Can a whole society have a life verse?

As I argue in my recent book, Psalm 91 is one of the scriptures most used by Christians and Jews through history to confront a variety of dangers, most tellingly war and disease. The psalm, after all, appears to promise that those who invoke not only may be protected from harm, but that they assuredly will. We find examples of such invocations throughout the past couple of millennia, but I was struck just how very commonplace they were in a period dear to my heart, namely the nineteenth century US. At the time, it was assuredly the most commonly used psalm, far more so than the 23rd. It became the life verse of a society – well, more accurately perhaps, its death verse.

The War Psalm

The obvious occasion for such uses was the Civil War, when 91 was so often invoked for protection.Who could fail to turn to a psalm that promised the believer that “A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee”?

There are so many possible examples to choose from that I can only graze here. When the survivors of the Union’s Taylor’s Battery gathered for a reunion in 1880, they recalled the opening days of the war in a scene that must have occurred (at least) hundreds of times across the nation in those weeks, North and South:

A kind Providence certainly watched over this battery from that Sabbath day, May 28, 1861, when in a body we attended the First Presbyterian Church [Chicago], and when the pastor, Dr Humphrey, called our attention to Psalm XCI [ie, 91, which is then quoted in full]… Then devoutly and with much earnestness he besought God in prayer to be gracious to us, and to protect us while in camp, on the march and in the field. Who of us today will not say that the prayers of that pastor and his church were wonderfully answered and that God was “our refuge and our fortress?…. Nothing but the Divine protection saved us again and again from being captured or entirely crushed.

On the other side of the conflict, here is the nineteen year old Confederate soldier Randolph Harrison McKim, writing in July 1861, and freely quoting 91:

Do not, my precious mother, be too much alarmed and too anxious about me. I trust and hope that God will protect me from “the terror by night” and “the destruction that wasteth at noon-day.” I feel as if my life was to be spared. I hope yet to preach the Gospel of the Jesus Christ; but, my dear mother, we are in God’s hands, and He doth not willingly afflict or grieve the children of men. “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty.” He does all things well, and He will give you grace to bear this trial too.

When Confederate Cadets marched off to war in Petersburg, VA, in September 1861, the Rev. Robert Newton Sledd preached a sermon assuring them that:

And surely if any one has need of the constant protecting care and power of an almighty hand, that one is the soldier. …. And although he may escape the missiles of the foe, the air which he breathes is loaded with disease; and often when he thinks himself the most secure, the enemy is fixing its deadly fangs in his vitals. Oh, then, humbly submit yourselves to God! Seek shelter “in the secret place of the Most High,” that you may find protection from “the arrow that flieth by day,” and “the pestilence that walketh in darkness.” Let the God of Jacob be your God, His will your will, and his glory your end. Then may you claim that promise which saith, “A thousand shall fall at thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee. Only with thine eyes shalt thou behold and see the reward of the wicked.”

Also in 1861, a Mississippi cavalry commander submitted an official report of his unit’s actions in the day’s battle: “And first allow me to record with gratitude the kind Providence which shielded us in the day of battle and saved so many from ‘the destruction that wasteth at noonday.’ ” Another of the many soldiers to leave his recollections was the Union’s John Beatty, later a prominent figure in Ohio politics. In January 1863, he noted how his unit’s morale was rising: “I draw closer to the camp-fire, and, pushing the brands together, take out my little Bible, and as I open it my eyes fall on the XCI [91st] Psalm,” which he then quotes in full.

The psalm features regularly in accounts of heroic and dying soldiers—not by any means as the only scripture so employed, but as a deeply valued text. When Stonewall Jackson was killed in 1863, it was only natural to commemorate the great Godly warrior through that Psalm. One sermon, preached in Lynchburg’s First Presbyterian Church, took its text from the Psalm, “I will set him on high, because he hath known my name”:

Our text which is but a statement of this truth, is a concentration of Gen. JACKSON’S whole history. It is his life and his character, his fame and its secret source, all in a single sentence. It declares the secret of his great eminence. God set him on high, because he honored God. This whole Psalm beautifully and strikingly applies to him. It describes the Divine protection and honor of the man that dwelleth in the secret place of the Most High, that says of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress : my God, in him will I trust. It is of him that God here says, “I will set him on high, because he hath known my name.”

Warding Off Evil

The Psalm was meant to be apotropaic, that is, to ward off evils. Here is the Union’s Major Henry Meyer in 1862, after the battle of Cedar Mountain:

I then took out my pocket Testament and went to a picket fire near where I was, leaning over to read a verse or two by its light, when I heard a rustle in the bushes. Immediately I grasped my weapons and was on the alert, when a colored man crawled through the bushes and said to me, “What’s that you got there, a Testament?” On admitting it, he said, “Do you know the chapter General Washington always used to read before he went into a fight?” I told him I did not, whereupon he said, “You turn to the Ninety-first Psalm.” “Now,” he said, “you read it.” I then read aloud:

“Surely He shall deliver thee from the snare of the fowler and from the noisome pestilence.

“He shall cover thee with His feathers and under His wings shalt thou trust; His truth shall be thy shield and buckler.

“Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night nor for the arrow that flieth by day.

“Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness, nor for the destruction that wasteth at noon day.

“A thousand shall fall at thy side and ten thousand at thy right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee.”

At the reading of each of these verses he exclaimed, “You see, he didn’t get hit.” The contraband [ie, the escaped slave] evidently was perfectly sincere in the belief that if I read this verse before a battle I would never get hurt.

In 1865, Confederate soldier Henry Morton returned to his home in Tennessee, amazed to be still alive. As he wrote,

When I left home three years previously, in the Spring of 1862, my mother had given me a small pocket Testament, on the fly leaf of which she had written ‘ A thousand shall fall st thy side, and ten thousand at thy right hand, but it shall not come nigh thee” (Ps.91.7). It seemed almost like a prophecy, and was literally fulfilled, for in all my war experience, I had never received a wound.

One of the more remarkable (and still insufficiently known) memoirs of this era is that of Levi Branham (1852-1944), born a slave in Georgia, and who survived his later encounters with the Ku Klux Klan. He cited the three scriptural texts that he cherished, and which had allowed him to pass through those menaces unscathed. Those were Psalm 91 (of course), together with Psalm 23, and Ecclesiastes 1.1-18. His memoir concludes with the full text of all three.

Interpreting the War

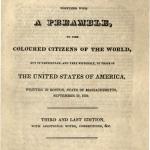

The psalm’s words and imagery inevitably framed understandings of the larger conflict. In a sense, Psalm 91 was the founding text of abolitionism. When the American Anti-Slavery Society held its inaugural meeting in Philadelphia in 1833, its commemorative Declaration included a potent image of a warrior defeating threatening creatures, with the psalm’s v. 13 quoted underneath: “Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet.”

In 1859, after John Brown’s raid, the Staunton Spectator [Virginia] framed the coming conflict entirely in terms of 91:

the people of the South place their trust in a higher power, whose protecting care they expect in time of peril. They believe that an institution of slavery is ordained in Heaven, and that the slaveholder who trusts in the Almighty arm will find that arm a refuge and a fortress. They expect to be delivered from the snare of the Abolition fowler and the noisome pestilence of fanaticism. Truth is their shield and buckler, and they are not afraid of the terror by night nor the arrow that flieth by day.–And in any contest that may arise in so righteous a cause will have an abiding confidence that a thousand shall fall at their side and ten thousand at their right hand, until they come off conquerors.

Our psalm’s v. 6 became a common metaphor for the war and its sufferings. Here is a typical sermon at the start of the war, from Rev. Frederick H. Hedge, in Brookline, Mass., who warned of clandestine enemies within Union ranks:

There never was a conflict so complicated and embarrassing as ours. Had we only the known, declared, and open enemy to encounter, our task would be comparatively light. But we have to contend with secret foes; our enemies are partly those of our own household; Treason lurks in our own ranks, in league with Rebellion outside, and furthering its cause. If we fail at last, it will be the treachery that walketh in darkness, not the destruction that wasteth at noonday, to which we succumb.

(Hedge himself was a leading light among the Transcendentalists). In 1864, Frederick Douglass drew on the familiar rhetorical arsenal when he declared that the Confederacy and its cause “rivaled the earthquake, the whirlwind, the pestilence that walketh in darkness, and wasteth at noonday.”

It is hard to overstate how frequently the “pestilence that walketh” verse appears in accounts of individuals and events, whether we are looking at memoirs, regimental histories, or obituaries: such quotations and recollections could be multiplied almost endlessly. Of course the verse was quoted when Harvard University – and countless other institutions – celebrated the war’s end in 1865.

Pestilence

The words had a special relevance because of the “pestilence” element: as soldiers knew from grim experience, disease was almost as effective a killer during the war as was actual combat. Already in December 1861, a Confederate doctor in North Carolina observed that “our brave troops have suffered very much from sickness. Some, in their encounter with the enemy, whilst defending ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave,’ have fallen victims of the arrow that flieth by day; but a far greater number have fallen to the pestilence that walketh in darkness.” A Union veteran recorded the hideous conditions in the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville: “Making that prison pen a very breeding place for disease and death, where ‘the pestilence that walketh in darkness and the destruction that walketh at noonday’ found no opposition.”

Quite apart from the war itself, literal pestilence was also very common, far more so than we often recall in our visions of nineteenth century US life, and 91 was often used to frame and understand it. Around the English-speaking world, Psalm 91 supplied the images and metaphors that were regularly used for cholera, which launched deadly assaults on the US in 1832, 1848, and 1866. In 1832, Orville Dewey of the Unitarian Church in New Bedford preached on “The Moral Uses Of The Pestilence, Denominated Asiatic Cholera”:

But if there is a Power, beneficent as it is mighty, that stays, at its pleasure, the pestilence that walketh in darkness and the destruction that wasteth at noon-day; if it suffers the prevalence of disease to answer wise purposes; if this calamity, however singular, is, nevertheless, a part of the universal providence; if it is, like all other means for the reform and improvement of the world, to do more good than evil; then surely may we learn to look upon it with calmness and acquiescence.

Alluding to the cholera epidemic of that same year, Cherokee editor Elias Boudinot warned of the dreadful dangers facing his nation at the hands of

an overwhelming white population, a population overcharged with high notions of color dignity, and greatness-at once overbearing and impudent to those whom, in their sovereign pleasure, they consider as their inferiors. … Such a population, and the evils and vices it would bring with it, the chief of which would be the deluging the country with ardent spirits, would create an enemy, a hundred fold more to be dreaded than the unseen messenger of God’s anger, now traversing the earth-‘the pestilence that walketh in darkness ‘ the destruction that wasteth at noon day.’

In 1896, an Iowa writer recalled the horrible cholera outbreak in that state in 1851. He concluded, typically: “What man would not much prefer taking his chances in a bloodier battle than any of the great Civil War to meeting the pestilence that walketh in darkness; this destruction which wasteth at noonday?”

Yellow fever was called the “yellow demon,” with appropriate citations of the psalm’s “noonday demon.” When a yellow fever epidemic struck Mobile, Alabama, in 1853, Methodist minister John Wesley Starr wrote, “The pestilence walketh in the darkness, and the destruction wasteth at noonday. Day and night, more or less, I am visiting the victims of the plague.” (The disease killed Starr shortly thereafter.)

Similar words, with the same verse quoted, featured regularly across the U.S. South over the following decades. When yellow fever ravaged Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1873, one preacher “faced the pestilence that walketh in darkness and wasteth at noonday, until his exhausted strength succumbed to the deadly miasm [sic for miasma].” The same language permeated secular accounts.

Very few of those who used the psalm in this “biblical” way were seriously attributing a given epidemic to supernatural or angelic forces. Rather, the words were attractive because they were so well known and offered an effective rhetorical tool for stressing the potential threat of a particular ailment. The Rev. Starr knew very well that he was not dealing with literal “plague,” but the word carried so much Old Testament freight.

Crisis

When Grover Cleveland was inaugurated as President in 1893, the great financial panic of that year was just beginning, inaugurating an annus horribilis that would closely foreshadow the horrors of the Great Depression of the 1930s, with threats of starvation and open revolution. Presumably conscious of those approaching threats, Cleveland took his oath of office on a Bible opened at Psalm 91: 12-16: “They shall bear thee up in their hands, lest thou dash thy foot against a stone. Thou shalt tread upon the Lion and the Adder; the young Lion and the Dragon shalt thou trample under feet.” Had I been present at the event, Cleveland’s choice of text would not have filled me with any great sense of confidence about the nation’s imminent future, and I would have been dead right.

We really could use the psalm as a lens for understanding many aspects of the social and cultural history of the US in that era. And if you delve into the documents of the American nineteenth century – notably in the Civil War years – you can’t fail to find many more examples. When you know to look for the key words, you will find them everywhere.

And yes, you could do exactly the same digging for many other eras of war, definitely including World War I, and probably the Second World War as well.