I am weirdly interested in who becomes the next president of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) next month. Weirdly, because I have never been a Southern Baptist. But before joining an Anglican church last year, I belonged to other evangelical Baptist or Baptistic churches for my entire adult life. The evangelical Baptist world has been central to my spiritual formation, and I take a personal interest in its development. So I read with interest a forum hosted by the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood—a complementarian organization committed to different roles for men and women—on the four candidates’ beliefs about women’s place in the church.

Admittedly, this is also because I take a professional interest: Central to the debate on the future direction of the SBC is conflict over gender roles in the church. Ever since Beth Moore preached on Mother’s Day in 2019, the question of just how to interpret the denomination’s doctrine of complementarianism has become increasingly divisive.

Simultaneously, some Southern Baptists have accused others of becoming too “woke,” too concerned with social justice, and especially with “critical race theory” (CRT), which teaches, among other things, that racism is systemic and not merely personal. Racism is baked into some of the ways our society is set up, and hence combatting it requires not only personal repentance but purposeful social action. It is debatable whether any two Southern Baptists talking about CRT are actually discussing the same thing. I suspect it is functioning like the word “feminism,” defined multiple different ways and mostly used in casual conversation as a compliment or a slur.

These debates have led to high-profile departures: Beth Moore left the SBC for an unaffiliated Baptist church. Russell Moore resigned as president of the convention’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) to take a job at the more broadly evangelical Christianity Today. Several Black pastors pulled their churches out of the convention. And on the other side of the divide, Owen Strachan left Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary for a more fundamentalist startup seminary in Arkansas.

Membership numbers continue to decline. The combination of the departures and the numbers have created a sense of crisis about the SBC’s future direction. One party argues that the hemorrhaging is the result of theological liberalization. They claim that greater attention to racial justice and loosening restrictions on women’s activities is symptomatic of a drift away from focusing on the gospel of individual conversion. Another party argues the denomination is losing youth precisely because it resists attention to social concerns.

In other words, it’s a redux of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the early twentieth century, and gender is at the center once again.

In the nineteenth century, American evangelicals held together belief in the necessity of individual conversion (to reconcile with God) and of social reform (to love neighbor). One of the great tragedies of American Christianity was that disagreements over doctrine subsequently made it more difficult to continue to emphasize both. Doctrinal traditionalists increasingly shied away from social reform when it became associated with doctrinal liberals who abandoned historic tenets of the faith like the deity of Christ, sacrificial atonement, or the physical resurrection. And Christians who cared about reform sometimes let go of a previous emphasis on individual conversion when they saw conservative brothers and sisters denigrate action for social change.

Today, frankly, not nearly as much is at stake. Most evangelicals who advocate egalitarianism (no gender hierarchy in church or home) or appropriating insights from CRT still hold to what became known as the inerrancy of Scripture, a doctrine whose current formulation dates back to the years leading up to the fundamentalist-modernist controversy. Inerrancy meant that the Bible was completely accurate in its original manuscripts, and hence Christians could be confident in the traditional doctrines about Christ deriving from the Scriptures. But while inerrantists agreed about many doctrines, they did not interpret all passages the same, and rightly so. It was an approach to the Scripture, not a systematic theology.

When was an interpretation evidence of creeping liberalism and when was it just different from yours? As a marker of identity and safety in a time of genuine doctrinal threat, many conservatives slid toward a more literal interpretation of New Testament passages. Not necessarily more accurate to the original intention, but closer to the surface of the text. No one could accuse you of being liberal if you told women to never teach in church when there was a text that read “women should keep silent in the churches” (1 Corinthians 14:34, ESV). You might be wrong, but at least you wouldn’t be liberal. Limitations on women’s roles became a shibboleth for belief that the Bible was accurate.

(One of the times I am proudest of my younger exegetical self was when I was studying a passage on women’s roles during college and the study leader suggested that when in doubt, we should err on the side of caution rather than permit an activity God might forbid. I instinctively countered, “No. We shouldn’t err.”)

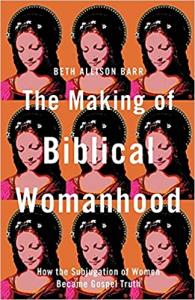

These dynamics were on display again this week over a misunderstanding of my colleague and fellow blogger Beth Allison Barr’s treatment of inerrancy in The Making of Biblical Womanhood. A graciously critical review appreciated her contributions but claimed Barr rejected inerrancy, which made her argument problematic. A less gracious comment from a senior editor at Christianity Today accepted that assessment and dismissed the entire book as “unhelpful.” Only Barr does hold to the accuracy of the Scriptures, as is clear from her chapter on interpretations of Paul. Barr is a historian rather than a theologian, so when she wrote about how an emphasis on inerrancy has harmed women, she was using “inerrancy” to refer to a historical theological movement, not a theologically precise category—inerrancy as it really has been, rather than as it ought to be.

These dynamics were on display again this week over a misunderstanding of my colleague and fellow blogger Beth Allison Barr’s treatment of inerrancy in The Making of Biblical Womanhood. A graciously critical review appreciated her contributions but claimed Barr rejected inerrancy, which made her argument problematic. A less gracious comment from a senior editor at Christianity Today accepted that assessment and dismissed the entire book as “unhelpful.” Only Barr does hold to the accuracy of the Scriptures, as is clear from her chapter on interpretations of Paul. Barr is a historian rather than a theologian, so when she wrote about how an emphasis on inerrancy has harmed women, she was using “inerrancy” to refer to a historical theological movement, not a theologically precise category—inerrancy as it really has been, rather than as it ought to be.

So how should those of us committed to the reliability of the Scriptures, from Barr to the candidates for the SBC presidency, go about interpreting New Testament passages on gender roles? Common, and excellent, questions include: What is the context of the passage? Does our interpretation contradict other parts of Scripture? How has the church in other times and places interpreted the passage?

I would additionally propose that to really take the truth of the biblical text seriously, we need to ask one other oft-neglected question when interpreting the Pauline passages about men and women’s roles:

Does this interpretation even make sense?

Here’s what I mean: A neglected verse in our interpretation of gender passages is Jesus’s words to His followers in John 15:15: “I no longer call you servants, because a servant does not know his master’s business. Instead, I have called you friends, for everything that I learned from my Father I have made known to you” (NIV). God absolutely has the right to ask things of us without explanation. But—and this is part of the radicalness of His choice to reveal Himself in Christ—starting in the New Testament, He doesn’t. Sit with that. So an absolutely essential question to ask when interpreting difficult passages is “Why?” Not why in the sense of “Why? I don’t feel like it.” But why in the sense of “Why? I want to make sure I am understanding You correctly so I can be living out the instruction with the proper end in mind.”

I therefore propose two subset questions to test the reasonableness of any interpretation of the New Testament’s passages on gender:

- What would this interpretation mean for church life on the ground? Would that be consistent with what we know about God and His plans for the church?

For example, if the correct interpretation of the Pauline corpus is that not only may women not serve as elders of a church, but they may also not teach the faith to adult men, then a church would end up in the following situation: Women in a local church would have access to 100% of the teaching gifts that God had bestowed on that church. They could hear both men and women expound the Scriptures. Men, on the other hand, would have access to only 50% of the teaching gifts God had given that church; they could learn only from other men. So barring women from teaching adult men about God cannot be the right interpretation of Paul because it is unreasonable to believe that God would discriminate against men that way. We Americans tend to think that this is a debate about the right to teach, that teaching is the privilege in question. We’re wrong. The privilege is learning. It is particularly unreasonable to limit women’s teaching if you also believe that God asks only men to govern the church—the governors would be taken exclusively from the subset of the church with access to only half the church’s wisdom! And it especially doesn’t make sense if you actually believe in gender complementarity, that women and men see things from different angles. We therefore need one another to interpret God’s word rightly.

Back to the SBC presidential candidates. One would permit women teaching mixed-sex adult Sunday School, although not women serving as elders. I disagree with the prohibition on female elders, but this stance is consistent. (I have, in fact, belonged to several churches that take this position.) There is a logical distinction between teaching and governing. For example, I am a professor and also, as of recently, a graduate program director. I am rapidly learning that these positions require different activities and skills! (This candidate would not, however, permit a woman to preach from the pulpit, which I think is inconsistent with his position, but not as big a deal: much more Bible teaching than guest preaching goes on in the average church.)

But the other three candidates draw a hard line that prohibits men from learning from women. Because the Scriptures teach that God distributes spiritual gifts without respect to any natural category such as sex or race, this position is fundamentally incoherent. It seems therefore to be more a sign of their commitment to the veracity of Scripture (“my interpretation is more literal than your interpretation”) than an actual commitment to thoughtfully wrestling with biblical teaching. It seems, in fact, to be “virtue signaling”—an accusation that would likely horrify them because conservatives tend to hurl it at liberals. This is Barr’s point about what the word “inerrancy” can mean on the ground.

- If we lived out this interpretation, what would we be saying about God? What is beautiful about it?

What struck me most about the presidential candidates’ responses to the CBMW questionnaire was that, with one partial exception, none of them cast a vision for why God asked the church to behave in the way they believe that He did. The coherence and beauty, yea purpose, of God’s guidelines never made it into their defense of their exegetical position. None of them explained how limiting women’s service in the church was good news, a picture of the fullness of life offered in Christ. This absence is what one would expect if gender roles had become a shibboleth, a proxy for inerrancy. They simply defended their interpretation as the one most accurate to the text. Accuracy is an important starting point; only true things can be really beautiful in the end. But while it is necessary, it is not sufficient. There is no end goal, no telos, only mindless obedience.

Some complementarians do of course seek to cast such a vision. I have never read a version that I find fully convincing, but I have found wisdom in parts. As I tell my students, I believe one reason complementarian teaching remains popular is that many people consider being male or female a central part of their identity. They want it to mean something. And Christians who hold a theology of a purposeful creation rightly ask what God intended by two sexes. Unfortunately, I have yet to encounter a robust egalitarian theological treatment of the meaning and significance of sexual difference.

So my final question for egalitarians is: If such a work exists and I’ve missed it, would you let me know? And if not, who wants to write it?