Indexes have been much in my mind of late. If you ever write or publish a book, you will understand just how important they are. Historically, they enjoy a significance that is barely unimaginable to modern people of the Google Age.

In the current London Review of Books, Anthony Grafton has an excellent review of a new book on indexing by Dennis Duncan. The book is entitled, inevitably, Index, A History of the. Duncan traces the history from its earliest times in ancient Alexandria through the emergence of the modern index in the later Middle Ages. It was at that point, for instance, that scholars had the wonderful idea of organizing material according to the alphabet, rather than by some hierarchical system that placed God first, then angels, and so on down. That step was crucial to the organization of information, and to all subsequent scholarly research. To take another point, a true index only became possible with the invention of printing, so that references and names actually did stand in a particular, fixed, and predictable place on a page, the same in every copy of the book. With manuscripts, the exact location shifted with each new copy made by every new scribe. I keep thinking back here to Alan Jacobs’s sage observations about how the technology of book production contributed to shaping faith, and in this case, developing information.

If all this seems trivial or mechanical, then just imagine trying to find information from books of 500 pages without some such apparatus. Most people today never think of such a prospect: type a phrase into Google, and you are away. But horrible as this may be to imagine, there was a time before Google, however increasingly hard that might be to imagine. And moreover, indexes are changing again, and maybe in ways just as fundamental as that shift to the alphabetic. If you are intending to produce a book, let me offer some sage advice about what you might expect.

First, expect the process of book production to be largely or entirely outsourced, very likely to a firm in Southern India. If you are expecting me to complain about this as a betrayal of home-grown American labor and enterprise, you will be disappointed. Those Indian firms, based mainly in southern cities like Chennai (formerly Madras), do an excellent job, and are generally very professional indeed to work with. (The time differences do make real-time personal chats with Tamil Nadu a bit difficult). I am getting an excellent sense of the commercial geography of Chennai, not to mention picking up local in-jokes. I have repeatedly had drummed into me the fact that the locals really do call it Madras, rather than the officially correct and nationalist “Chennai” that they think has been imposed on them.

Second, expect a totally different set up in terms of reviewing and editing your material. Coming as I do from the early Dark Ages, I am used to a sequence of someone copy-editing a manuscript, then I comment on that, then it goes to page proofs, and I comment on that, and then there are final page proofs, and woe betide you if you change anything at that stage. Today, not a bit of it. You will receive copy editing and page proofs at the same time, much to your puzzlement.

All this is different from my long experience, but I can see some good in it. Where I am having real trouble is in the approach to indexing of some producers, by no means all. Some publishers hire professional indexers, who carefully follow all the traditional rules. For instance, an entry should never have more than eight or ten references, and if it does, you had better break it up into lesser subject headings. If you are indexing a book concerning Ronald Reagan, you might have

Reagan, Ronald: early years of; foreign policy of; historical reputation of; presidency of; rhetoric of;

and so on. Compiling such an index is actually a useful scholarly venture in its own right, as it forces you to identify themes and emphases that you had not thought of too much when actually writing the book itself.

But technology does strike. In a recent project, I had completed a manuscript, when the editors asked me to highlight a hundred or so key words in the text. I duly did so, with some puzzlement, and to my mixed horror and admiration, I realized that I was in fact compiling a sort of index. Computers seek out the keywords, and construct them in index format with page references. How does that work? Very well in some areas. I look at my index proofs, and see, for instance, all eight references that occur in the MS to “Thailand”, or all nine to Australia. But “Soviet Union” is disastrous, as the phrase occurs on virtually every page, and the entry as I was offered it reads:

Soviet Union: 2, 3, 4-6, 8, 9-11….

And again, so on, to a couple of hundred entries, that make the index entry quite useless. Obviously, I just pulled that whole entry. Also, quite impossible in that machine-driven format are all those elegant subheadings. If I was applying this technique to a book featuring Ronald Reagan prominently, there would be a couple of hundred page references to that name with no finer distinctions, which would of course be a waste of time and energy.

One of my subject terms was “United States of America,” although through the text, I naturally refer to what “the U.S.” does. The index duly picked up the one full citation of United States of America, and ignored each and every one of the remaining couple of hundred references to “U.S.”

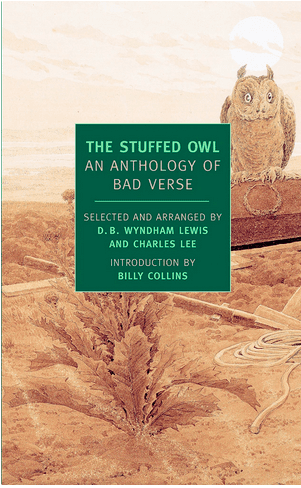

An index, properly constructed, can be a lovesome thing. And that provides me the opportunity to rave about one of the great books of the previous century, and one that still has the capacity to make me laugh hard. In 1930, D.B. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee published a magnificent collection of epically Bad Verse, called The Stuffed Owl. Shockingly for the time, the collection included not just out of the way amateur poetic enthusiasts, but canonical figures like Byron and Wordsworth, Poe and Emerson, in a way that made you realize just how dreadful some of their effusions actually could be.

But the crown jewel of the whole piece is the subject index, which is legendary. I take the following selection more or less at random, each entry duly referring to a poem in the text:

But the crown jewel of the whole piece is the subject index, which is legendary. I take the following selection more or less at random, each entry duly referring to a poem in the text:

Carrot, sluggish, 22

Charles II, his magnetic effect upon the coast line, 31; the Faculty gets to work on, 32

Cheese, Cheshire, by whom digestible, 61

Christians, liable to leak, 4

Cow, attention drawn to, by Tradition, 8

Creation, one vast Exchange, 72; staggers at atheist’s nod, 174

Eggs, mention of, wrapped in elegant obscurity, 62

Eliza, takes the children to see a battle, 106; gets it in the neck, ibid.

Englishman, his heart a rich rough gem that leaps and strikes and glows and yearns, 200-1; sun never sets on his might, 201; thinks well of himself, ibid.

Italy, not recommended to tourists, 125; examples of what goes on there, 204, 219, 221

Mothers, brave men weep at the mention of their, 232

Sheep, British, unhappy in exile, 81; urged by Colin to keep their wool on, ibid. See also Bleaters.

And who can forget

Woman, useful as a protection against lions, 118

With such an index, why bother looking at the text? But one way or another, and even if you proceed back to front, do read the book.