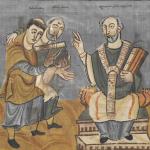

In 1789 a sailor who had been enslaved, bought his freedom, and become part of the abolitionist movement penned his autobiography: The Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African. This was a very effective campaign tactic for the abolition movement and for convincing the English-speaking Atlantic that the slave trade was cruel and should be abandoned. Equiano was an evangelical Christian as well, and the book functions as a spiritual autobiography in which he traces the ways that God brought him through the challenges of his life.

It may also contain falsification of his life story. The earliest parts of Equiano’s life are unverifiable as his own experience, specifically his life in West Africa before being brought to the Americas via the horrific Middle Passage. Scholars recognize the accuracy of the cultural and linguistic evidence he provides for the Igbo context, but without records of who was bought and sold, we are unable to trace text-based evidence for Equiano before his late childhood in the Carolinas. It is possible that he was born in Carolina and used the experience of someone he met by integrating it into the story as his own childhood kidnapping and forced shipment to the Caribbean.

My students are obsessed with this element of the book. They ask: How can we trust this story if it isn’t true? How can we prove one way or another if it’s accurate?

Historians believe the stories about the past that we investigate are true. While we often study stories that overlap with literature, and while we appreciate stories that represent Truth without being depictions of something that happened, we are doing something different. We want some element of accuracy, and our research is an attempt to be honest about the evidence without throwing up our hands to say since we can’t know everything in all detail we might as well write fiction.

The Life of Olaudah Equiano is a great example of this challenge and what might be at stake in deciding how true something is. If we feel we can learn important truths about slavery from fiction (in the USA it was famously the fictional novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin that contributed to changing minds and hearts about slavery), why does it feel like it undermines the power of a memoir if it partly fictional?

I think it is more than that memoirs with false information undermine the entire credibility of the author. It is true that sometimes non-fiction writers with an agenda have been undermined when some of their stories were demonstrated to be fabrications. For instance, questions about Greg Mortenson’s accounts in Three Cups of Tea damaged his attempt to help students in Pakistan and Afghanistan. But this was only after there were already concerns about his charity organization. Perhaps if no one had become concerned with the reliability of his mission, they would have had less concerned about the factual accuracy. And even after all these years, his story is still read as a way to inspire people to think more positively about central Asia and to be more generous with folks far away.

Sarah Viren’s To Name A Bigger Lie is a recent memoir that plays with the interaction between memory, history, and deliberate falsehood. In writing her story, she frontlines the work she did to verify her memories, and her discovery of when she was wrong about how she thought about the past is part of the story. But she also highlights how sometimes the most important truths aren’t things that can be verified beyond a reasonable doubt and are still “True” even if they can’t be established in some scholarly way.

This is why people appreciate fiction or other forms of non-history as a way of getting people to engage with the past or to learn about something and then care about it. Even fictionalized or novelized versions of historical people like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series can go much further to engage readers than the non-fiction version. Creative story telling touches our hearts and elevates the Truth about humans and right and wrong, courage and love, pain and abuse. Readers feel they can understand the people in the past why what happened was so important when they read a novel.

And yet, we want to know that these things also are true and “really happened” in the historical and scholarly sense. I can’t begin to number the people who have told me (a historian!) that a novel they read was “really historically researched and is very accurate” as part of saying what they enjoyed about it. Even though they want to connect with the past and feel that something reflects larger and important Truths, they want that rooted in the more mundane elements of facts and verifiability.

We want our Truths to also be true. Stories that are trying to get us to change our minds and hearts are doing so based on the fact that they have veracity, even if it is at arm’s length. It is possible that young people who are being so influenced by science fiction and fantasy writing over the past couple decades may not care so much in the future about whether the stories that shape them have any sort of accuracy, but in the meantime stories that are rooted in the reality of Earth as it is now still have primacy in social justice or other motivational movements.

This is where the work of the Historian is so valuable. Sometimes our writing isn’t as compelling as that of a novelist, but our work is important because for people who want to do things in the world, who want to be active citizens or understand society—facts and data about what has happened are foundational. We do the grunt work for folks who can create characters to represent the past and engage readers. Occasionally we even write well enough to reel in casual readers—who then become sympathetic actors in their society. Journalist Isabel Wilkerson’s Warmth of Other Suns relied on much of the scholarship of historians to write important non-fiction that effectively explained the Great Migration and its impact for a much wider audience than had professional academic writing over the last fifty years. But it couldn’t have happened without the groundwork of scholars.

For Christians especially, we find it vital that the Story that shapes us is rooted in a historical past. Perhaps the important Truths of God’s love and forgiveness can be discovered without an understanding of characters and events that are rooted in real times and places. And it is true that some of Scripture’s events and people are more discoverable than are others, but there is a reason that Christian history is the industry that it is. Our faith is supported by historical actors and events rooted in real place and time in a way that many other religious expressions are not. We often ask “Did this really happen?” Our faith is firm in spite of our lack of data. But we still work towards more historical understanding—not only of what happened in Scripture, but throughout the last 2000 years of Christian experience. We are tied to those who came before and we believe more accurate information allows us to do better in the future.

Olaudah Equiano’s compelling narrative was based on his own experience as an African who had made the crossing and then told the story in a language understandable to Englishmen, demonstrating in his own body and words that Africans were sophisticated and not dependent on Europeans for practices of morality and cultural complexity. He compared European practices of enslavement with African ones and found them wanting. While a Christian, he rejected the idea that the Atlantic slave trade was necessary for Christianity to reach West Africans.

If Equiano’s story is not totally his own, it definitely made such an argument weaker for his audience at the time. And yet all the details of life in Africa and the Middle Passage have been revealed to be accurate and his overall point is valid, so historians continue to depend on his account as a reliable source of information. When my students ask me why we should read this as history when some of it may not be true, we get to explore the why truth matters and why fiction has a different role from historical evidence. They get to form their own conclusions about when and how they are comfortable with Truth that is formed through story and metaphor and when they want truths that are based on data. I am thankful that there are multiple ways of knowing and that my students can benefit from all of them, even as my profession will continue to do the work of data-gathering about the past.