I have invented a new discipline, the Theology of Punctuation.

Some years ago, I published a book called Crucible of Faith: The Ancient Revolution That Made Our Modern Religious World, about the couple of centuries preceding Jesus’s time. One of the persistent problems I have relates to capitals and upper case letters. That may sound trivial, but it actually gets to some quite critical issues of translation and interpretation.

Let me take one famous quotation from the Gospels, concerning the birth of Christ. This is from Luke 2 (NIV), and I invite you to look at the punctuation, and the use of upper case letters:

But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

Nothing seems unusual or improper in that, and it seems natural and indeed essential to use capitals for a word like Savior. When we use capitals, we are making a clear statement about the words that we so dignify. We are stressing that those words represent something special, perhaps THE example of its kind, rather than any generic example. Jesus is to be a Savior, rather than just someone who saves something unspecified. In religion, we mean something totally different if we refer to Virgin rather than virgin, or if we refer to the Father and the Son, rather than the father and the son. To write of God is usually to refer to the one absolute and transcendent Creator (see, I capitalized that – did you notice?) while a god is a more commonplace thing. Often, our editorial decisions carry quite unintentional theological weight.

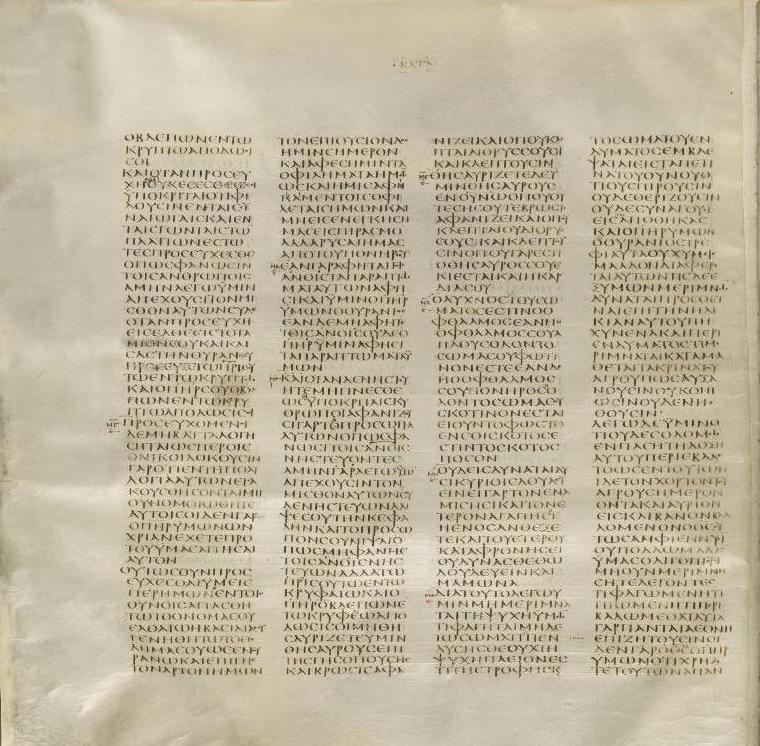

But here is the problem. Virtually all such decisions are arbitrary, and rely on editorial tradition. When we translate the New Testament, we have no capitals or upper/lower case differences to guide us. Very early Greek New Testament manuscripts are entirely in what we would call capitals or upper case. Hence, there is no distinction between upper and lower case, and thus (in our sense) no word is dignified or distinguished by a capital.

Matthew 6 in Codex Sinaiticus (Public Domain image)

When we read Peter’s confession of faith in Mark 8.29, he declares that “Su ei ho christos.” That can just as legitimately be translated in any of the following ways:

You are the Christ

You are the christ

You are the Messiah

You are the messiah

You are the Anointed

You are the anointed

You are the Anointed One

You are the anointed one.

All are correct, or at least defensible. You see what a difference capitals make? Not to mention the decision to translate a word in one particular form, rather than retaining its literal and original meaning.

Incidentally, my spellcheck tries to enforce theological correctness by insisting I capitalize Christ.

To go back to the angel’s words to the shepherds, the one born in the city of David is christos kurios, which could indeed be translated as “the Messiah, the Lord,” but other possibilities and punctuations are just as accurate. The KJV offers “a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.” “Anointed” and “anointed” are both valid options. Jerome’s Vulgate Latin offered Christus Dominus. If you wanted, you could also render good news as Good News.

You can think of so many other examples, but one of the weightiest (and best known) is the phrase translated as son of man (ho huios tou anthropou). In some instances in the Bible, that phrase indicates a generic human status. In others, it does imply some kind of messianic being. In translation, we indicate the difference as best we understand it by capitals (Son of Man) and hope fervently that we are interpreting correctly. But as I say, the languages of the original texts offer not the slightest clue about capitalization.

In no particular order, I offer some other examples where our capitalization policy can make a vast difference in reading and interpreting a passage:

End of the Age, and end of the age.

Wisdom, and wisdom.

Devil, and devil.

Satan, and satan.

Lamb, and lamb.

Lord, and lord.

Scripture, and scripture.

Father and Son, and father and son.

World, and world.

The Holy One of God, and the holy one of God.

Son of God, and son of God.

But let me repeat that basic and oft-forgotten rule. The capitals in the scriptures we read today are put there by translators, and might or might not reflect the meaning or intention of the original writers. However objectively and intelligently they are doing their job, the theology we read into those capitals is the work of those translators.

On a closely related topic, I have also discussed the “Curse of Quotation Marks” in Bible translations.