When I was pregnant and finishing my dissertation, a beloved dean told me about one night when she was writing hers. Her husband decided to take the kids out for ice cream, but she couldn’t go because she had to finish a chapter, so after he piled them in the car, she put her head down on the table and cried. She told me this as an encouragement–one day you too will be cleared to go out for ice cream!–but I’m not sure the moral of the story is that clear.

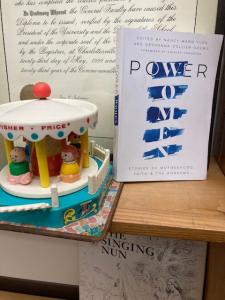

The puzzle of putting together academic work and motherhood is the task of a 2021 book, Power Women: Stories of Motherhood, Faith & the Academy. The book grew out of fruitful conversations among women at a Christian university in a “Professor Mommy” group. The essays argue that academic work is compatible with motherhood in a fully rounded Christian vocation. Presuming that readers will agree, the writers offer some suggestions for support.

Readers remote from ivory towers or Christian-college quadrangles might be hard pressed to see where the catch is, what the problem is to which this book seeks solution. The chapters get at the trap set by unrealistic expectations of American motherhood, stresses in higher education, and favor given to stay-at-home moms within some evangelical and Protestant communities. Until fairly recently, conservative-ish Christian circles hardly took for granted the desirability of women’s careers, academic careers included. Most of these writers entered the academy on the far side of that watershed. But the former shape of that landscape still colors the prospects of the “Professor Mommy” writers in the book, and addressing that past directly would offer stronger solutions for the future.

Shirley Hoogstra, President of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities (CCCU), offers a foreword to the book. Noting that she knew her husband had a “medical calling” as a doctor, she explains with equal certainty that she had a “certain calling” to be in legal practice: “I was good at it. I was serving others. I had a Christian witness.” The implication for academic women is this: if God has called you to academic life, which you know because you are good at it, and can serve others that way, and provide a witness, you ought not, Jonah-like, to try to evade the call. She warns readers, “God’s vocational call on your life needs to be honored….we are not to hide our talents in the ground. We are instructed to multiply them for the good of the kingdom of God.” Thus, women struggling to balance family life and academic work should keep on, pressing on to the prize of God’s future declaration over them, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

Something in this exhortation clangs against echoes of the past. The situation here is not just that being a working mom is challenging but rewarding, or that being a good mother is possible while doing a good job in one’s worldly service, or that academia can accommodate committed Christian women. True, those. But the situation these writers confront emerges out of a long American past where women were discouraged from academic work, and out of an influential strain of American Christian culture that, for its own distinctive reasons, also discouraged women from this kind of work. The old reasoning against Christian women planning careers was that their skills would be needed elsewhere–wife and mother–so although academic work was not ruled out, a field whose jobs were structured around singleness or the presence of a wife at home was hardly the most obvious course.

I knew women in graduate school in the 1990s, including some who also showed up at the Grad Christian fellowship, but the provisional character of these ventures was not just my imagination.

Recent commemorations of George Marsden’s Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship and Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind recall heady days when I would go with my husband, from the same history graduate program, to gatherings of young Christian scholars. There were some women in these groups but men were the majority, committed Christians and excellent scholars, who would fall to talking about a common text or a trend in their discipline while wives would cluster in another room or oversee children. In these circles men tended to do one job and women tended to do another one.

The implication was that if young women who took seriously motherhood also saw a call to prioritize a career, a kind of special pleading was needed to justify time away from right demands of family and ministry. Maybe a specific kind of research and teaching had to be done, and circumstances, or Providence, had arranged it so that this particular woman had to do it. It wasn’t the usual manner of Providence, but some women had this call and were capable of answering it, kind of H-1B status for special Professor Mommies. For PhD candidates in humanities fields in late-twentieth or early twenty-first centuries, though, this was a hard case to make. The provisional character of these ventures, women stepping out to do what women not long before did not do, felt even more provisional in light of what women were stepping out into: a job market unlikely to offer a spot for even very distinguished candidates. Those job markets have not mostly improved.

At some point (maybe not announced at the same time everywhere), academic jobs became an additional thing women could do if they chose. Women academics became more common. The new permission–you could do this too–came by accretion, a job that moms could add to the ones they were already doing. But Hoogstra’s packaging of that vocational combination carries a bite that even secular having-it-all expectations don’t. The Christian woman gets this task overload as a charge from God.

Professor Mommies might construe their work that way, or their loving service and relationships as wives, mothers, neighbors, but I don’t think that job description is authored by God.

Appropriately, the essays in Power Women do struggle with the vocational combination. They help academics feeling judged by American motherhood standards to recognize the absurdity of those standards (Christine Lee Kim), or substitute the job description applied to dads for what moms are supposed to do (Ji Y. Son). Kim’s critique is especially apt, rejecting American idealizations not from secular sources but from the wisdom of a different Christian tradition. Her Korean mother scolds her, warning that to forsake professorship to stay home with kids would be cheating church and community out of gifts that God gave her to use. Teri Clemons’s chapter handily dispatches suspicion that academics on maternity leave are secretly using the time to loll about or get ahead with their publications. The reader might nod yes, academic work is compatible with motherhood.

But is there really a “synergy of lullaby and syllabi,” as Stephanie Chan’s chapter wittily purports? I maybe could argue that rearing children enhances my sensitivity to students’ emotional needs or that teaching students gives me fresh strategies for motivating my kids. I admit to sometimes occupying a mom-ish role in classrooms and to seeing students as some mother’s child, though I never tell them that. And academic calendars can accommodate family life, weekly flexibility plus summers off, a version of what used to be pitched as “mother’s hours” in a workplace. Some faculty women teach in disciplines immediately pertinent to family life. History is pertinent to everything and everything to it. I guess I see some synergy.

Good babysitters abound on campuses. Once I had one who thought it best to keep my nursing baby nearby, so would take him, loudly crying, for walks outside of my classroom. Academic also work gives you options if childcare falls through: you can bring your children to class and set them up in the back of the room with crayons or seat them in the hallway with an edifying video. If disaster strikes and you need to cancel a class, it’s no great disaster, and now there’s Zoom.

That’s the up side. This flexibility has a down side too. Academic work, like that other kind associated with women, is never done, and some calculator multiplies at-home tasks for every hour spent in class or office. This work has no built-in quitting time. If you have the kind of job where work time is regular, in office or classroom, you might do your work during the day and leave it there. The bleakness and competition of the current academic job market turns up pressure. Professor Mommies might feel the double bind. What makes the work flexible also makes it insatiable; because the work can be done at home as well as in office it resists being left behind, ever, especially for workers whose normal business hours are interspersed with childcare and hours that come due once children are in bed. So much for synergy.

Near the book’s end, proposals come for policies that might enhance the synergy. Campus supports, mentoring programs, and self-care should go some distance. We might expect the church-related institutions where some of these writers work to be more progressive, more family friendly, than hyper-competitive ones. After all, those institutions uphold ideals of excellent scholarship and sound family life. The strains on small colleges–tuition driven, cash-strapped, bent low by economics and demographics–to make good on some of these goals comes out most clearly in Yiesha L. Thompson’s chapter, “A Principled Discussion for Adjunct Professor Mothers.” Thompson finds ways even small changes, like flexibility with mandatory meetings, can do a lot. The rub of Thompson’s plaint is revealed in her phrasing, as she considers how deans can help “contingent mothers.” She means contingent faculty who are mothers, of course. But the phrasing is revealing.

At their best, these essays address not only the vocation of the Professor Mommy but of Christian colleges that employ them. Inspired by their own principles–the unity of truth, the importance of working unto God, and the good of family life–these colleges might be able to do better than other colleges and universities minus those motives. Christian colleges animated by these ideals could prompt reform, departments rewarding the kind of service to family, society, and community these women demonstrate.