efforts of resisters like those dramatized in the 2017 film, The 12th Man.)

Which brings us to Eivind Berggrav, mostly unknown to Americans unless they’ve stumbled across the biography by Edwin Robertson, Bishop of the Resistance. Published in 2000, the book pays due attention to Berggrav’s postwar work with the ecumenical movement. (Robertson worked for United Bible Societies, which Berggrav helped to organize in 1946, at the same time that he was active in the early days of the World Council of Churches.) And it tracks the twists and turn of his earlier vocational journey, which eventually found Berggrav walking in his father’s footsteps as a pastor, theologian, and bishop (though, perhaps tellingly, he took his mother’s last name) but only after stints as a journalist and schoolteacher, a period of disbelief in Christianity, and ongoing investigations into psychology and psychoanalysis.

But at the heart of Robertson’s biography is the Norwegian’s wartime experience, as a bishop who would neither flee to Sweden or England nor collaborate with Hitler and his quislings. In some ways, then, Berggrav’s story parallels those of German Lutheran theologians, like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Niemöller, who wrestled with the role of the church under totalitarianism.

In January 1941, Berggrav wrote a letter objecting to the Nazi puppet government and its attempts to interfere in the work of the church. While he affirmed Luther’s doctrine that God had ordained two kingdoms, Berggrav clarified that “the church stands in a definite relationship to the just state. This presupposes that the State… maintains law and justice, both of which are God-given orders.” In Berggrav’s view, Christians owed no duty to a state that denied its own people their inherent rights as human beings. Then that spring, Berggrav and the six other bishops of the country’s state Lutheran church rejected the government’s demand that it confine its preaching and teaching to “that which is purely edifying and eternal in the Gospel,” responding instead that “The eternal Word should shed light upon what is foremost in our daily life and in the lives of all of us.” And while the occupiers tried to play upon the church’s suspicion of Communism, all but a handful of the country’s Lutheran pastors followed Berggrav’s lead in refusing to speak in favor of Germany’s June 1941 invasion of Norway’s officially atheistic neighbor, the Soviet Union.

In February 1942, the German occupiers installed Quisling (a pastor’s son who had established a small Norwegian Nazi party in the 1930s) as minister-president; simultaneously, he declared himself Supreme Bishop of the state church and attempted to replace church youth groups with a new organization modeled on the Hitlerjugend. In response, Berggrav, the other bishops, and some 93% of the country’s Lutheran clergy resigned their administrative functions — though they continued their pastoral work without salary or official status. That Easter, pastors read from their pulpits a Norwegian version of the Barmen Confession, Kirkens Grunn (The Foundation of the Church). Edited by Berggrav, it repeated his update of Luther’s two kingdoms argument:

A just authority is God’s grace and gift, and we declare, together with the apostle [Paul], that for reasons of conscience we pledge to obey such an authority in all temporal affairs. But the words for reasons of conscience mean that it is for God’s sake we obey authority, and that therefore we must obey God more than people. The apostle has clarified how this authority is to be recognized. Just authority is recognized by its not being a terror to good conduct, but to bad (Romans 13:3).

Should then the authorities become a terror to souls who follow God’s way, then they are no longer an authority according to God’s will, and then it becomes the church’s duty before God and man to let such an authority hear the word of truth. As Scripture says, “Son of man, I have made you keeper, and when you hear a word from my mouth, then you must warn them” (Ezekiel 3:17 ff.).

The following week, Berggrav and other church officials were arrested, with Oslo’s bishop confined to house arrest for the rest of the war at his holiday cabin in Asker.

(One of his projects while imprisoned was to update the Norwegian translation of the Bible. “In times of war and occupation,” he wrote, “the Bible is a clear light to what should be done; but in times of prosperity it becomes a very difficult book.”)

In June 1942, the New York Times featured Berggrav as the second in its series of “Churchmen Who Defy Hitler” (a day after the German Catholic bishop Clemens von Galen, who famously spoke out against Nazi euthanasia in the middle of the Holocaust). Concluding the profile, missionary Henry Smith Leiper admitted that “Bishop Berggrav is no longer in a position to exert direct influence over his people, but he has laid the groundwork of an opposition the Nazis will find it hard to overcome.” As the Germans and their collaborators began to round up more of Norway’s 1,500 Jews that October, Berggrav inspired a pastoral letter read in all churches on the anniversary of Kristallnacht: “Were we silent on this legalized injustice against the Jews, we should share responsibility and guilt for this injustice.” (In the end, about 40% of Norwegian Jews died in the Shoah, and Robertson admits that “The resistance movement, including the church, acted too late to prevent the massacre.”)

A year into his house arrest, Time reported that “Bishop Berggrav in confinement is as strong a moral force as all the churchmen at liberty in the land.” The American magazine claimed that Norwegians compared Berggrav favorably to his fellow Lutheran pastor, Martin Niemöller, who, “they insist, was sent to a concentration camp only because he did not like the Nazis barging into church affairs. Berggrav, on the other hand, took his stand not merely on spiritual grounds, but also because he detested their political theories and said so.” A year later, Berggrav graced the Christmas cover of the same periodical.

In reality, Robertson reports, Berggrav’s legacy in his own country was more complicated than that. Time may have claimed that “Tall Bishop Berggrav has grown even taller in the estimation of his enslaved countrymen,” but many Norwegians remembered the more conciliatory figure of 1939-1940. In the first winter of the war, Berggrav’s attempts at diplomacy included a two-hour interview with Hermann Göring, trying to convince the Luftwaffe chief to bring about an end to the war. Shocked by the German invasion a few months later, the bishop publicly encouraged civilians not to resist — both on radio and in person, in a scene photographed by the Germans. After the war, he drew criticism for opposing the death penalty for collaborators like Quisling.

For all Time’s claims that Berggrav’s “militant Christianity has brought about a resurgence of religious fervor” in a country whose state church “had largely lost touch with the common people,” he could do little to reverse the deepening secularization of Norwegian society in the postwar period. By contrast, six months in the U.S. in 1954 left him impressed (in Robertson’s summary) that the church in this country “seemed to be at the center of all human life and embraced a much wider sphere of interest than it did in Europe.” Yet he struggled to find his footing in a Cold War world, with Berggrav finding fault with Soviet Communism, American capitalism, and even the welfare state championed by Norway’s Labour Party.

Nevertheless, Georgetown professor Diane Yeager came to a high view of Berggrav’s wartime resistance in a 2006 evaluation. Without placing him alongside Bonhoeffer or Niemöller, she concluded that “he was a man who withstood grave trials with courage and grace, who led an organized, principled, and surprisingly effective movement of Christian resistance to state tyranny, and who has contributed in a careful, practice-based way to Lutheran thinking about the situation of the Christian in relation to civil and political authorities.”