Recent acts of violence and racism – most notably, the murders of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 and of eight Asian American women in Atlanta in March 2021 – have prompted intense discussions about how different groups experience the persistent problem of racism in the United States. Yet conspicuously absent in many conversations, especially those about Asian Americans, is a serious engagement in how religion shapes the ways that people both perpetuate and disrupt injustice.

Jonathan Tran aims to change how we understand racism and religion in America through his new book, Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism, published this month by Oxford University Press. Tran, who is Professor of Philosophical Theology and George W. Baines Chair of Religion at Baylor University, uses historical and ethnographic methods to understand how racial capitalism was enacted at two specific sites: a Chinese migrant settlement in the Mississippi Delta and the Redeemer Community Church in the Bayview/Hunters Point section of San Francisco.

The week it came out, the book was Amazon’s #1 new release in religious studies and #1 new release in political science at the same time. There’s clearly a lot of interest in the book, so I spoke with Tran to learn more about it.

Note: the interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Melissa Borja: Jonathan, tell me: why did you write this book?

Jonathan Tran: So the book has three big goals. The first goal is to try to understand race and racism, how they operate in America, and what’s going on where we are in this present moment. One of the things that’s driving the book is this question: If we universally agree that racism is bad, that it’s evil, that it causes untold destruction, then why does it persist? Why does it go on? Why is it still so prevalent? And the way I answer that question is I say racism persists because it works. It facilitates a system of extraordinary inequality, and it facilitates it by using race and racism as justification for that inequality. And so you can imagine a world in which you drive around your neighborhood or your city and you see certain people of color. You notice here that there’s dilapidated housing, there’s inadequate access to education, there’s limited resources for health care. And instead of asking the question, “What is wrong with our society that these folks don’t have access to these basic goods?” we instead blame the victims. We say it’s something about them, who they are, something about their race. I think in many cases that’s how racism works. It’s a system of domination and inequality that is justified by categories of and fictions around race. This is what’s happened and what’s been going on in this country since the beginning. Historically we know that race was used to secure labor and property distinctions, and it has consistently operated that way throughout American history and operates that way today.

Now this is a decidedly different picture of what racism is than what I would describe as the popular view. The popular view is a person is possessed of prejudices, or racist attitudes, often fueled by ignorance, a prejudicial culture, bad experiences, or what have you. The solution here would be simple enough: you go and correct that ignorance or get people to have better attitudes, maybe by exposure to so much diversity. In this popular view, racist attitudes sometimes rise to the level of structures and systems, but only sometimes. I think this view has it backwards. Racism operates as a set of structures and systems that then ingrain in individuals’ racist attitudes and behaviors, and this goes on as a cycle ad nauseum. We’ve tended to focus on the individual and the easy solution, when in reality we need to go after the structures and systems. To my mind, attempts to change racism and to pursue anti-racist agendas by changing hearts and minds without changing structures and systems are doomed to fail. Of course, we’re attracted to the all-too-convenient picture of the individual racist that sometimes rises to the level of structures and systems because it’s convenient to think that way. It allows most of us to go on with business as usual.

This popular, all-too-convenient view allows us to scapegoat the realities of our society and then put them on the heads of a hyperbolic image of racism—say, the Klansman or the red-faced sheriff armed with attack dogs. There are much larger structures and systems—for example, in relationship to housing. Redlining is certainly part of it, but it’s also the reality that rental gaps in communities, poor investment and infrastructures, poor governance and lack of access to democratic power, huge disparities in pay, huge disparities and access to education [play a part]. When we focus on the individual racist, we scapegoat those realities, oftentimes deservedly. Yet then we take our eyes off the structures and systems. We blame and scapegoat the individual racists, while many of benefit from the system, and insofar as we benefit from it, we perpetuate it.

MB: Okay, that’s just the first of your book’s goals. What’s the book’s second goal?

JT: The second thing I try to do is imagine Asian Americans as the miner’s canary of contemporary anti-racism conversations. And I do so by asking this question: Why is it that Asian Americans are not simply marginalized by anti-racist conversations, but consistently so? What I argue is that the way anti-racism is imagined in this country will inevitably lead to the marginalization of people already marginalized by racism. That’s why the events of last spring [in the wake of the Atlanta murders] were so illuminating, and revealing for, and of, so many Americans. They could not believe that Asian Americans experienced racism. So I asked the question: What is it about the way race operates, the way anti-racism operates, that Asian Americans are perpetually left out of the conversation? And then I look at the ways the conversation works.

MB: And the third goal?

JT: So the third thing I try to do is try to tell the story of Christianity and specifically the Christian Church, where there are still possible good outcomes for it. We all know, or we should all know, that in this country there has been a kind of unholy trinity between white people, Christianity and racism. What I try to do is disaggregate the Christianity and say that while a lot of Christianity is complicit in white racism, that’s not the whole story of Christianity. I try to imagine a story where God has not abandoned the church to its racism, even though much of the church deserves to be abandoned for its racism. So I try to tell the story of liberation as the activity of God and the way God invites Christians into this story, even if they perpetually and persistently reject that invitation.

MB: There are big visions for this book! I’m curious how you did this book. As I understand it, you are an interdisciplinary scholar, and you used ethnography along with theology and theory. Tell us about how you did the research for this book and how you pursued those three big goals.

JT: The questions I asked were raised through a theoretical apparatus often called “racial capitalism”—hence the title of the book—which is derived from the Black radical tradition. The way I talk about racism as always systemic and structural goes back to about one hundred years of reflection by Black radical theorists. So, this is nothing original to me. I’m simply drawing on a tradition of thought that’s been deeply respected and deeply helpful for us understanding things. I just apply it to the contemporary situation and describe it specifically in the history of Asian Americans. So that’s theoretically what’s going on.

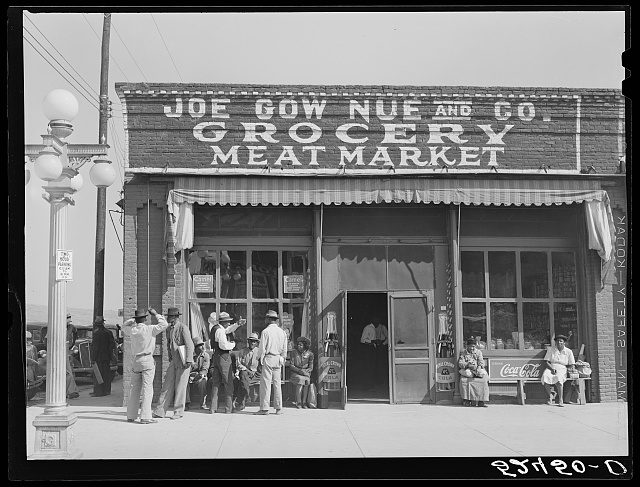

The book is divided into two big haves. The first part tells the history of Chinese migrants at the end of the 19th century, just after Reconstruction, who come to America as cheap labor. Shortly after, they remain in what is often referred to as “the most Southern place on Earth,” the Delta Mississippi. And they stay there and build stores in neighborhoods largely at the intersection between Black neighborhoods and white neighborhoods. They’re not allowed to live in white neighborhoods, and neither are they at home in Black neighborhoods, so they build stores and homes in between. On the one hand, the grocery store business leads to extraordinary forms of neighborly relationships. On the other hand, the stores are modes of exploitation insofar as the grocers take advantage of food deserts created by inequality.

My sense is that this picture of the way racism operates is a pretty common, if also banal, account of how racism most often operates in our society. It’s not driven by the racist with hyperbolic racist attitudes. It’s rather a system where we take advantage of inequality that comes downstream from systems of racism, racial domination, and that’s what these folks were involved in. Incidentally, because they live in the South, over time they become Southern Baptist Christians. And at one point, they become per capita both the most Christian and wealthiest Chinese Americans in the country. And so it’s an amazing history. Again, the dual reality of trying to be neighbors [and] exploiting inequalities. This, I think, is a picture of what racial capitalism is, what I describe in the book as a “moving picture of racial capitalism.”

The second half of the book is an ethnographic study of a contemporary church in San Francisco, the Bay View-Hunters Point part of San Francisco. It is one of the most marginalized parts of the city and home to what it’s often called Black San Francisco, the site of rather extraordinary and breathtaking forms of environmental racism. I tell the story of a group of Christians, the majority of whom, but not all of whom, are Asian-Americans, who eventually find themselves in Black San Francisco at the invitation and behest of Black churches in the area. What they do is begin to love their neighbors, and this means living with neighbors and finding out what the needs are of this community are. Because many of the people in this church graduated from nearby Berkeley or Stanford with computer science or electrical engineering degrees, they start a software company, and they use the software company’s income to redistribute money through the local neighborhood. It’s a picture of what I describe as an instance of the divine economy of God’s grace, in contrast to the racial capitalism I describe earlier in the book. The other thing they do is they use some of that money to start a school and give high-quality education to neighborhood kids for, you know, extremely affordable prices, basically for free. And so I try to offer this as one way of addressing the institutional structural, systemic realities of inequality and larger San Francisco.

MB: What lessons do you think we should take away from the stories at the center of your work? And more broadly, how do you think your book is going to change our conversation—how we think about racism, how we think about racial capitalism, how we think about what it means to be a good neighbor, and how we think about Asian Americans? What are your main interventions through this book?

JT: One of the most significant is at this current moment, we tend to think of anti-racism and racism in terms of questions of racial identity. We tell stories that are populated by specific racial personalities, and we suggest that the moral of the story has something to do with race as an essential quality of persons. I’m trying to shift the conversation to this larger one about the political economy—namely, racial capitalism—that creates these racial identities.

There are signs that our larger conversation is already beginning to make this shift. For example, the New York Times ran an opinion piece just the other day about what structural racism is, and what the op-ed pointed to are thinkers that I also draw on in my book, like Oliver Cromwell Cox, and what Cox called a “world systems” analysis. These systems are often tied to not simply the local, but the state, the national, the global. That’s one thing that’s very powerful conceptually about introducing Asian Americans into this story. As you and your own work have shown, the transnational global reality of, say, Asian migration shows the global transnational—and, in our case, Trans-Pacific—systems of oppression, domination.

The other part of the intervention I hope to make is that in recent years, Christian academics have certainly told the story of how racist Christianity can be. It can be terrifyingly racist, and we can and should continue to tell that story. But we also need stories that tell different stories about what Christians can do insofar as they can do those things, insofar as they are Christian.

In doing so, one of the things I try to emphasize is that the primary key of Christian life is not resistance, but proclamation. What I try to say is that liberation is natural to the world because it’s natural to God. Justice and mercy are natural to the world because they’re natural to God. Those are features God builds into creation insofar as God created the world. So I argue that rather than Christians having to make something happen, start a revolution, really what they need to do is lean into a revolution that is 2000 years in the making.

MB: What you’re talking about is so provocative, and I appreciate your attention to not only stories of failing to live out values and commitments, but stories that can offer models for how to live a life that is more virtuous and in keeping with Christian commitments. That is very generative.

There are so many connections between your work and the work of other scholars, some of whom wrote a century ago and some of whom are writing right now. I know that there is a really lively conversation about Asian Americans today. I’m thinking, for example, of Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong and also Jay Caspian King’s book The Loneliest Americans. I wonder how you see your book connecting to this current conversation led by Asian American people talking about Asian American experiences in the 21st century.

JT: I begin the book with a quote by Angela Davis and then a quote by Cathy Park Hong and then a quote by Jay Caspian Kang. So yeah (laughing), they have been hugely influential to me. I consider Kang to be one of our most astute cultural observers, specifically around issues of race and racism. I imagine Kang and I are in agreement that, as he says, Asian American identity is mostly meaningless. What he means by that it’s hard to point to some concrete reality, right? There’s not an Asian American language, most of us don’t go back to Asian America when we go visit our families. So it’s not quite clear what the term means.

We know it’s incredibly difficult to capture the amazingly diverse histories of Asian Americans, right? You have not only different countries, but different cultures, different religions, different languages, different ethnicities, different histories. My family’s migration to America as war refugees at the end of the Vietnam War is a very different thing than, say, folks coming from Taiwan to go to Cornell to get graduate degrees in electrical engineering. Those are very different histories to capture all of that under, say, “Asian American” as a category. It’s unclear what Asian American identity means, and so I try to trouble the easy commitments to racial identity for Asian Americans. That’s where I agree with Kang.

I think the inverse also applies for me and Kang. That is, we want to really think through how we’re imagining racial identity in anti-racism, and we each want to avoid reinforcing the racial categories, especially when it comes to white people as if their being white is the only thing about them that matters. Offering holistic judgments on white people like “whiteness” or “white fragility” may capture some things, but the worry is that in doing so, we reinforce white racial identity when what we want to do is destabilize white racial identity.

What makes my book different from Minor Feelings and The Loneliest Americans is that it is a theology book written by a confessional Christian. What that means is that my work tries to be in service to some determinative end that has to be concretely and materially realizable or realized. It has to show up in the world with and as a group of people, and to me, that group of people is the church. So I take what might be theoretical or abstract ideas and locate them very specifically in groups of people who live faithfully or don’t live faithfully in terms of what I think the Gospel requires and makes available to us.