Writing under the name “William Penn” in 1829, Jeremiah Evarts penned a series of essays eviscerating the United States government and comparing Andrew Jackson to Ahab, a wicked king of Israel from the Hebrew Bible. Just as Ahab was held liable for the murder of Naboth after stealing his vineyard, Evarts saw his nation on the brink of a similar crime on a grander scale. As the United States congress considered the Indian Removal Act, Evarts believed they were countenancing an unprecedented crime. He saw Native Americans poised as the prophet Elisha, warning of God’s judgement should the crime occur. How did a boy from rural Vermont, the first in his family to attend college come to such radical views, and what can his journey tell us about the Edwardsian saga in the Early Republic?

Jeremiah Evarts has been largely forgotten aside from a few references in histories of missions and Indian removal. In this paper, I will argue that reevaluating his career, theology, and networks of correspondence assist scholars in making sense of social activism and its theological origins in the early National period of the American Republic. I argue this theological origin comes in the form of an Edwardsian logic I describe as “empathy of encounter.” At least in this sphere, it is common knowledge that Edwards valued embodied experience over disembodied rational principles. I believe this is one of the most important beliefs carried down through the intellectual and spiritual gene pool to his “descendants” less a codified belief system than an embodied logic of experience. None of this made him perfect, but it does cause him to stand out among his contemporaries as a remarkable figure, too long ignored.

Thus, we will travel first through Evarts’ early life until his decision to work for a missionary magazine, The Panoplist. Here we will disembark from the chronological story in order to make sense of the Edwardsean theological world which Jeremiah Evarts inhabited. Having taken our bearings with Evarts’ spiritual compass, we will proceed to make sense of how his lived experiences and theology led him through the various social causes of his day.

Evarts’ parents had chosen just before his birth to move from Connecticut to Vermont. It was here in the small village of Sunderland that Jeremiah Evarts was born on February 3, 1781. Despite hopes that this move would lead to flourishing, the family would struggle financially until after the death of both parents. In October of 1798, Jeremiah Evarts matriculated at Yale University.

New Haven and Yale in the final years of the eighteenth century were presided over by the immense figure of Timothy Dwight IV. The grandson of Jonathan Edwards on his mother’s side, Dwight was a formidable figure in both the religious and political affairs of the entire state of Connecticut. Besides being president of Yale (which required him to be ordained as a congregational minister) he was the acknowledged head of the Federalist party in the state. This led to his enemies referring to him as “Pope Dwight,” for he carried the sword of both god and the state’s wrath. Dwight’s influence over Evarts cannot be overstated. Suffice it to say for the moment that Dwight’s Yale was one in which he knew each student and worked to shape them alongside his cabal of Federalist Edwardseans on the faculty of Yale.

Evarts was already showing signs of future social and theological concerns during his collegiate career. In addition to his school work, he joined the Philencration Society in order to debate with fellow students. As a sophomore, he argued before the society in a debate over the role of amor patriae or love of country. Evarts declared that this love was a marker of civilization and by way of an example described how Native Americans would not be parted from “the bones of their fathers.” This particular phrase would be reused throughout his career in defense of Indigenous rights.

Evarts had a radical, religious conversion experience while a student at Yale. His contemporary, Noah Porter described a remarkable “change in individuals, and in the general aspect of the college” during their junior year. It had such an effect upon Evarts, that he wrote a covenant with his class proclaiming that they would “pray for each other, to learn one another’s circumstances, and to correspond with, and counsel one another in subsequent life.” This moment would guide Evarts across the next thirty years of his life, with his correspondence often referring to it in Biblical terms as a memorial stone. One might expect that such an experience would have propelled the young New Englander to become a minister as so many promising young men of his region had before him. Indeed, his friends and mentors alike seemed surprised that he never appeared to even consider becoming ordained.

After teaching at a rural Vermont school for a year, he announced his intention to study the law. One motivating factor might have been that nearly as soon as he had a steady job after Yale, consistent requests to send money home began to arrive from his parents. He always obliged. From teaching, he turned to law. As he considered his prospects, Evarts wrote to a friend that “If it is not right for a good man to study law… the law must be given up as a… collection of harpies polluting everything by their impure touch.”

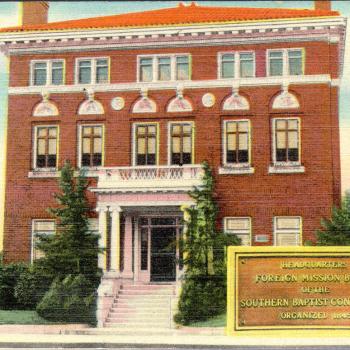

Soon after finishing his training as a lawyer though, he moved his young family to Boston and began working for the Panoplist an independent magazine loosely affiliated with the foreign mission movement as embodied in the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Despite not working actively in any “mission field,” many of his correspondents refer to him as a missionary because of his work on behalf of and then for the ABCFM. Here then was Jeremiah Evarts in 1805. A trained lawyer driven by religious experiences to begin his tenure as a magazine editor in the intellectual hub of the young United States.

This proves an apt moment pause from Evarts’s chronological story. In order to understand both his vocational and intellectual choices, it will be useful to understand the theological—and by extension, political world—Evarts inhabited. While his Federalist and Edwardsean sympathies have already been alluded to, we should ascertain what these terms meant particularly for Evarts. His intellectual world was oriented with Jonathan Edwards as polestar. However, in order to truly make sense of the means by which he inherited Edwards’s though and what particularly he received from that tradition, we must begin with a publishing puzzle. In an April 1812 edition of the Panoplist, Evarts published a small articled headlined “A Relic of Mrs. Edwards.” By way of a description, the article was headed with these lines “THE following paragraphs are extracted, with a few verbal alterations, from a paper in the hand-writing of Mrs. Sarah Edwards, wife of the illustrious President Edwards, dated Oct. 22, 1735.” It was not until 2019 that scholars were able to read the document to which Evarts alludes. And though his editorial hand was quite heavy, the piece appears to have been drawn from the diary of Sarah Pierpont Edwards, the wife of Jonathan. This raises several questions which may help us make better sense of Jeremiah Evarts relation to the broader Edwards family and the Edwardsean theological tradition. Evarts must have been in close relationship with the Edwards family (most likely through the Dwights) to be offered some form or copy of the text.

Additionally, the sorts of experiences Evarts edited out are similar to those which seem be part of why Jonathan carefully avoided any distinguishing details when he told a version of Sarah’s experiences in his Faithful Narrative. He was attempting to protect his wife from critical, prying eyes while using her example as the preeminent experiencer of the Awakening to defend its spiritual veracity. Edwards’s reaction to embodied religious knowledge was to see it as a possible location of divine presence and encounter. I will refer to Edwards’s theological and pastoral reaction to and interpretation of these experiences as an empathy of encounter. An empathy that seems to have reached Evarts.

Evarts learned a form of Edwards’s theology via his students Nathaniel Taylor and Jedidiah Morse as well as Edwards’s grandson Timothy Dwight IV. Each of these three men wrote letters of reference for Evarts upon his graduation from Yale. Almost none of these Edwardseans under whom Evarts studied were recognizably Calvinist. They lacked an emphasis on covenant theologies, did not believe in predestination, and emphasized humanity’s freedom in salvific matters. Michael P. Young calls this phenomenon among the New Divinity an “affectionate recasting of Calvinism.” Despite this, they all considered themselves to be heirs and spirituals descendants of “President Edwards” as he was usually named in their writings.

This then raises the question of how they might properly be understood in the lineage of Jonathan Edwards. I argue that empathy of encounter seems to be primarily what the New England Edwardseans inherited from their teacher. This argument can be understood under the umbrella of what I call—borrowing from and modifying Derrida—a logic of experience. Jacques Derrida provides a helpful framework for considering just such an uncanny conservation of a tradition. Writing about Nelson Mandela’s unexpected use of the Western tradition, he argues “You can recognize an authentic inheritor in one who conserves and reproduces, but also in one who respects the logic of the legacy enough to turn it upon occasion against those who claim to be its guardians, enough to reveal, despite and against the usurpers, what has never yet been seen in the inheritance.” What Derrida calls a logic of legacy; I see performed as a logic of experience by those in the Early Republic who sought to follow the example—if not the particular beliefs of Edwards. This concept helps us make sense of an essay by Mark Noll articulating the different strands of Edwardsean inheritance after Edwards’s death. Noll comments that perhaps Edwards’s greatest legacy was the manner in which he “preached eagerly for conversion…experimented with new methods for revival, and… depended manifestly upon the power of God to change people’s lives.” Indeed, this appears to be how Evarts received Edwards’s legacy. Evarts’ surprising activism grows out of this evangelical mode—an emphasis on conversion, revival, and the power of God—that he inherits from Edwards. We can see this by observing that in addition to the “Relic of Mrs. Edwards” he published at least two other essays about Jonathan Edwards. One was a dissection of Edwards’s resolutions and how they might serve as a model of virtue for those considering the mission field. The other was an exposition on Edwards’s mode of preaching.

Just as Edwards’s experience with Sarah led him to be more sympathetic and open to embodied forms of religious knowledge, encounters with free blacks for Samuel Hopkins and Opukaha’ia—a Native Hawai’ian man—for Jedidiah Morse and Timothy Dwight galvanized them to action in their own ways. For Samuel Hopkins, this encounter shaped his becoming a radical abolitionist: calling for the immediate, uncompensated freedom and citizenship of all enslaved peoples. For Jedidiah Morse and Samuel Worchester, it meant helping to form the American Board of Commissioners in order to reach the heathen with the gospel. Each of these examples was precipitated by encounters with an other. As we will see, Evarts’s had several such encounters that together led him to his constellation of activisms.

In addition to foreign missions, the ABCFM had a secondary goal to send missionaries to Native Americans. It was under this angle of the ABCFM’s mission that Morse and Dwight along with other supporters began a school “For the Education of the Heathen,” in Cornwall, Connecticut. The initial pupil was a previously mentioned Indigenous Hawaiian man. Timothy Dwight, had met Obookiah and determined that such a school should created under the auspices of the broader missionary effort. Evarts coordinated fundraising for the school as well as assisting in discovering pupils and teachers. Although he does not mention any particular scholars whom he met during his 1814 and 1817 journeys through the southern missions, it is difficult not to imagine that he had already come across the young John Ridge and Buck Watie at the Brainerd Mission School in the Cherokee homeland. Not only would they become the most famous students of the Cornwall school, but they both developed firm friendships with Evarts. When a controversy broke out in 1824 regarding whether Native men should be allowed to marry white women, Evarts led the charge in championing the Cornwall students.

Amidst the 1824-26 controversy over interracial marriage at the Cornwall Foreign Mission School, Evarts took on a nom de plume to argue in favor of interracial marriage. Under the name William Crawford, he argued that no individual could be “bound to act in accordance with the public will if that will is wrong.” He took an even stronger tone when writing to his fellows on the missionary board: “Can it be pretended at this age of the world, that a small variance of complexion is to present an insuperable barrier to matrimonial connexions[sic], or that the different tribes of men are to be kept forever & entirely distinct?” He enquired in the same letter why any Native American would take seriously calls for entry into the Christian faith when doing so proved no advantage against the violence and ravages of supposedly Christian governments. Evarts did not only argue for this flavor of equality in a theoretical sense though. He supported Elias—formerly Buck Watie—Boudinot and Harriet Gold’s engagement and ultimately helped sway her parents to support the union. When the marriage occurred, he was the only guest present besides her parents and the minister. Thus, Evarts’s attention to Native rights can be understood to grow out of his missionary fervor and empathetic encounters with the Cherokee.

To the extent that Evarts has been remembered, it has largely been because of a series of essays he wrote under the pen name William Penn. These twenty-four essays published and then syndicated in early 1829 provide a foundation for making sense of the forgotten movement that worked to prevent Indian Removal. Claudio Saunt has argued convincingly that in the Penn essays Evarts followed the lead of Cherokee authors including David Brown and Elias Boudinot. Following their arguments in pamphlets and the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, Evarts worked to amplify the Cherokee perspective to a broader Euro-American audience. It is in these Penn essays that Evarts makes the powerful argument I described at the beginning of this paper, comparing Andrew Jackson and the American government to Ahab and Jezebel.

Edwards and Evarts share in being controversial regarding slavery and abolition. In a letter from 1826, William Lloyd Garrison complained to a friend that although Evarts was the most prominent activist in the country and clearly cared about the rights of non-white peoples, he had not come out publicly in support of abolition. This frustration must have run deep for Garrison. When he first set out to publish The Liberator, which would become one of the most important voices of the abolitionist movement, he came to Evarts for advice on running a newspaper which would advocate for unpopular social causes. Despite this, Evarts had been at least privately an advocate of abolition since 1817. In a letter to his wife from that year, Evarts described observing a slave auction in Savannah during a trip to the South. His reflections include a piercing analysis of the experience. “It was a humiliating spectacle to see a human being put up with damaged cheese, shoes, etc. to be disposed of for life to any man who might purchase him.” He continues, “my children might be taken and sold with as much justice and propriety as the immense multitude of the Native Africans.” This experience at a slave auction served as an empathetic encounter. Additionally, he corresponded with many of the leading abolitionists in the anglophone world. At least one scholar reads the secondary literature as describing Evarts as an anti-abolitionist despite his personal distaste for slavery. However, the secondary literature cited is by no means clear on the point. Nor does Evarts provide any evidence in his writings for being anti-abolitionist. It is clear that he refused to take a public stance on the issue. However, his consistent correspondence with abolitionists abroad, as well as his aid to domestic activists seems to indicate that he may have held stronger views than he felt could be safely acknowledge publicly.

There are at least two explanations for Evarts’s reticence to publicly call for abolition. The first is that his priority was defending Indigenous rights and the forward momentum of the missionary movement. Both these causes would have been adversely affected by a key spokesperson proclaiming the gospel of immediate abolition. The second is perhaps more mercenary hand regards fundraising for the ABCFM. Both the Panoplist and the ABCFM were constantly struggling for funds, and as we have discussed, Evarts often sent money to his parents. Much of Evarts’s correspondence to missionaries abroad was begging for patience as he raised more money. Publicly espousing abolition would have done nothing to help this fundraising problem and would only have made it significantly worse. It is important to recall just how unpopular and marginalized the abolitionist perspective was in the Early Republic.

The work on behalf of Indian rights also provided a remarkable degree of indirect support for free African Americans. A group in Providence, Rhode Island wrote a public letter noting the strange distinction made by many white New Englanders. These allies railed against Cherokee removal while advocating for resettling freed slaves in Liberia. As Natalie Joy describes, although “it failed to convert many northern white reformers to immediatism, the antiremoval movement helped black and white abolitionists develop more radical arguments against colonization.”

Evarts was a remarkably intelligent man; he was keenly aware of hypocrisies in his countrymen’s feeling and thought. Particularly given his relationship with Garrison, it seems unlikely he was unaware of how his position appeared. I believe this was because as mentioned for Evarts above, such a declaration would have only furthered their isolation and obstructed any possibility of halting Indian removal.

How did Evarts story end? Well, he had always been sickly. And Indian removal did occur. All the petitions and essays and letters failed. The Indian Removal Act finally passed Congress in late spring 1830, and Evarts died a few short weeks later, many said from a broken heart, disappointed in his countrymen. And yet. The methods of activism pursued by Evarts and his network came to be a model and a signpost for later activists both of how hard one could strive and still lose, but also of potential methodological frameworks for nationwide activism. This was particularly true for the mobilization of young women and the presentation of petitions before Congress. History is never a fairy tale, and while it may seem strange to point to a radical failure as the origin of American social activism, it speaks to the ironies of its Edwardsean genesis.