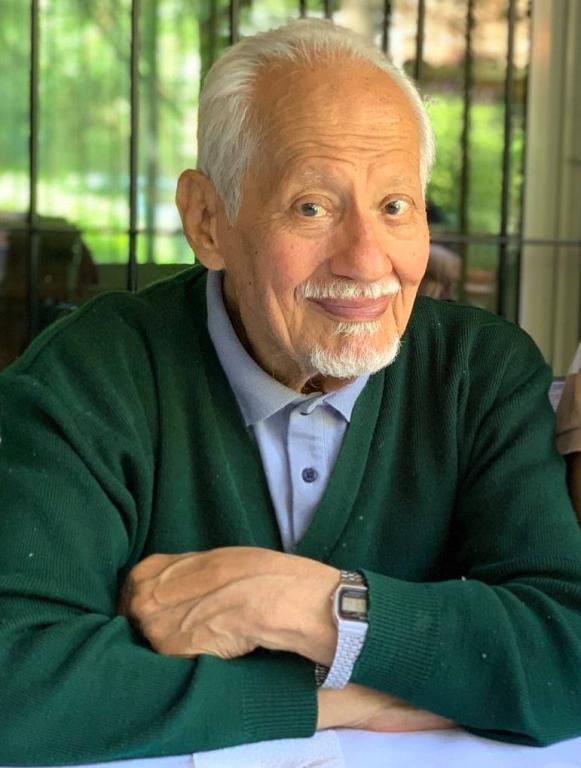

April 27, 2021, was a monumental day in the field of World Christianity. That day marked one hundred years since John Stott’s birth. On the very same day, theologian-editor-evangelical provocateur C. René Padilla died. Already he has been remembered in dozens of tributes that laud his nurture of young theological students, deep love for his wife Catharine Feser Padilla, and pugnacious insistence on “Integral Mission,” the idea that social action and evangelism are inseparable. Indeed, his long career as a provocateur who challenged evangelical Christian Americanism is what has most fascinated me as I chronicled the evangelical left and the influence of World Christianity on American evangelicalism. Padilla earned his reputation as an enfant terrible who showed no fear in challenging white evangelical kingmakers at Fuller Theological Seminary, Christianity Today, and the Evangelical Theological Society.

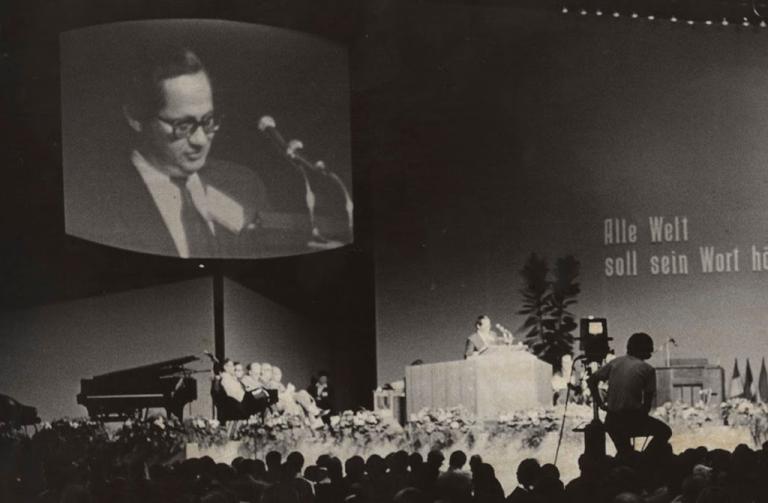

There is no better—and no more significant—example of Stott’s and Padilla’s activism than the International Congress on World Evangelization in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974. Here’s the story I narrated in Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity: On its third evening, the Congress took a dramatic turn. A group of mostly non-Western delegates calling themselves the “radical discipleship caucus” met to plot their resistance to Western dominance of the Congress. The dissatisfaction, one of the caucus members later explained, had “bubbled” up out of irritation with an establishment sensibility that did not take social justice seriously. More than two hundred people opted out of a scheduled tour of nearby Geneva to join the chaotic ad hoc meeting on Sunday night. It opened with a sixties-style folk song featuring ominous lyrics: “This is the calm before the storm.” Solomon Mergie of Papua New Guinea offered a prayer, which was followed by a series of plaintive monologues from Australian prophet Athol Gill and Latin American Theological Fraternity members René Padilla and Samuel Escobar. Their extemporaneous speeches, diverse in style and frequently punctuated by laughter, grumbling, amens, and applause, were followed by hours of intense discussion.

There is no better—and no more significant—example of Stott’s and Padilla’s activism than the International Congress on World Evangelization in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974. Here’s the story I narrated in Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity: On its third evening, the Congress took a dramatic turn. A group of mostly non-Western delegates calling themselves the “radical discipleship caucus” met to plot their resistance to Western dominance of the Congress. The dissatisfaction, one of the caucus members later explained, had “bubbled” up out of irritation with an establishment sensibility that did not take social justice seriously. More than two hundred people opted out of a scheduled tour of nearby Geneva to join the chaotic ad hoc meeting on Sunday night. It opened with a sixties-style folk song featuring ominous lyrics: “This is the calm before the storm.” Solomon Mergie of Papua New Guinea offered a prayer, which was followed by a series of plaintive monologues from Australian prophet Athol Gill and Latin American Theological Fraternity members René Padilla and Samuel Escobar. Their extemporaneous speeches, diverse in style and frequently punctuated by laughter, grumbling, amens, and applause, were followed by hours of intense discussion.

If the accents were diverse, the message was uniform. Those gathered intended to press the larger Congress, comprised of over 2,400 representatives from 150 nations, on the social implications of true and radical evangelization. Gill, the Baptist founder of an intentional community called House of the Gentle Bunyip, urged delegates, entombed in a concrete bunker of respectability, to break free of the modern amenities of the Palais de Beaulieu conference center. Evangelicals needed to recover Scripture’s “cutting edge.” God’s people, Gill continued, included tax collectors, sinners, the poor, and prostitutes. Padilla, who plotted the rebels’ gathering, made a case for radical biblical ethics. He asked, “Are we really a community of love, of reconciliation, that serves as a basis for resistance for the conditioning of the world with all its values, its prejudices, including racial and social prejudice? Or is the church just a reflection of the whole society?” To applause, Escobar accused Westerners of merely “reproducing pagans or semi-Christians in our own likeness, instead of really evangelizing.” The architects of the Congress were evangelizing pagans into followers of Americanism, not authentic Christianity. “Nothing against Americans,” one delegate said to lots of laughter. “We all love them and are grateful to them.” But the message of Jesus was most certainly not “this American-culture Christianity” that was plaguing Lausanne.

The caucus then challenged the proposed Lausanne Covenant. “This statement clearly doesn’t come out of the life of this conference. I presume it was largely prepared before it. It’s got phrases we’ve been hearing for donkey’s years, and it doesn’t speak to contemporary life,” complained one critic. Another proposed writing an entirely different document that would articulate the concerns of non-Westerners. As the caucus contemplated its next move, a security guard notified the caucus that the building was closing. The gathering ended in prayer, which was cut short as staff began to shut and lock the doors.

A smaller group of six decamped to another location in order to plot their next steps. But first John Stott, the primary author of the working draft of the Lausanne Covenant, intercepted the dissenters. Stott was sympathetic to their concerns, but he worried that an alternative Covenant might cause the Congress to “end with some degree of misunderstanding, confusion, even disunity.” He convinced the caucus’s leaders to instead release a “report” that would be included in the official compendium of proceedings. But late that night, an intermediary was dispatched back to Stott. The leaders had not been able to convince the “rank and file” of the caucus to go along with the compromise. Instead, they planned to double down by publicly releasing the dissenting document in the morning and then recruit hundreds of signatories.

The impact of the Sunday night rebellion hit the Congress with full force on Monday. Copies of “A Response to Lausanne,” full of stark words of resistance, circulated quickly through the Palais de Beaulieu. The polemical document cited “demonic” attempts “to drive a wedge between evangelism and social action.” It confessed that evangelicals were guilty of triumphalism, arrogance, and social sin. It charged that they had “neglected the cries of the underprivileged” and allowed “eagerness for quantitative growth to render us silent about the whole counsel of God.” More than 500 delegates, who comprised roughly a quarter of the assembly, immediately signed it.

The scene that followed almost seemed choreographed. Samuel Escobar, scheduled to give a plenary address to the entire assembly, delivered a trenchant critique of Western imperialism. American conservatives, he said, might justifiably critique theological rivals on the left. But they had their own blind spots. “We should also reject,” Escobar explained, “the adaptation of the Gospel to the social conformism or conservatism of the middle class citizen in the powerful West.”

Then came René Padilla. Fortified by prayers from home—in Buenos Aires, Catharine Feser Padilla gathered her children around a globe and told them, “Today, when he gives his talk here, in Lausanne, Switzerland, Papi will say some things that not everyone is going to want to hear. Let’s pray for him and for the people listening to him”—Padilla delivered his address. An Ecuadorian who had attended Wheaton College, studied with noted New Testament scholar F.F. Bruce at the University of Manchester, and traveled widely in the United States, Padilla directly confronted the technocratic Church Growth group. He condemned the “American culture-Christianity” that had turned the gospel into “a cheap product.” Missionaries from the United States, he continued, were captive to a “fierce pragmatism” that “in the political sphere has produced Watergate.” They were exporting an obsession with efficiency and the “systematization of methods and resources to obtain pre-established results.” They had identified the Gospel with worldly power, perpetuated patterns of dependence, and conflated “Americanism with the Gospel.”

Time magazine described Padilla’s “most provocative” keynote address as having “assailed the sort of easy Christianity the U.S. has often exported.” Delivering the speech in Spanish to accentuate resistance to colonialism and to “teach Western delegates the experience of listening to a translator,” Padilla earned one of three standing ovations of the Congress. It was the longest and most sustained applause to that point in the Congress, and it stopped only when song leader Cliff Barrows began to lead a hymn. More than a few international delegates saw “deep political overtones” in the ovation’s premature end. More than a few Western organizers saw Padilla as the enfant terrible of the Congress. Some organizers, with crossed arms and stone faces, were “so mad,” Padilla later recalled, that they refused to acknowledge or speak to him after his address. He had portrayed, said one Western delegate, “so patently a caricature as to create static that cannot but block . . . many insights which people attending the conference will need.”

Delegates from the West and non-West alike recognized the import of the moment, which ultimately shaped the language of the document that would emerge from the conference. “With this covenant,” Padilla said, “evangelicals took a stand against a mutilated gospel and a narrow view of the Christian mission.” Canadian evangelist Leighton Ford, Billy Graham’s brother-in-law, noted, “If there has ever been a moment in history when evangelists were in tune with the times, it surely must have been in July of 1974. Lausanne burst upon us like a bombshell. It became an awakening experience for those who attended.” After Padilla’s address, Graham, ever the diplomat, pronounced it “one of the most brilliant contributions for the analysis of the evangelistic task today.” According to a British delegate, the speeches were “much more deeply felt than many Western evangelical Christian leaders here could have expected.” Padilla himself, greeted by a deluge of hugs and congratulations after his speech, was “surprised at the number of Asians and Africans and Latin Americans who felt represented by what I said.”

The battle continued for decades. Padilla continued to press, and he continued to be marginalized by the evangelical establishment. Missiologist C. Peter Wagner wrote a scathing retrospective in Christianity Today of Padilla’s activism, which appeared to ignore the gravity of individual moral sins, had tried unsuccessfully to “torpedo” the Congress with an “attempt to confuse evangelism with social action.” He and Escobar were not invited to join the continuation committee that met in Mexico City six months later. At a 1977 “Colloquium on the Homogenous Unit Principle” at Fuller Seminary, Padilla again clashed with Wagner. A disgusted John Stott wrote in his diary that when Padilla got up to speak, Wagner and his colleagues “put down their pads and pens, folded their arms, sat back and appeared to pull down the shutter of their minds.” According to one report, Christianity Today booted Padilla off its board of directors in the 1990s.

Which is what makes Christianity Today’s obituary of Padilla last week so remarkable. In the end, Padilla clearly won over the evangelical cosmopolitans. Some of the highest praise of Padilla after his death came from Christianity Today, Fuller Theological Seminary, and a long list of Never-Trumpers. Of course, that’s a somewhat hollow victory for advocates of Integral Mission now, given Christianity Today’s own marginalized position in the post-2016 evangelical landscape.