Grove City College, a small liberal arts institution in Pennsylvania, has been in the news. Its Board of Trustees recently released a report investigating allegations of “mission drift.” Because Grove City identifies as a Christian college and I am a Christian historian of religion in American higher education, I read this report with interest.

But the mission drift in question turned out to be much more about the school’s political identity than its religious one. Let me explain.

Grove City identifies as a “conservative Christian college.” (This is the subtitle that comes up for the college if you run an internet search for it.) It’s an ambiguous phrase. It can refer to theologically conservative Christians, in the sense of historically orthodox Christians. Or it can refer to politically conservative Christians, in the sense of Christians holding a range of theological beliefs who all vote Republican. The report makes it clear that Grove City’s Board means the latter.

The Board’s investigation was prompted by allegations that the college endorsed “Critical Race Theory” or “CRT.”

These allegations were enumerated in a petition submitted to President McNulty in November by parents and former students, in a second petition in December responding to his reply, and in an open letter by some anonymous faculty members in February. Together these statements alleged that resident hall directors, chapel speakers, one particular course, and the Office of Multicultural Education and Initiatives had all recently taught CRT. They further alleged that doing so violated the college’s stated mission.

The Board’s investigation, conducted by six white Board members (verified by internet search), concluded that CRT had in fact been taught, though not as extensively as feared, and that it violated the college’s mission. It suggested various forms of redress and noted those already taken.

To understand this conclusion, we need to unpack two things: (1) what the Board understands CRT to be, and (2) what the Board understands the mission of Grove City to be.

First, what is Critical Race Theory?

There are two ways to answer this question: what the term originally referred to, and how the term is now widely used within some Christian subcultures. Originally, Critical Race Theory referred to a specific legal theory that analyzed society in terms of racial power dynamics. But frankly the term now gets used as an aspersion that refers to any type of racial justice advocacy understood to endorse solutions that would fall to the political left of the speaker.

In its most extreme and increasingly common form, the latter use of the term labels as “CRT” and hence “bad” any belief that structural or systemic racism exists in the United States today. And indeed both the petitioners and the anonymous faculty use this definition. The second petition, referring to a TED talk by prison reformer Bryan Stevenson used in chapel, states that “Stevenson, while likeable and softer than popular CRT activists, nevertheless highlights structural racism….” The anonymous faculty complained, “Grove City College administrators and staff advocated for ideas central to CRT, such as systemic racism….”

Note what’s happening here. Instead of contesting the viability or effectiveness of specific proposals coming from the political left to redress racially unjust social structures inherited from our forebears—and offering alternative ones from the political right—some politically conservative Christians assert that claiming that the problem exists at all is anathema.

The problem with this claim is that structural racism is a historical and sociological fact. How best to address it, on the other hand, is up for debate in the same way as what to do about any social problem is up for debate. And having that debate would be productive! But increasing numbers of politically conservative Christians are shutting down the conversation before it can even start.

Strikingly, the Board’s report—unlike the various petitions and statements by Grove City stakeholders—never defines CRT, despite the fact that CRT is the subject of the report. Instead, it lists a series of perceived negative effects of this form of analysis. This omission is our clue that the report is using the second, functional definition of CRT as any form of racial justice advocacy that proposes solutions to their political left. Understanding why they believe CRT to be evidence of “mission drift” therefore requires understanding their answer to the other question:

Second, what is the mission of Grove City College?

According to the report, the Board itself reframed the mission is 2021 to attempt to make it clearer, but fears it introduced confusion. Here are the changes:

Grove City College strives to be the best a highly distinctive and comprehensive Christian liberal arts college in America of extraordinary value. Grounded in conservative permanent ideas and traditional values and committed to the foundations of free society, we develop leaders of the highest proficiency, purpose, and principles ready to advance the common good.

I would offer that the changes to the first sentence seem wise and realistic. The changes in the second sentence leave the mission statement just as unclear as it started. What are “permanent ideas and traditional values”? And what are “the foundations of free society”? Republicans and Democrats would both embrace the second phrase but would mean some different things by it. Meanwhile, care for the poor and equal access to the ballot—more central concerns for Democrats—count as permanent ideas and traditional values, even if that phrase more often connotes historic religious orthodoxy and heterosexual marriage—more central concerns for Republicans.

But while the meaning of the mission statement therefore remains foggy, the revision process publicized here actually clarifies it: “conservative values” was exegeted not with religious buzz words but with political ones, such as “foundations of free society.” The college intends “conservative” not to modify “Christian” theologically, but rather to add to it a second and distinct political identity. The Board report asserts, “GCC remains one of the most conservative colleges in the country,” and in support it cites the college’s high ranking on both the Young America’s Foundation Top Conservative College List and Newsmax’s 40 Best Colleges for Conservative Values. Both of these lists explicitly mean “conservative” in the political rather than the religious sense.

Grove City is therefore a “conservative, Christian” college, not a “conservative Christian” one.

And this is why “CRT” is such a concern. The anonymous faculty make this particularly clear:

The ideological questions raised by this controversy may require a degree of deliberation, but the business dimensions involved are quite simple. While the overwhelming majority of colleges and universities in the United States are liberal in their outlook, Grove City College has stood as a conservative alternative. Parents have rewarded this principled commitment by sending their sons and daughters to the College, often making greater financial sacrifices than would be necessary at other institutions because Grove City College does not accept federal funding.

This is the College’s brand in the marketplace, and we expect its position will strengthen as families continue to seek educational environments where their sons and daughters will receive a high-quality academic experience without being subjected to hostile philosophies and social experimentation. However, this will require faithfulness to the College’s historic mission and identity. The way President McNulty and his leadership team have handled the current controversy has tarnished the College’s status as a trusted conservative alternative and has eroded commitment and goodwill among the College’s core constituency. Unless trust is rebuilt, the College’s enrollment and financial well-being will be negatively impacted.

Note that this decision-making paradigm says nothing about either the Christian identity of the college or the rigor of the education offered. It evaluates the role of racial justice education labeled “CRT” not in terms of how it contributes to or weakens the Christian formation of students or how it contributes to or weakens their intellectual development. Rather, it evaluates these initiatives in terms of how they contribute to or weaken the college coffers.

To be honest, that’s a real bind. No Christian college can contribute to the Christian or intellectual formation of students who won’t attend, and it especially can’t do so if it goes bankrupt and ceases to exist. As Adam Laats has demonstrated in his excellent book Fundamentalist U, Grove City therefore stands in a long line of fundamentalist and evangelical colleges that must convince their constituents that they are “orthodox” in whatever ways the donors care about that decade, but without the benefit of a formal hierarchy to which to appeal on questions of belief or practice. But it’s a bind because this paradigm prevents Grove City from most effectively educating the hearts and minds of Christian students.

To be honest, that’s a real bind. No Christian college can contribute to the Christian or intellectual formation of students who won’t attend, and it especially can’t do so if it goes bankrupt and ceases to exist. As Adam Laats has demonstrated in his excellent book Fundamentalist U, Grove City therefore stands in a long line of fundamentalist and evangelical colleges that must convince their constituents that they are “orthodox” in whatever ways the donors care about that decade, but without the benefit of a formal hierarchy to which to appeal on questions of belief or practice. But it’s a bind because this paradigm prevents Grove City from most effectively educating the hearts and minds of Christian students.

Let’s conclude by considering how this problem played out in two of the CRT incidents highlighted in the Board’s report:

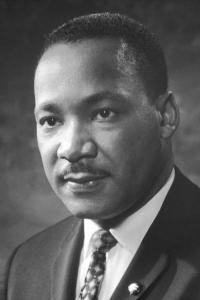

The first is the chapel talk given by historian and theologian Jemar Tisby in 2020. This talk merited an entire page of the report. The Board accused Tisby of including “divisive racial themes” in his talk, but, fascinatingly, declined to state what those were. In fact, the report declined to engage with the content of Tisby’s talk at all. It only said he shouldn’t have been allowed to speak in chapel because he elsewhere advocated “progressive” policies. (Tisby has since issued a response.)

I listened to all 21 minutes of this talk and am better for it. I would estimate that a full quarter of the talk consists of quoting Scripture and quoting Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The rest of the talk consists of some itemization of contemporary injustices faced by Black Americans, especially violence at the hands of some police officers, and a challenge to the students—many of whom Tisby notes would fall into the “white moderate” demographic to whom MLK wrote “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”—to not sit idly by like their forebears did.

The only “action point” of the talk was to urge students to educate themselves. Tisby did not advocate a single specific political policy. He advocated that students make sure their college education involved grappling with the continuing racial injustices in the U.S. and then deciding for themselves as Christians how best to respond. This is what the Board dismissed as CRT. If fear of guilt by association with someone to their political left means this message is not welcome in Grove City’s chapel, the Christian formation of students there will be impoverished indeed.

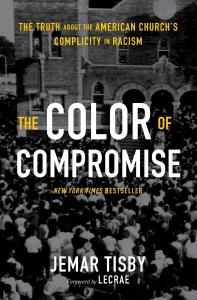

The second example is more mixed. Petitioners complained about the reading list in a course in the education department that consisted entirely of works written from an “anti-racist” philosophy, a particular approach to redressing racial injustice. Books included Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates; White Fragility, by Robin DiAngelo; and How to Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. Kendi. The petitioners’ complaint was that they considered this approach CRT. To their credit, they did not want the books banned from the classroom, but rather paired with other texts that took a different view on the nature of race relations in the U.S. today—and for the professor to explain why CRT was wrong.

At the Board’s urging, President McNulty agreed to replace the course with an elective “interdisciplinary course, designed for all students, and residing in an appropriate department as determined by the administration, that considers this controversial issue in light of the College’s vision, mission, and values.”

In the best case scenario this course could be healthy for the college. Even criticisms arising from flawed assumptions can have value, and it’s a fair point that a classroom is enriched by reading that does not all come from one ideological space. The petitioners would seem to want the professor to come down on the side that structural racism does not exist or to assign books that state this claim, and this approach would not be intellectually viable. But if instead the professor assigned books that creatively address racial injustice in a variety of different ways (including but not limited to the “anti-racism” school of thought) and then allowed students to work through how their Christian faith informs their response to this issue, then the students in this class would be given the opportunity to do exactly what Tisby urged.

In the best case scenario this course could be healthy for the college. Even criticisms arising from flawed assumptions can have value, and it’s a fair point that a classroom is enriched by reading that does not all come from one ideological space. The petitioners would seem to want the professor to come down on the side that structural racism does not exist or to assign books that state this claim, and this approach would not be intellectually viable. But if instead the professor assigned books that creatively address racial injustice in a variety of different ways (including but not limited to the “anti-racism” school of thought) and then allowed students to work through how their Christian faith informs their response to this issue, then the students in this class would be given the opportunity to do exactly what Tisby urged.

But if I read the report rightly, this approach would not be allowed. [EDIT: After publication, I was encouraged to note that it was clarified on a Twitter thread by Grove City’s only Black faculty member that the whole Board has not yet adopted the report of its investigative committee, so there is still an opportunity for the Board to go another way.] The Board noted that to date it “has not promulgated a confessional statement to which all must subscribe” but also that it “categorically rejects Critical Race Theory and similar ‘critical’ schools of thought as antithetical to GCC’s mission and values.” As noted earlier, the Board did not define CRT, and hence the term stands in for approaches to race relations to their political left.

What is within the bounds of Christianity for faculty is not defined theologically, but politically. In other words, Grove City does not have a statement of faith, but it does now have a statement of politics.

This framing of the institution’s character necessarily limits the extent to which students are exposed to the diversity of voices that would help them work through the integration of their faith and their learning and their life, driven by the Scriptures and the historic creeds, rather than by American politicians.

The pressure at other Christian institutions could admittedly come from the other side of the political spectrum. The Bible contains claims that cut against both American political parties. In our hyper-polarized political climate, maintaining space for this exploration at private Christian colleges that rely on donors and enrollment to survive is legitimately difficult and will require creative and courageous leadership. Anxious Bench blogmeister Chris Gehrz recently wrote about one that seems to be succeeding. Christian higher education is a project I believe in, so here’s to hoping more Christian colleges and universities find a way to do so.