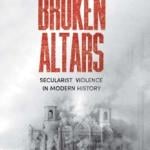

While religious Americans might have exaggerated the “godlessness” of communism during the Cold War, they were spot-on with respect to one state: Albania. The communist regime that swept to power there after World War II dealt with clerical opposition by killing or imprisoning vocal clerics, whether Catholic, Orthodox, or Muslim—although the more educated Catholic clergy had it particularly bad with the entire hierarchy (save one bishop) being wiped out by the 1950s.

I have recently returned from the small country (just a hundred miles from Italy across the Ionian Sea) doing fieldwork for a new scholarly project, tentatively entitled Unholy Wars: Secularist Violence in Modern History.

I will have more to say about the postwar situation in Albania (and other Eastern European states) at a later point, but permit me to spotlight here the year 1967, when the communist party leader and dictator Enver Hoxha (r. 1944-1985), a committed Marxist-Leninist but also an ardent Albanian nationalist, and his enablers made any form of religion illegal, crowing to the world about having created “the first atheist state in the world.”

Throughout the 1960s the situation in Albania had worsened as Hoxha, breaking with Nikita Khrushchev and beholden Mao Zedong after the Sino-Soviet Split of 1961, felt Albania, copying China, should undergo its own “Cultural and Ideological Revolution.” Hoxha announced its anti-religious dimension on 6 February 1967, inciting young people to cast off “superstition” and traditional habits of being. An open letter on 27 February argued that “we must direct our struggle against religion as much as against religious dogma . . . [and] against religious practices that have penetrated the daily existence of believers.” On 22 November, a new decree (#4337) repealed previous laws that paid lip service to freedom of conscience, essentially criminalizing religious belief.

These measures coincided with a state-orchestrated campaign against sacred architecture. Astoundingly, every church, chapel, mosque, monastery, and Sufi shrine (tekke) in the country was either destroyed or re-purposed for non-religious purposes, such as a gym, granary, cinema, or warehouse. Orthodox icons, wrenched from churches, were used as firewood. Spectacular footage exists (viewable now on YouTube) of whole churches being dynamited and of Red Guards of the Albanian Youth hacking at their religious heritage with pickaxes. A remarkable photograph displayed at the Site of Witness and Memory (a museum on religious persecution in the city of Shkodër that I visited) shows a female gymnast swinging on flying rings in the city’s cathedral above where the altar once stood. Partisans set fire to the Franciscan cloister in Shkodër, killing four elderly friars. In all, the late 1960s witnessed the destruction, vandalizing, or re-purposing of 2,169 sacred sites. Some structures believed to have extraordinary cultural significance were spared as “national monuments.” Not uncommonly, re-purposed buildings underwent modifications to blunt their original religious intent lest they have “negative psychological influence on the younger generation,” as one government memorandum put it.

Amid the destruction, Muslim and Christian clergy were denounced as social parasites. Those who resisted, numbering in the hundreds, found themselves in prison or labor camps such as Spaç,which I visited, in remote northern Albania. Others had to attend “re-education” classes and were given menial jobs such as cleaning toilets or sweeping the streets.

The frenzy against religion in the 1960s (technically extralegal) preceded constitutional changes in the 1970s. Article 37 of the revised Constitution of 1976 makes clear that “the state does not recognize any religion at all, and supports and develops atheistic propaganda in order to implant in mankind the scientific-materialistic world-view,” while Article 55 forbids “the creation of any type of organization of a fascist, anti-democratic, religious, or anti-socialist character.” The revised Penal Code of 1977 set three- to five-year prison sentences for producing, storing, or distributing religious materials.

Additional decrees took issues with names. Parents were forbidden to choose biblical or Qur’anic names for their children and enjoined to change their own names if derived from these sources, choosing instead from 3,000 suitably secular and “national” names listed in the Dictionary of People’s Names.

Not least, holidays such as Christmas or Easter or the Muslim Eid al-Adha wound up on the chopping block. Officials cunningly tried to entrap practicing Christians and Muslims during religious fasts, such as Lent and Ramadan, by distributing forbidden foods in school and work, and then publicly denouncing those who refused to eat. Days celebrating national independence, “the glory of work,” and even the country’s acquisition of electricity were offered as ersatz “holy days” . . .

Again, I will have more to say at a later point. But “godlessness” is perhaps not far from the mark.