In the opening years of the eighteenth century, England experienced an outbreak of spiritual excitement, and indeed excess, of a kind that many societies have noted before and since. People claimed amazing spiritual and mystical episodes, accompanied by stories of prophecies, healings, and even resurrections. Sometimes, such phenomena betoken a religious revival, or might at the disreputable fringes of such a revival. On this occasion, though, the extreme manifestations – what people at the time called “enthusiasm” or fanaticism – were very much the centerpiece of the story. This particular wave of religious excitement differed from its predecessors in that some learned people tried to analyze it as a social and psychological phenomenon, and in so doing, they created a whole new vocabulary.

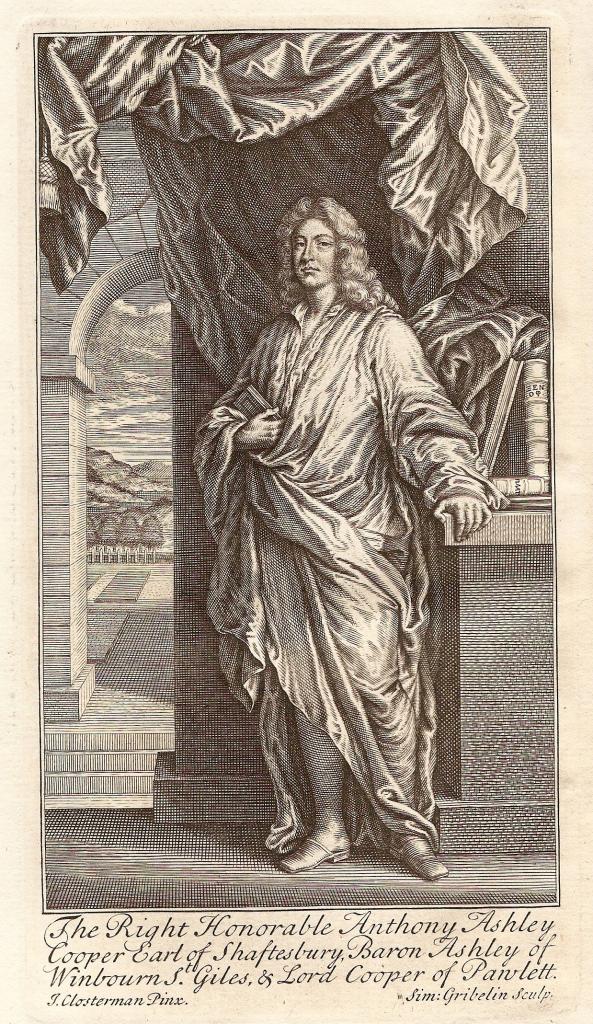

Last time, I talked about the sensational arrival of the French Prophets in London in 1706, and the general wave of excitement that followed over the next two years. That created massive blowback, and not just from outright skeptics. One powerful response to the affair came from a famous philosopher of the day, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the brilliant third Earl of Shaftesbury, who was what we might today call a leading public intellectual.

In late 1707, as the Prophets affair was at its height, Shaftesbury wrote a letter to an anonymous “Lord,” presumably Lord Somers, and this was published the following year as A Letter Concerning Enthusiasm. Although he did not attack the idea of a state church, Shaftesbury believed passionately in generous religious toleration and condemned religious coercion or persecution. The Letter Concerning Enthusiasm was widely quoted in subsequent debates, and had a profound impact on Enlightenment approaches to faith and toleration.

The Letter featured a sophisticated analysis and denunciation of extremism or fanaticism, above all in matters of religion. Earlier writers had commented on wild upsurges of bizarre sects, for instance in England in the 1640s, but they had usually denounced them for their spiritual or demonic quality. Shaftesbury’s approach is entirely secular, because as he argues, religious extremism had dire real-world consequences. We can still find value in his account of how such wild enthusiasm spreads, especially in terms of social crisis, when it is analogous to a fever infecting the body politic, driving “Bloodshed, Wars, Persecutions and Devastations.” Following the medical ideas of the time, he discussed infection in terms of vapors, and the theory of the humors, hence “melancholic.”

To describe such fevered moments of groundless terror, Shaftesbury coined a new word, which he drew from the Classical story of the wild fear that the god Pan used to scatter his enemies:

We read in history that Pan, when he accompanied Bacchus in an expedition to the Indies , found means to strike terror through a host of enemies , by the help of a small company whose clamors he managed to good advantage among the echoing rocks and caverns of a woody vale. The hoarse bellowing of the caves, joined to the hideous aspect of such dark and desert places, raised such a horror in the enemy that in this state their imagination helped them to hear voices, and no doubt to see forms too, that were more than human: whilst the uncertainty of what they feared made their fear yet greater, and spread it faster by implicit looks than any narration could convey it. And this was what in after times men called a Pannick [panic] . The story indeed gives a good hint of this passion, which can hardly be without some mixture of enthusiasm, and horrors of a superstitious kind. (23-24)

The Earl was apparently the first writer in English to use the word “panic” as a noun, rather than an adjective. Previous authors had talked about panic (Pan-ic) fear, but he now invented “a panic,” and he did so in a clearly religious context:

We may with good reason call every passion Pannick which is rais’d in a multitude, and convey’d by aspect, or as it were by contact or sympathy. Thus popular fury may be call’d pannick, when the rage of the people, as we have sometimes known, has put them beyond themselves; especially where religion has to do. And in this state their very looks are infectious. The fury flies from face to face: and the disease is no sooner seen than caught. Those who in a better sensation of mind have seen a multitude under the power of this passion have own’d that they saw in the countenances of men something more ghastly and terrible than at other times is express’d on the most passionate occasions ….

Thus my Lord there are many Pannicks in mankind, besides merely those of fear. And thus is Religion also Pannick; when enthusiasm of any kind gets up; as of, on melancholic occasions, it will do. For vapors naturally rise, and in bad times especially, then the spirits of men are low, as either in public calamities, or during the unwholesomeness of air or diet, or when convulsions happen in nature, storms, earthquakes, or other amazing prodigies: at this season the Pannick must needs run high, and the magistrate of necessity give way to it (pp.25-26).

“Thus is Religion also Pannick; when enthusiasm of any kind gets up.” That vision would readily spring to the minds of the enemies and critics of revivalism, in 1740, in 1798, in 1906, and on so many other occasions. One person’s glorious revival is another’s religious panic. Might critics have spoken of a great spiritual panic attack?

It is notable that Shaftesbury singles out climate factors as a driving force at moments of “panic.” By 1757, the very modern notion of a financial panic was also well established.

Beyond the “panic” theme, Shaftesbury offered a plausible basis for discussing religious excess. If we do not accept them at face value, how are we to account for enthusiastic experiences, when people fall prey to the craziness of groups like the French Prophets? As he said, such experiences are “those Delusions which come arm’d with the specious Pretext of moral Certainty, and Matter of Fact.” Crucially, he noted how very hard it was to tell genuine spiritual experience from bogus:

Enthusiasm is wonderfully powerful and extensive … [and] … it is a matter of nice Judgment, and the hardest thing in the world to know fully and distinctly… Nor can Divine Inspiration, by its outward Marks, be easily distinguish’d from it. For Inspiration is a real feeling of the Divine Presence, and Enthusiasm a false one. But the Passion they raise is much alike.

As a modern commentator notes, “Scary noises in a dark cave can produce the same feeling of fear, whether they are caused by many monsters or one trickster. The feeling itself does not constitute proof that the feeler’s belief about the cause is correct.” Fortunately, we today are thoroughly expert in distinguishing between authentic religious experiences and outright delusions … oh wait, no we’re not, not even slightly.

Written in 1708, Shaftesbury’s Letter still amply repays our attention.

Although the vocabulary differs somewhat, the picture of “panics” presented by Shaftesbury is very much the same as that in Charles Mackay’s classic 1841 study of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. For an updated version of Mackay’s work, see William J. Bernstein, The Delusions of Crowds: Why People Go Mad in Groups (2021). There are also analogies to the sociological concept of the “moral panic” formulated in Britain in the 1970s, and a theme on which I have published quite a bit. In terms of the specific application to religious “panics,” I particularly think of the epic study by Brazilian author Euclides da Cunha, Backlands, about a real-life messianic / millenarian movement in the 1890s, on which I posted here some years ago.