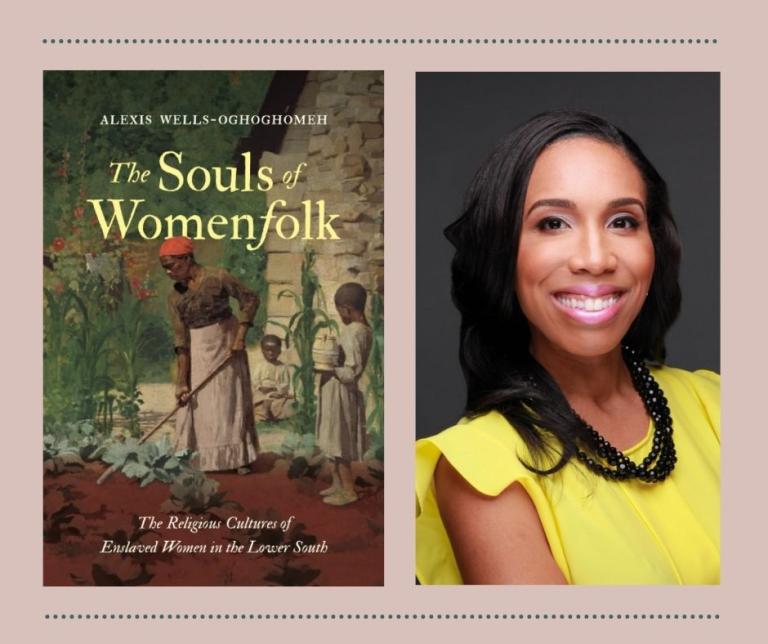

How did gender shape how African American women experienced religion and enslavement? As we shift from Black History Month to Women’s History Month, I took the opportunity to consider the intersection of both fields and interview Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh, Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Stanford University and author of The Souls of Womenfolk, published by the University of North Carolina Press this past fall.

Together we discussed her research on the distinctive religious cultures of Black women during slavery. Beyond that, we talked about the opportunities found in engaging in multiple scholarly fields and the challenges of researching and writing about communities who are not well represented in traditional archives. More than anything, we reflected on the ethical obligations associated with doing work on a painful and highly personal topic. “These histories are my histories,” said Dr. Wells-Oghoghomeh. “I am of the blood of people who experienced this. So in a lot of ways, it motivated me to tell the story right.”

The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Melissa Borja: Tell me a little bit about how you came to write this book.

Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh: The Souls of Womenfolk is emerging out of my love for Africana religious history and slavery history. When I was in graduate school, I started doing a lot of work alongside Leslie Harris, who was a slavery historian. I started to see in the histories of slavery that you had this wonderful development of work around how women’s gendered experiences configured how someone experienced the institution of slavery. However, in those very same books, there was very little engagement with religion. Religion oftentimes was understood as this institutional formation–usually Afro-Protestantism or maybe conjure–and it was glossed over quite frequently. A lot of slavery historians don’t really deeply engage religion. I can name a few who do it, and they do a fantastic job, but still, it’s not very heavily engaged.

And then when you come over to Africana religions, we have these wonderful monographs on religion and slavery. Not as many as we should, but we have some, and the ones we do have are really fantastic. But there is no engagement with gender whatsoever, or, I should say, very little engagement with gender. So the combination of the two made me see this potential, this lacuna in the field that could potentially be addressed through a serious interrogation of the types of sources where we find women. So that’s where The Souls of Womenfolk came from. I was inspired by the works that I had read in both fields, but I was also motivated by the voices I didn’t hear.

MB: Could tell us about the main argument in your book?

AWO: Sure. The main argument is that enslaved women have religious cultures that were distinctive to them because slavery itself was a highly gendered experience. One of the main premises of the book is that religion is embodied. We say that all the time, I think, in religious studies. But oftentimes we don’t write it using methodological approaches that takes seriously the material conditions of people who are practicing religion and who are birthing religion. And so one of the things I wanted to do with this book was create an embodied religious history, one that considers the material realities of gendered women who found themselves within this institution and trapped within these coercive systems, and how they imagined the cosmos, how they made ethical decisions, how they did things that were necessary for their survival, basic things like how they named their children and more exalted things like how they thought about death. I was interested in the transcendent and the mundane in this book. I think the subtext is we have to take seriously the material realities of slavery if we are going to understand the consciousness and the experiences that birth Africana religious history in the United States.

MB: That focus on the material conditions of slavery and the embodied experience of being an enslaved woman is right there in the very beginning of the book, in a very visceral way. I have to admit: when I read your book, it was painful to read, partly because I was reading as a woman and as a mother. What was it like to do this research? And how did you do the research?

AWO: First, how you experienced that opening of the book–that was the intent. How I approached it really was thinking about what needs to happen for the reader to understand the consciousness that created this religiosity. Because I’m thinking about things like filicide, because I’m thinking about really complicated issues like sexual coercion and non-consensual sexual encounters, I’m threading the needle through all these very difficult topics, and so I needed the reader to situate themselves in these women’s bodies, and I needed you to connect with them as a woman, as a mother, as whatever it is that connects you as someone who has family, as someone who is lost, or as someone who is estranged from their home nation, whatever positionality you find yourself in. I needed you to situate yourself so you could connect with the many layers of human experience that they were having. I said, first, that I have to tell the story of the materiality, and I have to create and write in ways where people are witnesses to what’s happening to these women. Because if you’re not a witness, if it doesn’t feel like you’re there, then I think it’s very difficult to make the intellectual shift to some of the things I want to claim are religion and are sacred.

When I first started to write the dissertation that became the book, I had no kids at the time. But over the period of time between chapters one and three, I got pregnant, and I had a baby, and that completely changed my orientation to the materials. When I was reading these primary sources where these women were hearing their babies cry and could not get to them, and their breasts were leaking, and they were out there being forced to stay away from their children, I felt that on a visceral level. And I felt why if you have that experience as a woman, with your first child, with your second or third or fourth, you may say, ‘I’d rather not.’ I got it as I was holding my own newborn and knowing how it felt for me in my own body.

The experience of writing was one that was very personal. I am the descendant of enslaved people here in the U.S. All of my people who were enslaved in the U.S. were in the Lower South and also in the Caribbean. And so these histories are my histories. I am of the blood of people who experienced this. So in a lot of ways, it motivated me to tell the story right, or as right as I thought I could. It’s about my ethical commitments to my community, and for me, my commitment to my community was to humanize the women that I told these stories about, so that you can see them as individual human beings with hopes and dreams and desires that were muted in our archives and in our national memory.

So I went and just looked for enslaved women in all these very quiet and mundane places. I’ve said this over and over again, but it’s the best metaphor I can use: they are always background figures in the archive. You have Linda Brent (a.k.a. Harriet Jacobs), but she is such an anomaly. Most of the time it is Frederick Douglass and other male figures who are able to voice how they experience slavery. But we don’t have women very prominently in the archives talking about these things. Those voices are just so distant–they’re like echoes and phantoms in the archive.

MB: I think this is the most powerful part about your book: the degree to which you center the dignity of enslaved women and center their experiences. It really is clear to me that you bring a deep love for the people and the community at the center of your story, and that is really powerful to me and very inspiring. It makes me think about how we could all learn from that example of carrying into our scholarship that ethical commitment to the human beings whose stories we’re hoping to tell. I would say that is the biggest intervention in my view, but there are other historiographical interventions that I think your book makes. It’s a very ambitious book, so let’s talk through the interventions you make in each of the three fields that you engage. Tell me how your book helps us rethink the history of slavery in the U.S.

AWO: So for the history of slavery in the U.S., I hope it helps us to take religion seriously. I would like this book to help historians of U.S. slavery understand how religion enables us to access questions of interiority that are not easily accessible through any other intellectual category or methodological framework. I’ve used the word transcendent, but it’s transcendent in a very intellectual way, in an ethical way, and in an everyday way for people who are practitioners or who live within cosmological and ethical or philosophical worlds that might now be termed religious. So that’s the primary intervention: I would like there to be more attention to religion. I don’t expect people who aren’t trained heavily in religion to all of a sudden just shift to doing religion, but at least to read religious studies scholars who do take the category seriously and who are trained very well to think about this category in really complex ways.

MB: Let’s talk about religious studies now. How do you think your book changes the field of religious studies?

AWO: My primary conversation partners in religious studies are people in American religious history and Africana religions, and I think in both fields, I’m redressing the historiographical exclusion of enslaved women and the sense that we use the category of ‘slave religion’ without nuancing it at all. And gender is just one way to nuance that category. Enslaved people were different because they were from different places. They had different work cultures. There were different elements of identity that differentiated the experiences of enslaved people and who they were intellectually. And so, in many ways, I’m trying to write against the monolith of ‘the slave.’ I think that would be an intervention across the fields that I’m trying to make. Because the methodologies are not examined as critically as they need to be, sometimes we don’t get a high level of differentiation and individuality.

MB: We are beginning Women’s History Month. Could you explain how your book helps us rethink women’s history in the U.S.?

AWO: In many ways, enslaved women are not a part of women’s history in the way we mark women’s history as a field. I think you have people who have done a fantastic job theorizing methodological approaches to history that allow for an examination of a broader range of people who are identified as women in the U.S. However, I think we still struggle as multiple fields against this impulse to highlight people who are more visible in the archive, and visibility can translate into just the types of records they leave. Even if we’re looking at diaries which have long been one of the sources that have granted historians access to more ‘everyday women,’ The Souls of Womenfolk highlights women who did not have the means to sit around and write a diary. One of the ways it speaks back to that canon is by saying, look, there are women in our society whose labor enabled those types of sources to be created, and those women deserve histories, too. They deserve not just historical narratives that are tied to the women who are writing the diaries, but ones that center their experiences, their voices, and their ways of moving through the world. And that requires different methodologies.

One of the things I’m really interested in is being in more conversation with people who are interested in the study of anybody whose voices have been marginalized in the archive. The Souls of Womenfolk is, I think, just one small step towards that conversation about methodology and how we do the work and how we consider archives and the kinds of sources that count as legitimate or valid. We oftentimes invalidate sources where we find a lot of those marginalized voices and the voices of women whose identities intersect with other kinds of marginalized groups.

MB: One thing that’s amazing about your book is you do a project that, as you suggest, people often think is not possible because of the absence of sources, and you’re encouraging us to think imaginatively about the different ways we could do this type of scholarship. I see your work as making an intervention not only in what we know, but how we can imagine what is possible to do as scholars. I really appreciate that.

So what other projects are you working on next?

AWO: Well, I hope to soon have out a methodological article about the category of slave religion and what it would mean to write gender into this history. But the next big project is thinking about the phenomenon that has been termed witchcraft. I’m really interested in how this category has assumed a racialized and gendered life in the history of the U.S. Even though there is a wonderful and quite robust historiography around American witchcraft, women of African descent and indigenous women really don’t extend beyond the figure of Tituba and Salem. So I think I’m making the argument that the category of witchcraft continues to haunt the religious practices of indigenous and African-descended women for many generations after Tituba. I’m interested in the intellectual and social life of this category and how it’s been deployed to racialize and gender certain religious practices and certain people’s embodiment in said practices.