Today we have the pleasure of welcoming a guest contribution from Jacob Huneycutt, a history M. A. student at Baylor University. You may follow @jacobhuneycutt_ on Twitter.

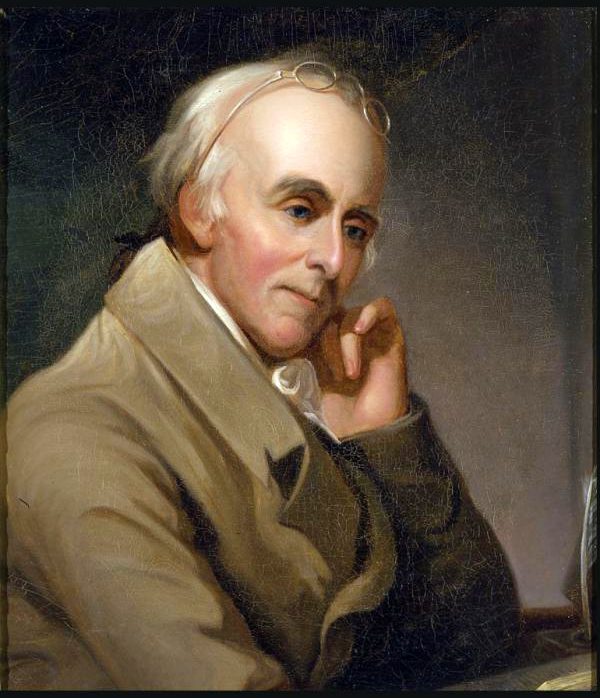

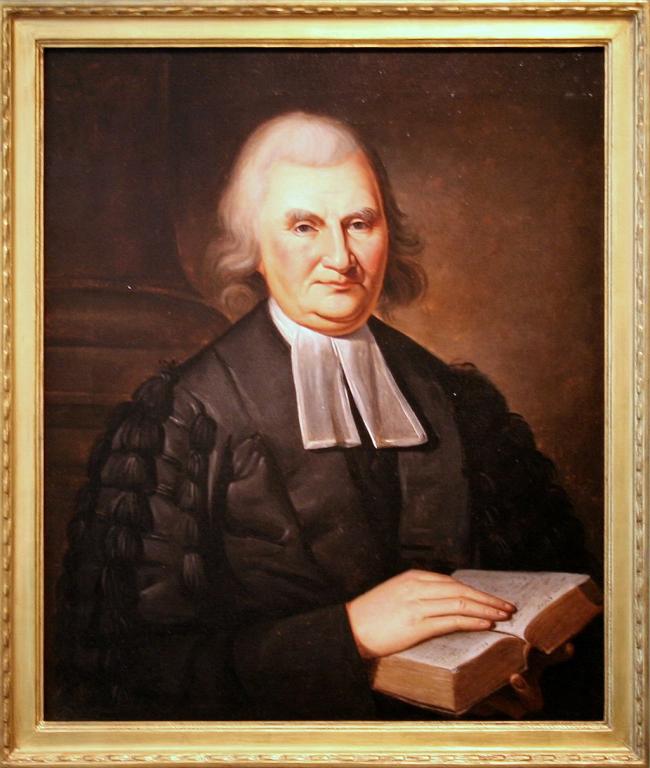

“If the measure for memorializing men and women from the past is perfection, we won’t be left with many heroes.” In an essay written last week for Princetonians for Free Speech, Kevin DeYoung offered that advice on why we should continue to honor John Witherspoon (1723-1794), one of America’s Founding Fathers and the sixth president of Princeton University, as a hero and why the statute of him at Princeton should not be torn down. Witherspoon, a Scottish-born Presbyterian minister, is known for having been the only active clergyman to have signed the Declaration of Independence. As a confessionally Reformed minister, he is often held up as an example of how the Founding Fathers were not all deists. And his leadership helped cement Princeton as a hub of old-school Reformed theology for more than a century. However, he was also a slaveowner, purchasing at least two slaves during his lifetime.

“If the measure for memorializing men and women from the past is perfection, we won’t be left with many heroes.” In an essay written last week for Princetonians for Free Speech, Kevin DeYoung offered that advice on why we should continue to honor John Witherspoon (1723-1794), one of America’s Founding Fathers and the sixth president of Princeton University, as a hero and why the statute of him at Princeton should not be torn down. Witherspoon, a Scottish-born Presbyterian minister, is known for having been the only active clergyman to have signed the Declaration of Independence. As a confessionally Reformed minister, he is often held up as an example of how the Founding Fathers were not all deists. And his leadership helped cement Princeton as a hub of old-school Reformed theology for more than a century. However, he was also a slaveowner, purchasing at least two slaves during his lifetime.

In his 3,500-word essay, DeYoung paints Witherspoon in nearly the best possible light, considering his slave-owning. He argues that since Witherspoon supported the gradual abolition of slavery, baptized a runaway enslaved man named James Montgomery, and taught free black men, his slave-owning should be understood as just a blind spot—not unlike the blind spots we all have today. DeYoung proposes that if we would not want our life work to be judged based on our blind spots that will seem clearer to people in the future, then, it is not fair to judge the life work of a man who was “actually fairly enlightened for his age” based on his.

However, history complicates the idea that John Witherspoon’s choice to own two enslaved persons can be explained away as just a blind spot. First, John Witherspoon was geographically and relationally adjacent to anti-slavery advocates. One example is Benjamin Rush, one of the two men who invited Witherspoon to move to America and take the job as the president of Princeton University, and a friend of his who eulogized him following his death. [1] Yet Rush wrote a pamphlet in 1773 in which he condemned slave-owning in the strongest terms possible. He wrote:

Think of the many thousands who perish by sickness, melancholy, and suicide, in their voyages to America. Pursue the poor devoted victims to one of the West India islands, and see them exposed there to public sale. Hear their cries, and see their looks of tenderness at each other, upon being seperated.—Mothers are torn from their Daughters, and Brothers from Brothers, without the liberty of a parting embrace. Their master’s name is now marked upon their breasts with a red hot iron. But let us pursue them into a Sugar Field: and behold a scene still more affecting than this—See! the poor wretches with what reluctance they take their instruments of labor into their hands,—Some of them, overcome with heat and sickness, seek to refresh themselves by a little rest.—But, behold an Overseer approaches them—In vain they sue for pity.

This is instructive, as it shows that educated, elite, white men living in the British American colonies in 1773 were either fully aware, or easily could have made themselves aware, of how reprehensible slavery was.

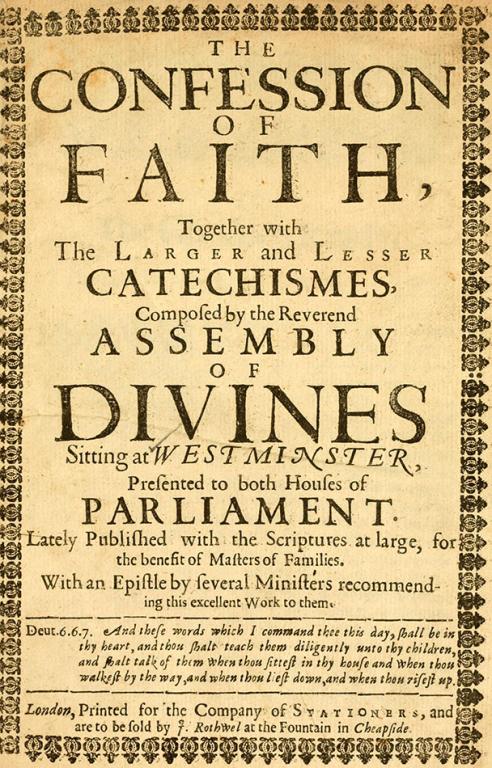

Additionally, the witness of a group of Presbyterians known as the Covenanters, who largely lived near Witherspoon in Pennsylvania, demonstrates that one could hold to conservative Reformed theology in the eighteenth century and yet be a committed abolitionist.[2] While the Covenanters are known for their extreme fidelity to seventeenth-century Reformed doctrine, as articulated in the 1646 Westminster Standards, and their refusal to support the United States Constitution due to its failure to acknowledge Christ as the source of the government’s authority, it is less known that they opposed slavery from their very origins.[3] Samuel Rutherford (1600-1661), an early influential Covenanter theologian, wrote that “slavery … is not natural, but against nature.”[4] This is one of the reasons why they refused to support the U.S. Constitution. One Covenanter pastor, Samuel Wylie, argued that since “the practice of slaveholding [was] flatly repugnant” to Scripture, the Constitution stood in contrast to God’s moral law.[5]

Considering all of this, at what point do we acknowledge that Witherspoon easily could have, and should have, known better than to buy and own slaves? Instead of arguing that he was “a man of his time,” at what point do we acknowledge that while others in the same area, and others who were philosophically and religiously similar to him, opposed slave-owning, he decided, instead, to be a moral coward on the issue? Yes, Witherspoon’s actions were very human, and the gospel of Jesus Christ can even save slave-owners. But given what he could have, and should have, known, should he be reckoned as a hero?

Those of us who are confessional, Reformed Christians today should instead look to the moral courage that the Covenanters displayed on the issue of slavery. In the eighteenth century, they took fidelity to God’s moral law so seriously that, partly because the United States government supported the institution of slavery, they refused to assent to the Constitution. The least that we could do today is to take sin seriously enough that we refrain from writing articles in defense of the heroism of slave-owning men from our founding generation. History shows that they could have, and should have, known better.

Exodus 21:16 (KJV) — And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.

1 Timothy 1:9-10 (KJV) — Knowing this, that the law is not made for a righteous man, but for the lawless and disobedient, for the ungodly and for sinners, for unholy and profane, for murderers of fathers and murderers of mothers, for manslayers, for whoremongers, for them that defile themselves with mankind, for menstealers, for liars, for perjured persons, and if there be any other thing that is contrary to sound doctrine.

[1] Jeffry H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 2.

[2] Joseph S. Moore, “Founding Sins: How a Group of Antislavery Radicals Fought to Put Christ into the Constitution,” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 38.

[3] Joseph S. Moore, “Covenanters and Antislavery in the Atlantic World,” Slavery and Abolition, vol. 34, no. 4 (2013), 545, 554.

[4] Moore, “Covenanters and Antislavery,” 541.

[5] Moore, “Covenanters and Antislavery,” 544.