“This is both an important and a frustrating book.”

It was 2009 when I read these words in an academic review–ten years before I would agree to write The Making of Biblical Womanhood; seven years before my husband was fired; five years (give or take) before I realized I no longer believed in complementarianism; and one year after I was hired as an Assistant Professor of History at Baylor University.

It was 2009 when I read these words in an academic review–ten years before I would agree to write The Making of Biblical Womanhood; seven years before my husband was fired; five years (give or take) before I realized I no longer believed in complementarianism; and one year after I was hired as an Assistant Professor of History at Baylor University.

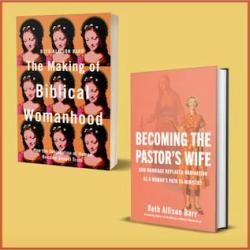

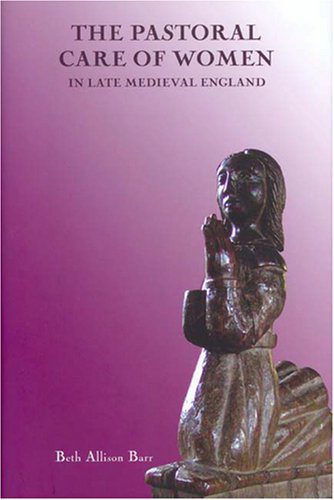

Katherine L. French, one of the foremost scholars in my field, reviewed my first book, The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England, in the academic journal Gender and History (21:1, April 2009). At the time, French was Professor of History at the State University of New York (SUNY)-New Paltz. She is now the J. Frederick Hoffman Professor of History at the University of Michigan, where she also serves as Associate Chair of the History department.

Nine words. That is all Katherine French needed to make her point. I read them over again, uncertain how to react. Should I celebrate?–one of the top scholars in my field had just called my book important. Should I be upset?–one of the top scholars in my field had just called my book frustrating. Her short sentence conveyed so much. It artfully delivered praise while simultaneously levying critique. I took a deep breath and (after emailing my dissertation advisor for support) continued to read.

What I learned made me a better scholar.

First, I learned to trust myself as a historian. The historian I respected most in my field (alongside my dissertation advisor) had just confirmed that my “detailed manuscript analysis” showed what I argued it showed: that a “wide latitude in the use of gender-inclusive language” existed in late medieval English sermons, raising “important questions about the implementation and depth of clerical misogyny.”

As French wrote in my favorite sentence of the review, “With this hard evidence, it is difficult to continue to claim that the clergy had no interest in the pastoral care of women.”

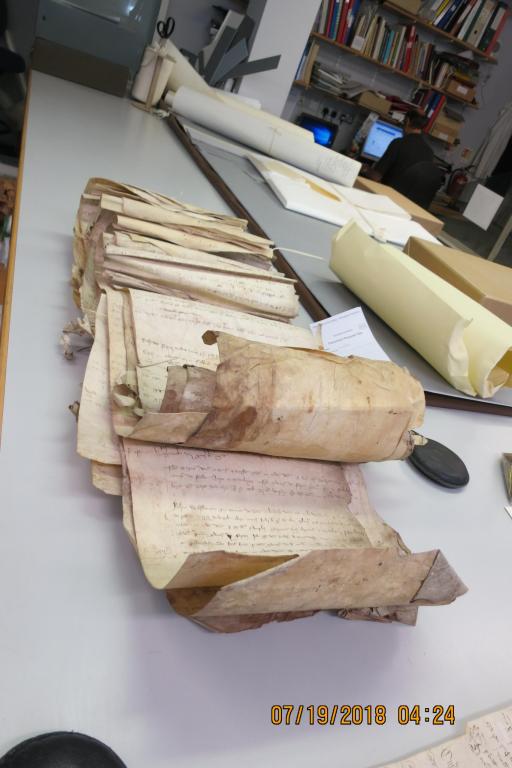

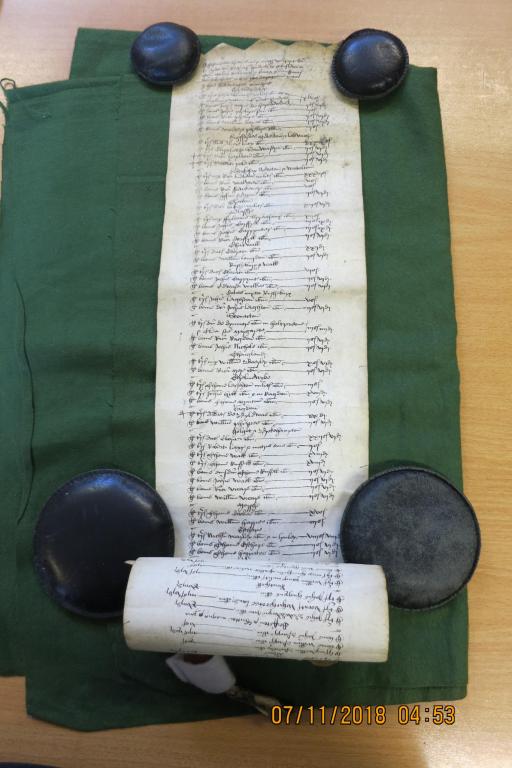

I’m not sure if I can convey the import of that sentence to non-academics. Like so many graduate students, doctoral studies had swallowed my twenties. The last three years of which were completely consumed by research as I tracked down, read, and analyzed the extant manuscripts of one of the most popular vernacular sermon collections in late medieval England. That one sentence by Katherine French validated this hard work. Both my argument and my evidence was sound.

After realizing this (and having the point reinforced by my ever-patient dissertation advisor), I felt better. I hadn’t gotten everything right and I hadn’t done everything that needed to be done, but The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England contributed in a meaningful and important way to the historical conversation. Medieval scholars would have to deal with my thesis.

Second, French’s review taught me to recognize constructive criticism. French charged that The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England did not push the analysis far enough. Failing to balance my focus on sermons and the clerical world that produced them with the wider context of the late medieval parish, I had “not questioned hard enough” how demographic and social upheaval “might have shaped the evolution of pastoral care in the post-plague period.” Most importantly, I had not considered how the “increased parish organization and lay involvement” of the late fourteenth and fifteenth-centuries affected pastoral care.

This criticism did not stem from a turf battle or fear of the implications of my argument. Her goal wasn’t to discredit me in order to plug her own book. She certainly wasn’t attacking me as a person. Katherine French was simply doing what good historians do; what good mentors do. She was pointing out a weakness that limited the impact of my argument.

And it worked.

Her review challenged me to think harder about how the lived experiences of women connected to the sermons produced by clergy. For example, I found that medieval woman like Elena de Zouche served as literary patrons for clergy, commissioning religious texts and even sermons. A century before John Mirk penned Festial, the sermon collection I examined in The Pastoral Care of Women, Robert Gretham (who lived in the same Augustian abbey that would later produce John Mirk) penned a series of devotional sermons for Elena de Zouche. Interestingly, Karen Jambeck has argued that female literary patronage (like that of Elena de Zouche) was often hereditary, with daughters following in the patronage footsteps of their mothers and grandmothers. “Women were capable, serious-minded, and self-aware,” Jambeck writes. “The patterns of patronage that emerge here indicate that they successfully transmitted values and attitudes—among them the tradition of patronage itself—to subsequent generations, especially to matrilineal descendants: daughters, nieces, and granddaughters. In the absence of women’s own words…Their literary patronage establishes their participation in that discourse.”

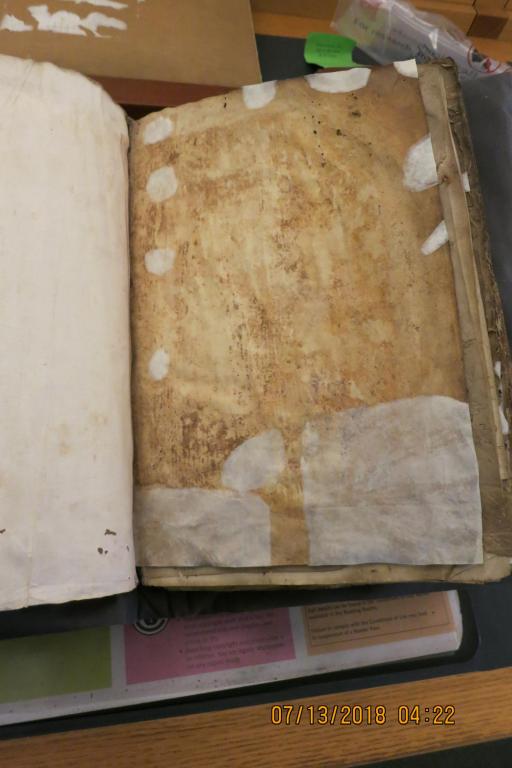

I also began to follow the research of Eliana Corbari. She argued in her 2013 book, Vernacular Theology: Dominican Sermons and Audience in Late Medieval Italy, that sermon manuscripts could be used to determine their audience. As she has written, “the gender of their audience can often be deduced fr om a codicological examination of manuscripts containing written sermons.” Sermons in fifteenth-century Italy were created at the request of women (Coribari found written in the prologues and dedications how women owned and commissioned the texts); they were read and listened to by women (as Corbiari has found women’s notes about sermons and within sermon manuscripts); and they were preserved and passed down among women. Coribari even found that sermons with female-centered narratives received extra attention from their female readers, with women underscoring and commenting in the marginalia. Based on such evidence, she has concluded that “where vernacular written sermons…are found alongside female-centered narratives, it is reasonable to infer that women were their intended readers, and above all, that such texts were particularly well received by female audiences.” Women, in other words, influenced how sermons were written.

om a codicological examination of manuscripts containing written sermons.” Sermons in fifteenth-century Italy were created at the request of women (Coribari found written in the prologues and dedications how women owned and commissioned the texts); they were read and listened to by women (as Corbiari has found women’s notes about sermons and within sermon manuscripts); and they were preserved and passed down among women. Coribari even found that sermons with female-centered narratives received extra attention from their female readers, with women underscoring and commenting in the marginalia. Based on such evidence, she has concluded that “where vernacular written sermons…are found alongside female-centered narratives, it is reasonable to infer that women were their intended readers, and above all, that such texts were particularly well received by female audiences.” Women, in other words, influenced how sermons were written.

The Pastoral Care of Women focused primarily on literary texts and the clerical perspective, but French challenged me to broaden this viewpoint–to include both the context of women’s lives as well as women themselves. I decided to take her advice. I began to develop a new academic book project, Women in Late Medieval English Sermons. It considers both the wider context of the late medieval world as well as how the lives of female parishioners connected with the clergy who produced sermons. While Women in Late Medieval English Sermons will be a follow-up to The Pastoral Care of Women, it is a follow-up directly shaped by the constructive critique of Katherine French.

Almost eleven years after Gender and History published French’s review of The Pastoral Care of Women, Themelios published a review by Kevin DeYoung of my mo st recent book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. I have a lot of thoughts about the tactics Kevin DeYoung used in his review (many of which Michael Bird has addressed better than I ever could). But, mostly, I can’t help but compare his review with that of Katherine French. Both were critical of my work. But only one contained substantive critique that challenged me to be better.

st recent book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. I have a lot of thoughts about the tactics Kevin DeYoung used in his review (many of which Michael Bird has addressed better than I ever could). But, mostly, I can’t help but compare his review with that of Katherine French. Both were critical of my work. But only one contained substantive critique that challenged me to be better.

Stay tuned for my part 2 of this response to Kevin DeYoung (coming either October 7 or October 14). All of the non-book images stem from my manuscript research for Women in Late Medieval English Sermons. There is also a lovely image of medieval rooftops in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, the geographic center for my research. I took the picture from my hotel window a few years ago.