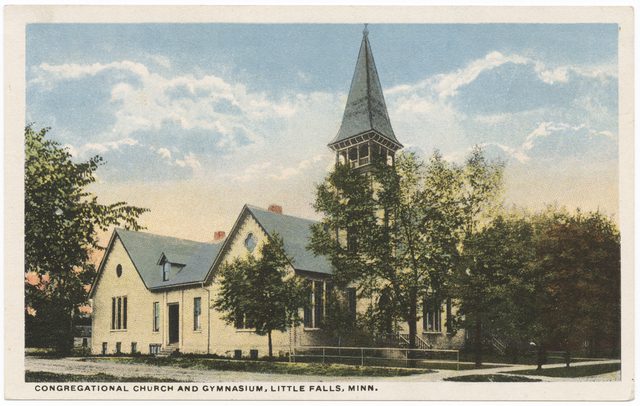

I’ve never liked reading especially long biographies myself, so I’m happy to report that my version of Charles Lindbergh’s life — officially out one week from today! — requires just over 200 pages of your time. Given that number, you may be surprised to find that I dedicated the better part of two pages to a church that Charles Lindbergh didn’t attend.

At least one other Lindbergh biographer has mistakenly assumed that a Swedish American family would naturally go to the Swedish Lutheran church in Little Falls, Minnesota, a town whose population of such immigrants was growing rapidly around 1900. But to the extent that C.A., Evangeline, and young Charles Lindbergh participated in the life of any religious community, it was First Congregational, not Bethel Lutheran.

“Of the many possible reasons for that choice,” I write, “the most practical is the most likely”: the people of Bethel Lutheran worshipped in a language that the Lindberghs didn’t understand.

C.A., who was an infant when his parents left Sweden, had no more than a rudimentary knowledge of Swedish. (Incidentally, August and Louisa Lindbergh took C.A. and his siblings to an Episcopal church). Charles, like his mother, spoke only English.

To understand just how unusual the Lindberghs were in this respect, I thought it would be helpful for readers to know that Swedish

remained the language of worship at Bethel Lutheran throughout Charles’ childhood and youth. It wasn’t until World War I… that the church finally added English services two evenings each month. Bethel Lutheran didn’t complete the transition to English until the beginning of the Second World War, when the church called its first American-born pastor. It wasn’t just the Swedes; even First English Lutheran Church of Little Falls didn’t stop using Norwegian until 1926.

For that matter, my university began life — 150 years ago this fall — as a Swedish Baptist seminary that didn’t make English its language of instruction until the end of the Twenties. Writing in 1929, Richard Niebuhr emphasized the role of language in making “many an immigrant church” into “more a racial and cultural than a religious institution in the New World,” where “in many a pulpit the duty of loyalty to the old language was almost as frequent a theme as the duty of loyalty to the old faith.”

So the fact that the Lindberghs chose an English- rather than Swedish-speaking church in the first decade of the 20th century underscores just how thoroughly they had assimilated into Anglophone America.

Still, it seemed like four paragraphs on Bethel Lutheran Church was enough to make my point, so I confined one element of its history to the phrase that I replaced with ellipses in the block quotation above. Here it is in full, with the missing clause restored in italics:

It wasn’t until World War I—when the use of Swedish, like German, seemed suspicious to a certain kind of patriotic Minnesotan—that the church finally added English services two evenings each month.

I didn’t want to belabor the point in the book, but it seems like a good topic to flesh out in a blog post…

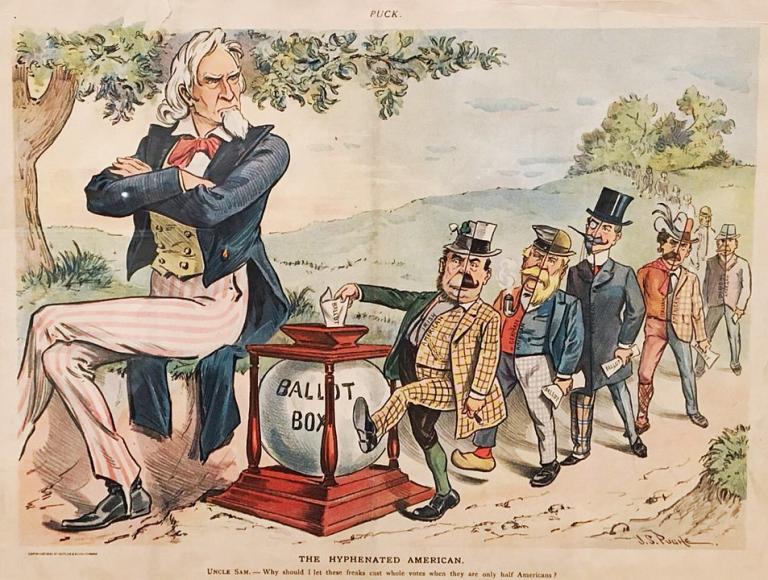

Woodrow Wilson and Teddy Roosevelt didn’t agree on much in the first years of WWI, but they both disdained and distrusted those “hyphenated Americans” who continued to find their identity in the customs and culture of their homelands back in the war-torn Old World. Such immigrants “at heart [felt] more sympathy with Europeans of that nationality, than with the other citizens of the American Republic,” Roosevelt warned the Knights of Columbus on Columbus Day 1915, the same year that Wilson used his State of the Union address to decry those “born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life.”

When the U.S. entered the war two years later, it wasn’t just German Americans whose loyalty was questioned by their xenophobic countrymen. For example, immigrants from neutral, Lutheran Sweden were suspected of being too sympathetic to the homeland of Martin Luther.

Which may help explain why J.A.A. Burnquist, the Swedish American governor of Minnesota — where 70% of the population were immigrants or first-generation Americans, and whose Congressional delegation had split on the vote for declaring war — went out of his way to demonstrate his patriotism. Burnquist headed the state’s Commission of Public Safety, whose legal counsel, Ambrose Tighe, justified its efforts to root out anti-Americanism by appealing to an 1883 public health statute: to Tighe, German Americans constituted a source of “disease.” The commission investigated suspicious figures like the city leaders of New Ulm (including the president of Martin Luther College) and sent agents to disrupt rallies by one of Burnquist’s rivals in the 1918 gubernatorial race: C.A. Lindbergh, who continued to question the reasons for American involvement in the war.

Under Burnquist, Minnesota also became one of twenty states that limited the public use of languages other than English. Newspapers written in other languages were subject to CPS review, German textbooks were censored, and public schools had to teach in English. (The enemy, one University of Minnesota professor told the National Association of Education, planned to undermine the war effort through “German teachers teaching German ideals through the German language.”) Such actions, concluded Nils Hasselmo, “probably had a chilling effect on many who had previously used the immigrant languages both privately and publicly” — those of German ancestry (25% of the state population in 1910), but also Swedes (12%) and other groups.

The CPS refrained from closing the 200+ parochial schools that taught in German, Polish, Norwegian, and other languages, and its English-only teaching regulation never applied to religious instruction. In Minnesota, churches like Bethel Lutheran began to switch to English under pressure, but not coercion.

But in other states in the middle of the country, state regulation of “hyphenate” languages affected religious communities directly. Few municipalities went as far as the Oklahoma county whose version of the public safety commission resolved that since “God Almighty understands the American language, address Him only in that tongue.” But Nebraska’s State Council of Defense first limited non-English teaching in denominational schools, then extended the ban to include sermons and Sunday schools. The council’s efforts didn’t carry the force of law, notes historian Frederick Luebke, but “very few clergymen were willing to risk the wrath of adverse public opinion, which had been so effectively marshalled by the council.”

As in Minnesota, Swedish (plus Danish and Czech) communities in Nebraska were targeted, not just German enclaves. So too in Iowa, where in May 1918 Governor William L. Harding issued the so-called Babel Proclamation, mandating the use of English in all schools (public and private), all public conversations (including those conducted over the telephone), and all public speeches. That included sermons, for while Harding admitted that

Each person is guaranteed freedom to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience… this guaranty does not protect him in the use of a foreign language when he can as well express his thought in English, nor entitle the person who cannot speak or understand the English language to employ a foreign language, when to do so tends, in time of national peril, to create discord among neighbors and citizens, or to disturb the peace and quiet of the community.

Such bans included some accommodations for the nearly 25% of foreign-born adult Americans who could not speak English; in Nebraska, sermons could be summarized briefly in the other language, while Harding allowed such Iowans to worship privately at home. But it was devastating to Christians like the Mission Covenanters who wept “because the Word of God has been taken from them and we are not able to communicate the Gospel in English.”

Here again, Germans were not the only population affected. In Peoria, where James D. Bratt reports that some patriotic Iowans struggled to distinguish between “Dutch” and “Deutsch,” Christian Reformed minister J.J. Weersing was forced out of town and vigilantes burned down his church and its school. In Cedar Rapids, a Czech-speaking Catholic priest organized a protest against the Babel Proclamation a week after it came out. And Rev. C.J.M. Grönlid, the pastor of a Lutheran church near Paint Creek, petitioned Harding through a plaintive letter:

I have preached the Gospel in the Norwegian language exclusively for about 40 years, and now in my old age (63) at once to turn over to English will break up my ministry, and exclude about half of the parish from public worship. I therefore petition you most humbly to be permitted to preach the Gospel and administer the Sacraments in Norwegian, because that is not going to create any strife, distrust, or controversy in the community…. Sir, I have been a Pro-ally since the day the Kaiser declared war and invaded Belgium…. I might defy any community in the State to be more patriotic in spirit and in deed than our Norwegians here, and we are tolerably American in language, except the worship.

Danish Americans, whose homeland Prussia had invaded in 1864, were particularly offended by measures like Harding’s. “A person may be born Denmark and still be a good American citizen, and a dog may be born in America and still be a dog,” wrote Lutheran minister Peder Sørensen Vig, who served as president of Trinity Seminary across the border in Blair, NE. “No language in itself is either loyal or disloyal, but it is the use made of such languages that counts.”

Unmoved by such appeals, Harding left his proclamation in effect until a few weeks after the Armistice of November 1918. The following year, Nebraska extended its ban on non-English teaching (for grades 1-8) into peacetime… and now expanded it to cover religious instruction. German Lutherans and Polish Catholics alike took legal action, and in 1923 the matter made its way onto the docket of the U.S. Supreme Court, which voted 7-2 to overturn the conviction of a Missouri Synod teacher and declare such legislation unconstitutional.