Husezo Rhakho is a doctoral student in the Religion Department at Baylor University. He holds a BA in History from Patkai Christian College, an MDiv from Kohima Bible College in Nagaland, India, and a ThM in Christian Thought (World Missions/Global Christianity), from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. He studies World Christianity and History of Christian Mission, particularly in Asia. His research centers on the trends and growth of Christianity in the global south from an insider’s perspective.

He comes from Nagaland, in north-east India, a region that over the last century has been the subject of intense and successful Christian evangelization. Today, it is proportionately the most Baptist area to be found anywhere. Not long ago, I wrote about Nagaland in Christian Century under the title “More Baptist Than Mississippi.” Husezo here tackles a very interesting topic, about the clash between that new Christian attitude and older local cultures, specifically in the matter of alcohol. But I am particularly glad to see this piece because it addresses a topic close to my heart, namely the gap between older and newer evangelical cultures around the world. Not long ago, what Husezo describes as the Christian Naga attitude to Temperance would have been (at least officially) the standard expectation in many or most American Baptist circles.

Temperance Abroad:

A Tale of the Temperance Movement in the Most Baptist Land on Earth

Husezo Rhakho

In Nagaland, where I was raised, drinking alcohol was considered a sin and a social taboo. The Baptist church there and various societies spearheaded the temperance bandwagon for a Christian Utopia. I always imagined America as a Christian country because of the work of the missionaries who came from America and made my land one of the most Christian provinces in Asia. But when I arrived in America for my master’s studies at a seminary, I was surprised to find out that my seminary friends and professors drank and smoked. They had no remorse, guilt, or shame; instead, they were proud of it. I was taken aback and amazed: Where did I land for my seminary education? And I started to question myself: Am I really in a seminary or symmetry? Later, I found out how most Christians in America have no problem drinking alcohol. I realize how religion and its practices look very different with time, place, and space. This blog will present how the temperance abroad in Nagaland, North-east India played out and how material things like food and drink shaped religious identities.

In Nagaland, today, almost every Naga identifies themselves as Christians. The Nagas are popularly known for their transformation from “head-hunters to church planters.” The conversion and transformation the Nagas did not come easily. It was filled with pain, genocide, wars, and Christian revivals.

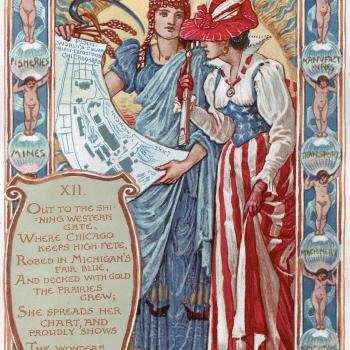

The temperance movement, rooted in America’s Protestant churches, drove one of these revivals. In America, the movement first urged moderation, then encouraged drinkers to help each other resist temptation, and ultimately demanded that local, state, and national governments prohibit alcohol outright. After the civil war, women blamed men’s drinking for domestic violence and misusing family resources. Immigration was a severe issue caused by the rise of alcoholism as well. By the 1870s, stirred by the rising anger of Methodist and Baptist clergymen, and by troubled wives and mothers whose lives had been ruined by the excesses of the saloon, thousands of women began to protest and organize themselves politically for the cause of temperance. Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) became a force to be reckoned with. This era’s temperance movement also influenced most Baptist missionaries, and they imported this teaching into the Naga soil.

In Nagaland, historically, the consumption of rice beer, an indigenous Naga drink, was shaped by their customs and traditions. It was not understood as immoral or had any gendered restrictions in the Naga society. It was a drink form, just like other cultures have tea and coffee. Missionaries often categorized the Nagas into actual or nominal converts, checking to see if they could meet the new Christian standards. Missionaries used total abstinence from alcohol as a baptism prerequisite for new converts.

In her book, A Corner in India, which was published in 1907, the American Baptist missionary, Mary Mead Clark describes how missionaries viewed alcohol as a part of their work in Nagaland. Mary Mead Clark was the wife of E. W. Clark; together the Clarks were considered the missionaries who laid the foundation of Christianity in Nagaland and are highly regarded. In her mission report, Clark mentions that “Every form of demon worship, open or suspected, was attacked – Sunday breaking, rice-beer drinking, licentiousness, and all social vices.” Clark emphasizes that they were fighting the social evils prevalent in Nagaland, naming rice beer, how evil it was, and the need to abstain from it. It is apparent the extent to which the missionaries perceived alcohol drinking as a sin.

But rice beer was central to Naga agriculture, tradition, feasting, and ritual identity. On every public occasion, rice-beer drinking was part of a celebration and considered a gift from God. Nagas regarded rice beer as therapeutic and possessing medicinal qualities. There are various types of rice beer; it can be sweet and some bitter. The most common is white in color, and its thickness can be altered depending on the amount of water one adds to it. The less water, the purer and more potent. It is deemed as a pure drink and thus appropriate for rituals. Its purity is ascribed to the exclusion of any fermenting agent because of the ingredients are from rice. Nagas gathered and worked together in the fields where drinking is often associated with work.

Mary Mead Clark reports on the success of the temperance teaching: “But prayers prevailed, and they came forth unscathed through these days of trial. When called to work where the rice beer was served, they withdrew from the crowd and ate their midday meal by themselves; and when they called the neighbors to harvest their corps, no beer was served.” Working together (Miile Zii in Chakhesang Naga) in the fields is common and a cultural tradition that is practiced till today in Nagaland. Refraining from these groups working together was not just about abstaining from drinking alcohol, but it also meant a separation of relationships among different peers and families in the Naga society. Naga Christians obeying the missionaries’ teaching on temperance had to pay considerable costs in the form of losing their culture and community in the society.

Missionaries, then, viewed rice beer as a strong barrier to conversion. An outward profession of faith or baptism was not enough to show the authenticity of conversion. V. K Nuh, a prominent Naga Church historian, notes that American Baptist missionaries such as Dr. Clark, Rev. Rivernburgh, and Rev. Pettigrew made total abstinence from drinking local rice-beer from the beginning of their mission work as an essential condition for baptism and admission in the Church membership.

Amidst the Indo–Naga political war, Nagas joined the union of India in 1963; the government of India supplied a considerable quantity of liquor as “Political Rum” as a political tool to influence the Nagas. There were more licenses to open many wine shops, and there was a surge in the rise of consuming liquors that were imported from India. The influx of new alcohol, different from the local rice beer, created more tension in the church and society. In the way colonials used opium in China to control the Chinese, alcohol was used as a means of power by the Indian government to control. Recognizing the problem of alcohol as not just a moral issue but as a political and colonial tool to lure the Nagas, Nagaland churches and various women’s groups stood up with slogans that said, “Nagaland will never be a Wineland but a Promised Land.’” Around five thousand Naga Christians demonstrated in a massive hunger strike and protest rally in March 1989. By March 15, 1989, Nagaland Baptist Church Council won the fight against liquor and declared Nagaland as a Dry State which legislated the Total Prohibition of Liquor in the State.

The Total Prohibition of Liquor in Nagaland started with utilizing recognition as a tool of the government of India to influence the Nagas to join the Indian union. The temperance movement in Nagaland can be seen as an agency of power by the missionaries and Indian colonizers, both in a complicating way. The missionaries prohibited drinking rice – beer for indigenous Nagas, and the Indian government supplied alcohol as an agency to control Nagaland. Both proved to be vicious in using their powers to suppress and control the Nagas in the name of religion and politics.

The temperance movement came to Nagaland as an American missionary enterprise, which created a challenge and resentment for the Nagas to their traditional drinking rice beer practice in the late nineteenth century. After decades, in the 1970s, the temperance movement among Nagas became even stronger. It took the form of Naga resistance against the exploitation by the government of India’s supply of liquor. Hence, the dynamic of power and resistance followed by temperance abroad. Christians in Nagaland today are very much against drinking alcohol not just because of the social evils, but because of their theological convictions of seeing drinking as a sin, an idea that was brought to them through the missionaries.