“The Americans, having introduced slavery among them, their hearts have become almost seared, as with a hot iron, and God has nearly given them up to believe a lie in preference to the truth!!! And I am awfully afraid that pride, prejudice, avarice and blood, will, before long prove the final ruin of this happy republic, or land of liberty!!!… Will the Lord suffer this people to go on much longer, taking his holy name in vain? Will he not stop them, PREACHERS and all? O Americans! Americans!! I call God – I call angels – I call men, to witness, that your DESTRUCTION is at hand, and will be speedily consummated unless you REPENT.”

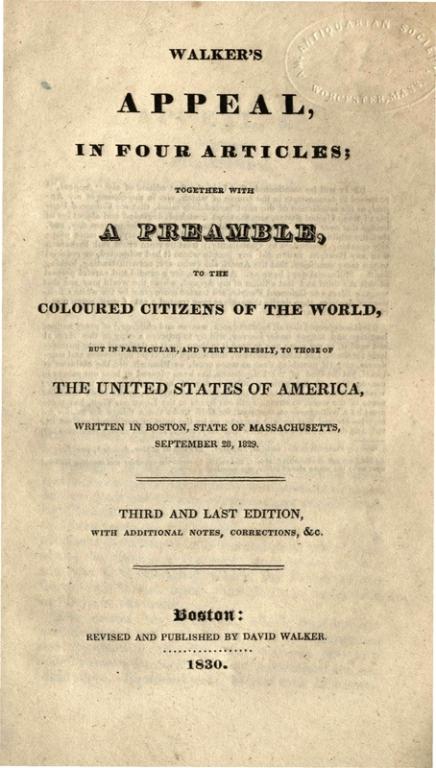

— David Walker, An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World

There are two risks when railing against those who defend the beneficiaries (or more precisely, exploiters) of racialized chattel slavery: futility and polemic capture. On the one hand, it becomes a platform battle: who are you writing to? What do you hope to accomplish? Will we go back and forth on a historical issue merely to reach the stalemate that we have not moved past since the Civil War? Said another way, the historical institution of racialized chattel slavery did not cease because of good arguments; that instantiation of white supremacy ceased because of war. There is the risk of our arguments descending into just so much railing against the wind.

But there is also the risk of polemic capture. One of the most frustrating things to me in general is the fact that polemic often dictates the categories of an argument. Said another way, it is often the case that in arguing with another person, in order to do so, you must argue on their terms, even if those terms are wrong.

Yes, I’m talking about Rev. Kevin DeYoung.

Jacob Huneycutt wrote an excellent short piece for the Anxious Bench that eviscerates the historical claim that slaveholding was a moral “blind spot”, always a rhetorical move to dilute a profound moral evil. But the context of Huneycutt’s piece must be considered: he writes first and foremost as a historian. That is, the great value of pieces like Huneycutt’s piece is that they continue to drive home the fact that those who argue that participation in a system that necessitated manstealing, economic and sexual exploitation was just a “blind spot” rather than a damnable sin do so ignoring the testimony of the enslaved and those with more faithful moral compasses.

But this is only one of the points that needs to be made. After all, opinions about slavery don’t necessarily help or hurt the poor and the marginalized today.

When I write, I write both as a historian and a pastor. I take pains not only to be correct in my historical analysis but also to be clear about how that affects our current moral reasoning and care for our neighbor. To me, this is not so-called presentism. This is love and moral clarity. After all, historians are human beings and for the Christian historian, it is imperative that our methods be Christian. What does that mean? Well, if the central Christian ethic is a care for the poor and marginalized, everything we do ought to further that ethic and nothing we do ought to damage or dilute that witness.

So when I encountered DeYoung’s piece, I thought about it in the context not necessarily of other, to me, annoying, defenses of men and women who did not fight to defend and love my ancestors, but with the added context of DeYoung’s other recent public works, especially his sharp critiques of Beth Barr, Duke Kwon, and Gregory Thompson. That is, good historians recognize, as DeYoung surely does, that an author’s work should be considered within their corpus. In what have amounted to defenses of the patriarchy that Barr names and resistance to the reparations that Kwon and Thompson have forcefully argued for in their excellent book, I have enough data to see a pattern, not of relentlessly coming alongside the abused and exploited, but of defending well-established seats of power. That said, I want to interact with Rev. Dr. DeYoung’s work not as detached, amoral history, but as an act of pastoral care for our readers. Such care requires moral clarity.

As another historical example, one of the things that precipitated my dissertation was the fact that much of the scholarship and conversation surrounding Christianity and lynching focused less on resistance and more on Christianity’s complicity. For example, Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP from 1929–1955, in his book, Rope and Faggot, devoted a full chapter to this relationship, arguing that it’s possible that Christianity, particularly in its evangelical flavor, is the only religion that would allow space for lynching. To him, Christianity was the religion that allowed “colour to be used as a cover and a justification of the emotions of cruelty which religious fanaticism engenders.”

The primary issue with this argument, however, is that it takes white lynchers and slaveholders at their word when they refer to their own Christianity, which then has led to other white, often Christian scholars to ask the question: how could they do these things and still be Christian? It is this question that then leads to statements about moral “blind spots”: somehow the faith of those in flagrant, public, unrepentant sin must be justified and the answer often is, “Well, they didn’t know any better.”

I find that argument to be woefully inadequate, morally reprehensible, and historically unfounded.

In the case of lynching and elsewhere, the important voices are not the morally compromised ones. Though they are historically relevant, in the sense that all voices are, they are morally so only insofar as they are to be strenuously resisted. We must constantly discern which voices we note and which voices we heed. The voices to heed are the morally clear ones like those of Black Baptist and Methodist ministers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who, as Mary Beth Mathews has noted, “contended that lynch mobs, and indeed all white segregationists, were not Christian and instead were in league with the devil. There was no religion at the lynching tree, they argued, only evil.” It is not enough to frame lynching, racialized chattel slavery and other violent and exploitative instantiations of white supremacy and racialized capitalism as “un-Christian” or “moral blindspots”. They are anti-Christian, fundamentally contrary to a faith that, in affirming the incarnation, life, death and resurrection of the eternal Son of God, draws solidarity with the poor and oppressed into its very definition. Wracking your brain about how lynchers or slaveholders can be Christian is a waste of your time and energy.

It is better by far to seek to do the hard work of determining the ways in which you can robustly and clearly resist the assumptions, justifications, actions and material investments that propped up and continue to prop up such exploitation and violence.

Better by far to focus your moral energy on those who saw (and see) clearly.

For the lynching era, those were most often Black Christians. In the era of racialized chattel slavery, voices like that of David Walker were not extremist or moral geniuses. Frankly, the voices that called for immediate emancipation were the voices of moral clarity. Such clarity was difficult, of course, in a political economy that depended on violent sexual and economic exploitation. But that difficulty does not reduce its necessity.

How do you avoid futility? Ask the question of how this work helps me support the needy.

How do you avoid polemic capture? If you are a Christian, remain committed to the center of our ethic: care for the oppressed, those oppressed by both human and infernal empires.

So next time you see a defense of a slaveholder, keep these things in mind. It may be relevant to note, but it is not relevant to heed. Most important is your moral and practical formation and if anything dilutes a deep revulsion against exploitation, it is best avoided. For now, finding the morally clear voices in today’s culture and political economy is the task at hand.