“What if you are wrong?”

Beth poses that question to complementarian evangelicals in her bestselling book on The Making of Biblical Womanhood, but it’s a question that’s stuck with me. I’m not rethinking my egalitarian views, but I have wondered recently if I’m wrong about a different topic: miraculous healing.

I often say that Luke and Acts are my favorite books of the New Testament because their astonishing accounts of healing make me think of my father. A retired physician who founded the neonatal intensive care unit of a major children’s hospital, Dad literally saved the lives of impossibly premature infants, and he explicitly did it in the name of Jesus.

But while I thought of him whenever I read Paul write about healing as a spiritual gift and knew how much my father depended on the power of prayer, I came to understand early that Dad worked miracles of human skill — inspired by human compassion and abetted by the technological results of human ingenuity — with tiny humans who exemplified humanity’s remarkable combination of fragility and resilience. I don’t think I ever thought of such healing as miraculous — in the sense that God was specially intervening in the world and setting aside natural laws.

Likewise, I’ve tended to think about the COVID vaccines in the way that Catholic theologian Brianne Jacobs described them, as a remarkable scientific achievement that “will bring us back to one another, allow us to breathe life back into the dust. That is a miracle.” By contrast, I’ve been frustrated to see so many Christians — including members of my extended family — scorn that kind of miracle and instead place their faith in “miracle cures” not backed by science.

I have zero doubts about my decision to get vaccinated. But in my skepticism about miraculous healing, I do seem to exemplify a phenomenon described by New Testament scholar Craig Keener: I’m just one more modern Christian who is culturally captive to an “antisupernaturalist” worldview that goes back to Enlightenment figures like David Hume. (A worldview that is not necessarily shared by Christians in the parts of the world where Christianity is growing fastest — see pp. 124-27 in Philip’s book, The Next Christendom.) Keener has a new book on miracles due out next week, a belated popular sequel to his 2011 academic treatise on miracles in the New Testament. In that first book, here’s how he summarized the problem:

When many Western intellectuals still claim that miracles or any events most readily explained by supernatural causation cannot happen, simply as as an unexamined premise, whereas hundreds of millions of people around the world claim to have witnessed just such events, some in indisputably dramatic ways, I believe that genuinely open-minded academicians should reexamine our presuppositions with an open mind.

Fair enough. As it happens, over the last two weeks, I’ve had two people of my acquaintance witness miraculous healing. So I’ve been trying to keep an open mind.

It started with someone I know very well. Earlier this year they told me that they had felt led to pray for the healing of a friend… a prayer that was immediately followed by dramatic, lasting improvement in their friend’s condition. Then not long ago, I heard more stories from the same acquaintance. Not all of their prayers led to healing, but several people reported drastically reduced pain.

I know this person well enough to know that they’re not naive, credulous, or hostile to modern medicine. They deride “faith healing” as manipulative and reject “health and wealth gospel” assumptions that healing is proof of faith. They’re angry at Christian anti-vaxxers and only pray if the person asking for that intercession has already sought out significant medical treatment.

But they are absolutely convinced that they possess the spiritual gift of healing and want to be obedient to what they see as God’s call on their life. “I believe you,” I told them. “I just don’t know what to do with it.” So I filed it away.

Then earlier this month, someone I follow on Twitter shared a thread telling a similar kind of story. Suffering from terrible pain and stiffness in his hand and wrist one Sunday morning, he took part in a session of Lectio Divina the next day and found himself meditating on Paul’s claim that “God raised Jesus from the dead. He will raise us up also” (2 Cor 4:14, NLV). A friend offered to pray for healing, and when he woke up the next morning, the “pain was like 99.9% gone, and my mobility was almost completely restored… Sometimes I hesitate to say things this boldly, but as far as I can tell, I was healed.”

These two people have very little in common. The first is a lifelong evangelical who attends a conservative Baptist church. The second is a worship leader who left my home denomination after coming out and describes himself (in the healing thread) as “an openly gay, liberal, agnostic Christian mystic.” Yet he is convinced that he “experienced a miracle, that somehow Jesus broke into my pain and my suffering and did an amazing thing, that somehow his resurrection power brought relief and healing to me.” And I’m sure the first person would say much the same thing about the healing miracles they’ve participated in.

I still don’t know what to do with these stories. I’m instinctively skeptical about them, but I don’t disbelieve such testimony. In fact, I want those accounts to be true. I want to be reminded of the power and love of a God who heals illness, eases suffering, and defeats death. Along with a pastor at the church where I taught this past weekend, I pray that God will work “inexplicable miracles that explode all the small boxes we put you in.”

In that sense, I think I want to be a medieval, not a modern.

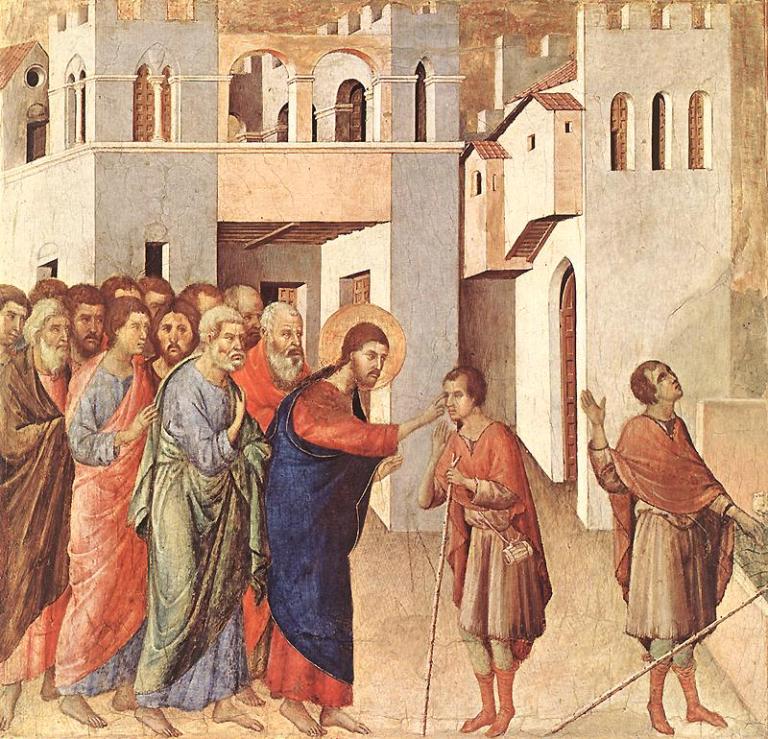

“Saints, visions, miracles, trial by ordeal, relics, and pilgrimage,” writes historian Chris Armstrong of the medieval world — “every square inch of the landscape was at least potentially inhabited by the spiritual.” And at a time of low life expectancy and high infant mortality, that landscape featured plenty of miracles of the healing variety. Bede’s history of the church in England, for example, tells of the dead being resuscitated and the blind coming to see. The pilgrims of Geoffrey Chaucer’s most famous work went to Canterbury, “the hooly blisful martir for to seke, / That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke,” with St. Thomas Becket’s just one of many healing shrines in medieval Christendom.

But two things strike me about how medievals understood such healing. First, medievalists like Jenni Kuuliala describe a harmonious relationship between medicine and the miraculous in that era. In a recent article, she writes that medievals had a “kind of synchronised attitude towards healing [that] has been called ‘medical pluralism,’ which includes the idea that there was no clear dichotomy between ‘orthodox’ and ‘unorthodox’ healing methods.” Either mode ultimately pointed back to God, since “[w]hatever curing method was used, whether it worked was dependent on God’s will.”

Second, living through a pandemic where we’ve sometimes seen Christians portray trust in medical science as reflecting a lack of faith in God, I’m particularly taken with Armstrong’s observation that the medieval concern for bodily healing was not primarily

of a mysterious or anti-scientific sort. Yes, occasionally healing might take miraculous form—through a prodigy of the sick person’s faith or the power of some saint’s relic. But most often healing meant simple nursing care, often at great risk to the caregiver’s own life. And it also meant the creation and development of the world’s greatest institution of mercy: the hospital.

According to Armstrong, medieval Christians “poured out huge amounts of their wealth and endangered their own health in order to attend to the physical health of others. Theirs was not a merely rhetorical compassion but a habit of compassion in action, underwritten by a coherent theology of physical healing.” (See also this issue of Christian History Magazine, edited by Armstrong.)

So I don’t know precisely where that leaves me with respect to my opening question. But medieval history helps me say this with confidence: whether through extraordinary instances of the utterly inexplicable or ordinary acts sustained by compassionate habit, healing is a miracle that, in Brianne Jacobs’ words, “manifests God’s power to restore life.”