I’ve been long in the habit of sharing enjoyable reads from the last year. For the past few years I’ve done this on social media. This is the first time, in a bit, that I’ve put together an article about my reading from the past year, so it’s worthwhile to share my reading habits, interests, and goals. Since I’m a historian, my reading predominantly favors this discipline, and the list I craft each year is on history books. That’s not the extent of my reading interests, which I’ll discuss below.

Reading Habits

Since I was a child, reading has been my preferred leisure habit or hobby. I read daily. I engage in reading early in the morning, during meal breaks, and any passive moments I have. I have a surprising amount of passive time; I shuffle kiddos around from school to events; I run errands for my family; I grocery shop; I commute to and from work; and I do house projects. I count consuming audio books as “reading,” and my preferred consumption while I engage in these activities is audio books.

You’d be surprised how much audio reading you’re able to do while doing house projects. This past year I repainted our master-bedroom, family room, kitchen, and my son’s room. During that time, I listened to Bernard Bailyn’s Barbarous Years and much of Gordon Wood’s Empire of Liberty.

That said, I also have regular rhythms of the week where I set aside a large chunk of my day to read or re-read a good old fashioned print book or Kindle e-book on my phone. Books I read in print are commonly crucial texts in my field of research and teaching, ones that are necessary for future research, or are current re-assessments of the state of the field in areas of my interest. Re-visiting the history of evangelicalism, empire, and race has been of interest to me this past year. Examples of this kind of reading include Carla Pestana’s Protestant Empire, Thomas Kidd’s Protestant Interest, and Albert Raboteau’s Slave Religion.

I mentioned re-reading above and this is an important notion. Immersive and deep reading requires re-reading. Sometimes I re-read an audio book in the print medium, or, vice versa, I’ll listen to a book I’ve read in print to reinforce my memory with the audio medium. In fact, there are books that I have listened to, read on Kindle, and then re-read in print. I’ve done this with books that I’ve selected as critical for my learning and research. Examples of books I’ve done this with include Henry Louis Gate’s Black Church and Alan Taylor’s American Colonies.

I get quite a bit of print and digital reading done during the evenings and weekends. I occasionally get lost in an Oxford, A Very Short Introduction during a weekend and binge it like candy or popcorn. I read Michael Freeden’s Liberalism, John Guy’s The Tudors, and John Morrill’s Stuart Britain in that fashion this year. I always have a Kindle e-book on hand, so any time I have a passive 10–15 minutes I can put it to that kind of reading; or, if I’m having trouble sleeping, I can read a Kindle e-book until I drift off to sleep. This last year, I frequently drifted off to sleep reading sources on witch-hunts, such as, Erika Gasser’s Vexed with Devils or Elaine Breslaw’s Tituba: Reluctant Witch of Salem.

Reading Interests

While my best books lists are always secondary historical sources, that is not the extent of my reading. Every year I read a number of primary texts and pieces of literature. I love reading from both the Loeb Classics Library and the I Tatti Renaissance Library. This year I focused towards the topics of rhetoric and liberal arts and, with Nadia Williams’s recommendation, I accompanied my readings with George Kennedy’s Classical Rhetoric and Its Christian and Secular Tradition (UNC Press). Among this year’s readings included Aristotle’s Poetics, Basil’s letter “To Young Men,” Bruni’s letter to Lady Batista Malatesta “The Study of Literature,” and Piccolomini’s “The Education of Boys.”

I don’t just read classical works. As an early modern historian, it’s been essential to read classics and primary sources in my area of expertise. This past year I either read or re-read Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (Norton), John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, The Works of Phyllis Wheatley (Penguin), and David Walker’s Appeal (UNC press), Hawthorne’s Goodman Brown (Penguin), W E B Dubois’s The Souls of Black Folks (OUP), and H. P. Lovecraft’s The Witch’s House (Penguin).

Reading Goals

Reading goals and objectives are good. I know people who set daily page reading goals or goals on how many books they read in a year. I’ve set such goals in the past, but I haven’t done so in recent time, nor have I kept up with how many books I read.

Partly this is because I end up having to be an occasional reader. What that means is that circumstances sometimes dictate my reading. Issues in culture and society or surprising turns in my lectures or research will direct my reading into another direction. I read large chunks of Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (Simon & Shuster) this past month for this reason. I also make commitments that reshape my reading goals. For instance, I committed to have a book talk with James Ungureanu about his book, Science, Religion and the Protestant Tradition (University of Pittsburgh Press) at the end of this month, which repositioned his publication to the forefront of my priorities.

Recently, my reading goals have been to read towards diversity and read deeply upon topics I will write. Thus, I read towards race and gender studies, and I gravitate towards topics related to witch-hunts and evangelical history.

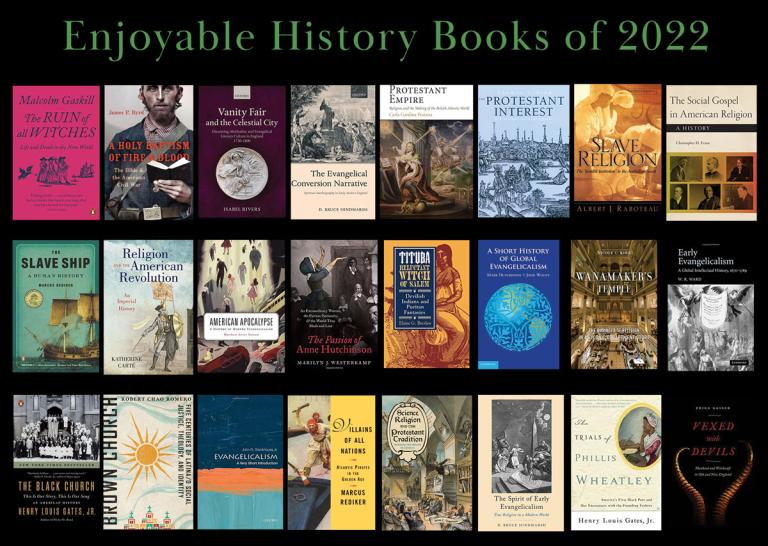

My 2022 Book Recommendations

I typically share at the end of the year 24 books I enjoyed over the past 12 months, so with no further ado, here are those picks.

Vexed with Devils (NYU Press, 2017) by Erika Gasser is an outstanding transatlantic study that discusses the role of masculinity, among the accused, in witch-hunts during the seventeenth century. Malcolm Gaskill’s The Ruin of All Witches (Knopf, 2022) is a delightful narrative history on Springfield Massachusetts, William Pynchon, and the story of the witch accusation of Hugh and Mary Parsons. Tituba: The Reluctant Witch of Salem (NYU Press, 1995) by Elaine Breslaw has challenged me to think about the role of race in witch-hunts and the pivotal role that Tituba played in shaping the narrative of the Salem Witch Hunt of 1692.

Maritime studies interest me because I hope to develop a maritime religious history course in the future. Marcus Rediker has given me deeper understanding of the transatlantic slave-trade with his now classic, Slave Ship (Penguin, 2007), and his Villains of All Nations (Beacon Press, 2005) has oriented me to the history and social condition of pirates.

Slave Religion (Oxford University Press, 2004) by the late Albert Raboteau and Henry Louis Gates’s The Black Church (Penguin, 2021) and The Trials of Phyllis Wheatley (Civitas, 2010) have been crucial works in my ongoing study of slave and black religion in U. S. history. The select case studies recorded in Robert Chao Romero’s Brown Church (IVP Academic, 2020) oriented me to the long history of religion among Latin Americans. I’m currently reading Christianity in Latin America by Ondina and Justo Gonzalez to deepen my understanding in this area of history. James Byrd’s A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood (Oxford University Press, 2021) provided a solid chronological account of the Civil War, while seamlessly integrating within it the history of the bible’s use in that conflict.

I keep returning to twentieth-century Protestant and evangelical studies. Christopher Evans’s The Social Gospel in American Religion (NYU Press, 2017) has been a vital overview for me. Nicole Kirk’s Wannamaker’s Temple (NYU Press, 2018) reinforced the connection between commerce and consumption to the growth of fundamentalism and evangelicalism, and Matthew Avery Sutton’s American Apocalypse (Belknap Press, 2017) confronted me with how much prejudice and racism shaped the culture of premillennial fundamentalism and the role biblical interpretation and theology played in reinforcing that culture.

Continued study in the long history of evangelicalism played a significant role all year. W. R. Ward’s Early Evangelicalism: Global Intellectual History, 1670–1789 (Cambridge University Press, 2006) provided a backdrop for the mystical inclinations within evangelical history. Bruce Hindmarsh’s study on The Evangelical Conversion Narrative (Oxford University Press, 2005) worked in tandem with the ideas from Isabel Rivers’s Vanity Fair and the Celestial City (Oxford University Press, 2018). Hindmarsh’s The Spirit of Early Evangelicalism (Oxford University Press, 2018) also brought into conversation developments in art, technology, and science and how evangelicals engaged in those enterprises, as they furthered the evangelical vision. Kidd’s The Protestant Interest (Yale University Press, 2004) and Pestana’s Protestant Empire (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010) coordinated together and conveyed how empire, particularly the British empire, colonized and spread Protestant belief, which cultivated the ground soil for evangelicalism to spring forth. John G. Stackhouse, Jr. has now provided for us Evangelicalism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2022), which will prove to be a reliable and quick overview of the subject, but it is no replacement for Mark Hutchinson’s and John Wolffe’s A Short History of Global Evangelicalism (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Among the occasional reads for this year included The Passion of Anne Hutchinson (Oxford University Press, 2021), which is Marilyn Westerkamp’s excellent recount of the Hutchinsonian controversy in the 1630s of Massachusetts Bay Colony. Look for my review of it in a forthcoming issue of Fides et Historia. Katherine Carté’s Religion and the American Revolution (UNC Press, 2021) provided sound scaffolding and pillars to re-examine the transatlantic role of Awakener’s in the conflict between Britain and her colonies across the Atlantic. You can listen to my conversation with Carté about her book on the CFH podcast. Finally, James Ungureanu’s Science, Religion and the Protestant Tradition (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019) is a revision history on the conflict thesis between science and religion and a valued contribution to this field of history. You’re invited to join James and I as we talk about his book during the next CFH Book Talk today at 12PM CT.