I’m pleased to welcome Ulrike Stockhausen to the Anxious Bench. Ulrike is the author of The Strangers in Our Midst: American Evangelicals and Immigration from the Cold War to the Twenty-First Century, just out with Oxford University Press. She currently works as the Digital Science Communication Officer at the Max Weber Stiftung – Foundation German Institutes in the Humanities Abroad in Bonn, Germany. –David R. Swartz

***

David: Welcome to the Anxious Bench! Please tell us what your new book is about.

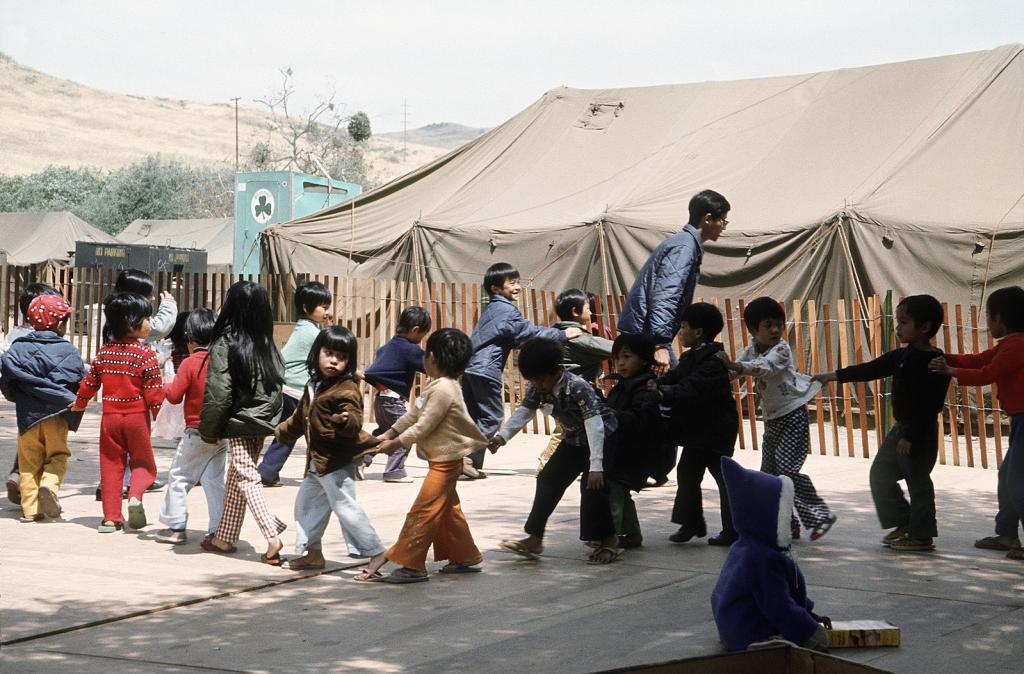

Ulrike: The Strangers in Our Midst tells the story of how American evangelical Christians have responded to refugees and immigrants to the United States. I trace how Southern Baptists channeled their anti-communism into a large-scale sponsorship campaign for Cuban refugees in the 1960s, how evangelicals developed an elaborate theology of hospitality which led them to welcome refugees from Southeast Asia in the 1980s, and how their welcoming attitude shifted when increasing numbers of undocumented immigrants from Latin America and other parts of the world started making their way to the US in the 1990s and 2000s. In today’s heated political climate, it’s easily forgotten that evangelical Christians once were a pillar of refugee resettlement in the United States. They have acted as sponsors for tens of thousands of refugees and have offered legalization assistance to thousands of undocumented immigrants. What was fascinating to me is that until the 1980s, evangelicals didn’t distinguish between legal immigrants and refugees and “illegal” undocumented immigrants — they welcomed and assisted all newcomers. This stance changed with their growing ties to the Republican Party and especially with the GOP’s more restrictive position on immigration in the 1990s.

In the first part of the book, I explore this history of evangelical refugee resettlement. In the second part I seek to understand why evangelicals shifted their views on immigration in the 1990s. I then follow a new generation of evangelical leaders who — prompted by their Latinx brothers and sisters — sought to shift mainstream evangelicals’ views on immigration – a battle which became increasingly pressing during the Trump years.

David: In the introduction, you offer this damning line: “As the Republican Party shifted from supporting a relatively open immigration policy toward promoting a much more restrictive platform, evangelical leaders—by now safely in the GOP’s fold—brought their theology in line with their politics.” Do you see this as the dominant motif—or can you point to counterexamples of theology shaping politics?

David: In the introduction, you offer this damning line: “As the Republican Party shifted from supporting a relatively open immigration policy toward promoting a much more restrictive platform, evangelical leaders—by now safely in the GOP’s fold—brought their theology in line with their politics.” Do you see this as the dominant motif—or can you point to counterexamples of theology shaping politics?

Ulrike: You are absolutely right, it is a damning line! Of course, in theory, people of faith hope that their theology impacts their politics, not the other way around. And for people who take the Bible as seriously as evangelicals do, this should be even more true! But interestingly, that wasn’t always the case. What was fascinating to me is that this was the case for conservative and progressive evangelicals alike. Conservative evangelicals shed their welcoming theology in favour of a much more restrictive position when that became the Republican Party’s immigration platform. For progressive evangelicals, their opposition to the United States’ involvement in Vietnam caused them to be much more reluctant to resettle Vietnamese refugees than their mainstream evangelical counterparts. So yes, this is a dominant motif in the book. While it’s true for all parts of the evangelical mosaic that I look at, it’s especially striking among mainstream evangelicals. In mainstream evangelical publications, I actually found a shift in the Biblical material which evangelical authors reference when talking about immigration. In the mid-2000s, evangelical authors start to include “submission to the authorities” verses — which are entirely missing in the debates of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

But there are also counterexamples of theology shaping politics. I found the Southern Baptist Convention’s leadership to be particularly interesting in this regard. Despite being staunch political conservatives, a number of Southern Baptist leaders came out in recent years to publicly support comprehensive immigration reform (that is, immigration reform which includes a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants). In the film The Stranger, produced by an evangelical activist group called The Evangelical Immigration Table, Southern Baptist leader Barrett Duke recalls that he, too, thought that undocumented immigrants should be deported until he decided to look at the issue through the lens of a Christian, not an offended citizen. Duke, who at the time was Vice President for Public Policy and Research at the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, which is the SBC’s public policy arm, mirrors the experience of many of the mainstream evangelical leaders. Prompted by their Latinx colleagues like Samuel Rodriguez of the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference, they became convinced that the Bible mandated a welcoming approach to all immigrants, and that as evangelical Christians, they should lobby Congress to pass comprehensive immigration reform.

David: How did evangelical leaders “sell” refugee settlement to their constituents?

Ulrike: “Sell” is the right word – there was a lot of convincing that needed to be done. The arguments that evangelical leaders drew on varied over time. Sometimes they were more overtly political or even ideological, sometimes less so, sometimes they included a lot of Biblical references, sometimes none. In the first large-scale evangelical refugee resettlement initiative — finding new homes for the Cuban refugees in the 1960s — ideological arguments loomed large. There was a lot of talk about the refugees as freedom seekers and in general, the arguments didn’t look much different from the U.S. government’s public relations campaign. Both in the case of the Cubans and in the case of the Vietnamese refugees, evangelical leaders went to great length to describe the newcomers as good citizens who were worthy of their help. I was particularly struck by how evangelical publications would always include the Cuban expats’ former professions in the descriptions (such as, “In Cuba Miguel was a salesman for Procter & Gamble”)[1]. Biblical references started to appear more broadly in the context of the Southeast Asian refugees. In order to win evangelical sponsors for Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees, evangelical leaders emphasized the many Scriptural commands given to the people of Israel in the Old Testament. The Israelites were repeatedly called to remember their own experience as “strangers” in Egypt and thus to welcome the strangers in their midst — most famously in Leviticus 19:34: “The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.” While these “stranger” verses abound in the Old Testament, the New Testament also includes numerous calls to hospitality, and of course, Jesus’ famous words, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me,” which were used to remind evangelicals that if they welcomed refugees, they welcomed Jesus himself (Matthew 25:35). In the case of the Southeast Asian refugees, there was also a lot of dire life-or-death language, which reflected the humanitarian spirit of the decade as well as the gravity of the situation. More recently, evangelical leaders have used a mix of biblical and educational arguments to convince their co-religionists of the need for comprehensive immigration reform. One mobilizer for the Evangelical Immigration Table, Michelle Warren, called this approach “good stories, good information.” While evangelical leaders always included a Biblical foundation for their activism, a lot of the material gives very simple information on the immigration process, usually in the context of individual life stories.

David: You describe an “anti-immigrant backlash” that emerged in the early 1990s—and then how a “theology of hospitality” was subsumed by a discourse of “submission to the authorities”—in the 2000s. Where did this come from?

Ulrike: The fact that it was only in the 1990s that evangelicals started to view undocumented immigration as running counter to the Apostle Paul’s mandate to submit to the governmental authorities really fascinated me when I was researching this book. Evangelicals have a long history of supporting law and order type policies (as showcased by Billy Graham’s enthusiastic support for Richard Nixon’s presidential campaigns).[2] They have also historically been very supportive of the police force, as Adam Griffith argues in his book, God’s Law and Order.[3] So I would have expected to find references to the Biblical passages that call Christians to “submit to the authorities … that which God has established” (Romans 13:1, see also 1 Peter 2:13) when evangelical Christians first started discussing undocumented immigration in the 1980s. But back then, these verses were completely missing from the conversation! Up until the 1980s, evangelicals from all ends of the political spectrum agreed on a common theology of hospitality, which focused on the Biblical calls to love and welcome the stranger. It was only in the mid-1990s that evangelicals started to think about immigration in terms of law and order, and the “submission to the authorities” language started dominating the debate even later.

I think three factors played into this development. First, evangelicals were disappointed with what they viewed as Ronald Reagan’s failed amnesty program. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which Reagan signed into law in 1986 and which included a legalization component for undocumented immigrants, drew widespread support among evangelicals. Evangelical organizations and churches ran legalization centers for undocumented immigrants as part of the IRCA. But when the number of undocumented immigrants kept rising in the 1990s, they felt that “amnesty” had failed to solve the problem of unlawful immigration. At the same time, the Republican Party dramatically changed its platform on immigration in the 1990s, trying to present itself as the get-tough party on undocumented immigration. This was also when the term “illegal immigrants” started to surface, and it’s when evangelicals started to connect their support for law and order with their position on immigration. Many started to think of undocumented immigrants as “law breakers.” While the GOP retained evangelicals’ support for their get-tough measures, this approach didn’t work out that well overall, and so by the early 2000s, President George W. Bush actually backed comprehensive immigration reform — including the disputed legalization component. Then the September 11, 2001 attacks happened and public support for comprehensive immigration reform eroded, giving way once again to restrictive immigration proposals such as The Border Protection, Anti-terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005, also known as the Sensenbrenner Bill. Also as a result of 9/11, evangelicals grew increasingly wary of Muslim immigrants, and immigration once again became a hotly disputed subject at the national level. Evangelical denominations and publications, which had only rarely talked about immigration policy and immigrants in the 1990s, reflected this renewed focus on immigration. They started to re-examine the subject from a theological perspective. Now they brought in language from Romans 13 (as well as much more obscure references such as comparing undocumented immigrants to the “thief in the night” in John 10). I don’t think that evangelicals remembered that their brothers and sisters had developed such a complex theology of hospitality, nor were (and are) many evangelical Christians aware of their movement’s impressive history of participating in refugee resettlement and legalization efforts. To them, both because of their historical support for law and order policies and as a reflection of their strong ties to the GOP, references to the Bible’s calls to “submit to the authorities” came naturally.

David: There’s a big debate among historians about whether evangelicalism has changed since the 1950s or whether Trump revealed evangelicalism in its populist fullness as it has been all along. Which side do you fall on?

Ulrike: I think that the evangelical movement is, and always has been, incredibly diverse – evangelicals share important religious convictions, but the way they live out their faith and the political conclusions they reach can be tremendously different. I don’t think that the Trump era exposed evangelicalism as it was all along. Instead, I think that it shed light on and empowered one segment of evangelicalism that has always been there. In their recent book Taking America Back for God, sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry found that while about 50 percent of the people who they identify as Christian nationalists are evangelicals, twenty-five percent of those who resist or reject Christian nationalism are also evangelicals. They thus conclude that Christian nationalism is much more “ethnic and political than it is religious.”[4] Many of the Christian nationalist evangelicals might even fall into the category so aptly described by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Russell Moore as people who “may be drunk right now, and haven’t been into a church since someone invited them to Vacation Bible School sometime back when Seinfeld was in first-run episodes.” So, while there is certainly a significant overlap between populist nationalists and evangelicals, there are also other parts of the spectrum. My hopeful self believes that these are the parts that are growing (and growing up) within the evangelical movement.

But it’s also easy to forget that American evangelicalism has become a lot more conservative since the late 1970s – regarding abortion, for instance, but also with respect to the ordination of women and other theological issues such as biblical inerrancy. In 1970, as many as 70 percent of Southern Baptist pastors supported abortion to preserve the mental or physical health of the mother, an unthinkably high percentage from today’s perspective. This increased political and theological conservatism went hand in hand with the increased politicization of the evangelical movement (again, Southern Baptists were once known for their ardent support for the separation of church and state). While the evangelical movement has historically shown support for nationalist and nativist positions, I think that this segment has grown since the Reagan years and now, as we have seen, has become emboldened in the Trump years.

David: You’re a German scholar. How did come to study American history—and ultimately write a dissertation on U.S. immigration history—at the University of Münster?

David: You’re a German scholar. How did come to study American history—and ultimately write a dissertation on U.S. immigration history—at the University of Münster?

Ulrike: I wonder about that myself sometimes! It started out in my teenage years when I became interested in politics. This was the time of 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and you couldn’t discuss global issues without also being interested in how, for instance, an American president was able to get the support for these wars that he needed. My family has ties to the U.S., so I didn’t want to chime into the anti-American of that time here in Europe because I knew and cherished my American friends. Ultimately, my interest in American politics and history started out with the question: How could my American friends and I — though we shared important religious convictions — have such dramatically different political positions? This was the question that drove me to pursue graduate studies in North American Studies in Berlin, and it’s what led me to Münster, which is the place to go in Germany if you are interested in the intersection of religion and politics. It was interesting to be in such an outsider position when I was researching the subject. When I was wrapping up the narrative, it was helpful to be physically removed from the deeply polarized political climate in the US. I think it helped me keep my sanity sometimes.

Thank you so much for welcoming me to The Anxious Bench and for discussing these questions with me!

David: Thank you!

Citations

[1] Jo Ann Parker, “Cubans in Our Churches,” Home Missons 34, no. 7 (July 1963): 10.

[2] For more on Graham’s relationship with Nixon, see Steve P. Miller, Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican Party (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

[3] Aaron Griffith, God’s Law and Order: The Politics of Punishment in Evangelical America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2021).

[4] Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 10.