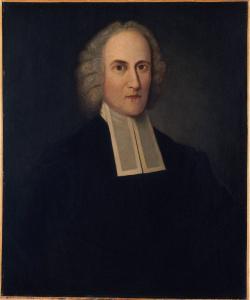

Jonathan Edwards was one of the most significant pastors and theologians in American religious history. He also enslaved other human beings.

I’m no expert on Edwards, but I don’t think there’s anything new or controversial about either claim. Both are evident, for example, from George Marsden’s magisterial biography, published almost twenty years ago. (If I mess up what follows, perhaps we can talk him into coming back to the Bench to correct me!)

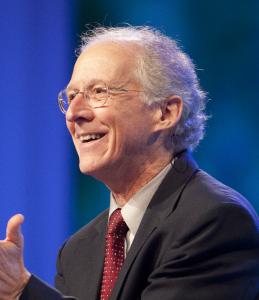

But Edwards’ slaveholding is back in the news because one of his best-known contemporary admirers, John Piper, wrote a controversial essay about it earlier this month at his Desiring God site.

It’s not the first time Piper has addressed this troubling dimension of one of his theological heroes. In 2013, he recorded a seven-minute interview about Edwards and slavery for the same website. On that occasion he offered some wise pastoral advice that seems generally pertinent for Christians as they study church history. For example, Edwards’ slaveholding warned Piper “not to idolize or idealize any man except Jesus. Something is going to show up and disillusion me if I pick out a dead man or a living man as somebody that I am going to idealize. There is no ideal man — except Jesus.” And Piper recognized that if Edwards “had blind spots on that issue, he may well have had blind spots on other issues, which means that I am going to read with some more care.”

In 2013 Piper declined to try to explain why Edwards owned slaves, or to consider how he treated them. By contrast, last week’s essay was entitled, “How Could Jonathan Edwards Own Slaves?”, a question that leads Piper to a troubling conclusion.

He suggests that Edwards and his wife Sarah may have “used their upper-class privileges (including the power to purchase slaves) for beneficent purposes toward at-risk black children.” He thinks it possible that Edwards bought a teenaged girl named Venus (in Newport, Rhode Island in 1731) in order “to rescue her from abuse,” and later purchased a younger boy named Titus (named in the estate inventory at Edwards’ death in 1758) to give him “hope.”

So slavery, as Piper hopes Edwards participated in it, was not so much a malicious system of exploitation, held in place by violence and the threat of the same, but what Christianity had rendered “a shell — a social structure whose inner reality was radically new. So much so that within this community, even if labels persisted, the structure was not what it once was. It was no longer property-owner slavery.”

I can’t believe that Piper doesn’t realize that his speculation about the “beneficent” intentions of Edwards the slave owner sounds uncomfortably similar to the Lost Cause myth of kindly Christian plantation masters exerting a benign empire over grateful charges. He does allow that it could come off as “wishful thinking”:

I do not wish for one of my heroes to be more tarnished than he already is. But perhaps it is not just wishful thinking. My wishes are not baseless, however unlikely they may seem against the backdrop of mid-eighteenth-century attitudes. All I know of the godliness that Edwards taught, and in so many ways modeled, inclines me to wish in just this way. It is the sort of dream that, if it came true, would not surprise me.

I understand the appeal of historical wishfulness. Even when we know that we ought not idolize any fellow sinner, we find people to admire in the past, people whose actions inspire us and whose ideas influence our own thinking. It’s tempting to minimize their shortcomings in one realm lest those weaknesses threaten what we’ve built up around other aspects of their life and thought.

But wishful thinking is not historical thinking. And the former can obstruct the latter.

Since “we have almost no direct evidence of [Edwards’] attitude and action toward his slaves,” Piper concedes, “[t]he scope of what we do not know is very great.” But we do know that Jonathan Edwards, though conflicted in his views on slavery and (more so) the slave trade, ultimately drew on his considerable abilities as a theologian and philosopher to justify a dehumanizing system to which he could envision no alternative on this side of the millennium. (If you have access to the Journal of American History, see Kenneth Minkema’s 1997 article on Edwards and slavery, cited by Piper.)

As Piper’s allusion to “the background of mid-eighteenth century attitudes” suggests, slavery was part and parcel of the white Christian culture of Edwards’ America. He grew up around slavery, the son of slaveowner in a New England culture that expected even clergymen like Timothy Edwards to own other human beings. (Timothy pastored a church in Connecticut, where half of ministers owned at least one slave as late as 1790.) Christian apologies for slavery cut across theological divides in that age of evangelical awakenings. As a Pietist, I need to grapple with Nikolaus von Zinzendorf telling black Christians on the island of St. Thomas that “God has punished the first Negroes with slavery. The blessed state of your souls does not make your bodies accordingly free, but it does remove all evil thoughts, deceit, laziness, faithlessness, and everything that makes your condition of slavery burdensome. For our Lord Jesus himself was a laborer for as long as he stayed in this world.”

Quoting this 1739 sermon, historian Jon Sensbach refuses to wish away Zinzendorf’s statement as nothing more than an awkward concession to a governor nervous that Moravian missions would cause a social revolution. “In previous writings,” Sensbach notes, Zinzendorf “was firmly on record as endorsing a divine social hierarchy, in which he had no trouble including slavery, and he fully agreed that the enslaved had no business seeking liberation.” I’ll come back to it before we’re done, but let me briefly underline the importance of 18th century white Christians like Edwards and Zinzendorf seeing slavery in terms of a larger belief in the rightness of God-ordained hierarchy. “We can consider Edwards’ attitudes toward slavery in the context of his hierarchical assumptions,” George Marsden began his discussion of that topic. “Nothing separates the early eighteenth-century world from the twenty-first century more than this issue.”

But not everyone in the 1700s shared such assumptions. Precisely because they were so common, it’s all the more important to recognize those few Christians who refused to conform to the pattern of their enslaving world — and that Edwards was not one of them.

That list has to start with enslaved Africans themselves. If we know relatively little about Jonathan Edwards’ motivations for owning fellow human beings, we know far less about the experience of people like Venus and Titus. But it’s surely not wishful thinking to imagine that they would have preferred to make free decisions about their lives and to receive fair compensation for their labor.

Among white Christians, what Marsden calls “the first widespread revolution in attitudes” about slavery came after Edwards’ death in 1758. But some public questioning of “the unusual inequities of African slavery” had been heard for decades. Edwards was probably unaware of the first petition against slavery in North America, since it was drafted fifteen years before his birth by an obscure group of German immigrants to Pennsylvania. But he may have known an antislavery tract called The Selling of Joseph (1700), since it was published by a Boston judge named Samuel Sewall, a friend of Edwards’ maternal grandfather. Much of what we know about Edwards’ attitudes on slavery comes from an episode in 1741, when he defended another pastor whose parishioners criticized him for owning slaves (among other grievances). And it’s impossible to write about Edwards’ slaveholding without noting that he was born in the same year as another leader of the First Great Awakening: John Wesley, whose abhorrence of slavery requires no wishful thinking at all.

https://twitter.com/drantbradley/status/1428819270587256834

(While Wesley’s most fiery condemnations of trafficking and slaveholding came later in his life, as an abolitionist movement gathered in England, church historian Irv Brendlinger found antislavery to be a consistent theme in that theologian’s life: “While he does not attack slavery head on until he is sixty-nine years old, he has numerous interactions with the topic throughout his life and not once does he speak favorably about it. When he does confront slavery, he leaves no doubt about his position. He gives no evidence that his position has changed and he continues to work to end slavery until his death, nineteen years later.”)

In short, it was very difficult but not impossible for an 18th century white Christian to see slavery as an unnecessary evil. Not to say that I’d have done any better than Edwards on this count, but he could have joined those few others in rejecting the values of slavery, opting out of its economy, or even seeking its abolition. Not in spite of Christian faith, but because of it. “There is a saying,” wrote the Germantown antislavery petitioners in 1688, “that we shall do to all men like as we will be done ourselves [Matt 7:12]; making no difference of what generation, descent or Colour they are.” Seventy years later, the annual meeting of Philadelphia’s Quakers took an official stance against slavery, in the same year that Edwards died.

Edwards did seem to endorse the spiritual equality of all people, regardless of “generation, descent, or Colour.” Marsden reports that Edwards accepted black and Native American members to his church in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Piper adds Edwards’ comment that master and servant “both have one Maker, and that their Maker made ’em alike with the same nature.” His own son and others of his followers later supported abolitionism; “in the logic of Edwards’s ethics and epistemology,” Piper argues, “seeds of a unique antislavery ideology would be planted.”

But “true to his hierarchical instincts,” concludes Marsden, “Edwards pulled back from any politically disruptive implications of this evangelical Christian egalitarianism.” It’s the lingering power of those instincts — and Piper’s own pulling back from another disruptively egalitarian implication of Christianity — that kept coming to mind as I read his essay on Edwards.

Race-based chattel slavery has been confined to history’s dust heap, and Piper has made clear that he rejects the superiority of one race to another. But other “hierarchical instincts” endure, inspiring other unequal systems whose supposed beneficence Christians like Piper struggle to defend.

For example, I’m convinced by scholars like our own Beth Barr and Kristin Du Mez that it is a hierarchical instinct that principally inspires Christian patriarchy — whether in the 18th century or the 21st. I don’t know John Piper’s writing and preaching well enough to know how much his complementarian understanding of gender roles depends on the life and teaching of Jonathan Edwards. But I don’t think it’s unfair to add one more observation from George Marsden: that Edwards grew up in a family that not only held at least one slave, but held his mother, Esther, as “a subordinate in Timothy Edwards’ household. For Puritans, as for almost everyone else, the axiom that the world was hierarchical was as unquestionable as that the sun rose in the east. Fathers were the heads of their households and their rule was law.” Divinely ordained hierarchy — whether of race or gender — was not incidental to Edwards’ worldview.

The white supremacist version of that axiom is now so objectionable that John Piper can’t help but wish for a better version of his theological hero. But the rule of men remains “unquestionable” in too many churches. Under the power of those “hierarchical instincts,” too few Christians who affirm an intellectual idea of spiritual equality translate it into social experience. And too many Christians continue to cast oppression as a mere “shell” encasing supposed kindness, continuing to assume the best intentions of the powerful rather than simply empathizing with the powerless and condemning unreservedly the abuse they have suffered.

As a postscript… I am not a Reformed evangelical, and it’s evident that I disagree strongly with John Piper on many points. But if you want to read a stronger critique of Edwards from someone closer in theology to Piper, try this 2019 lament by Jason Meyer, who succeeded Piper as preaching pastor at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis. Of course, Meyer has been in the news this summer because he resigned that position, part of a complicated controversy that involves disputes about racial justice and how church leaders dealt with allegations of abuse.