Scholars have long described the global ambitions of White Protestant American as rooted in a sense of exceptionalism animated by notions of racial and religious ascendancy. But as Stanford historian Kathryn Gin Lum argues, we cannot limit our attention to understanding how “a White American Christian superiority complex” has driven Americans to see themselves as set apart and called to be saviors of the world. We also need to understand how they viewed the people whom they endeavored to save and transform–in other words, the “heathens” of the world.

Scholars have long described the global ambitions of White Protestant American as rooted in a sense of exceptionalism animated by notions of racial and religious ascendancy. But as Stanford historian Kathryn Gin Lum argues, we cannot limit our attention to understanding how “a White American Christian superiority complex” has driven Americans to see themselves as set apart and called to be saviors of the world. We also need to understand how they viewed the people whom they endeavored to save and transform–in other words, the “heathens” of the world.

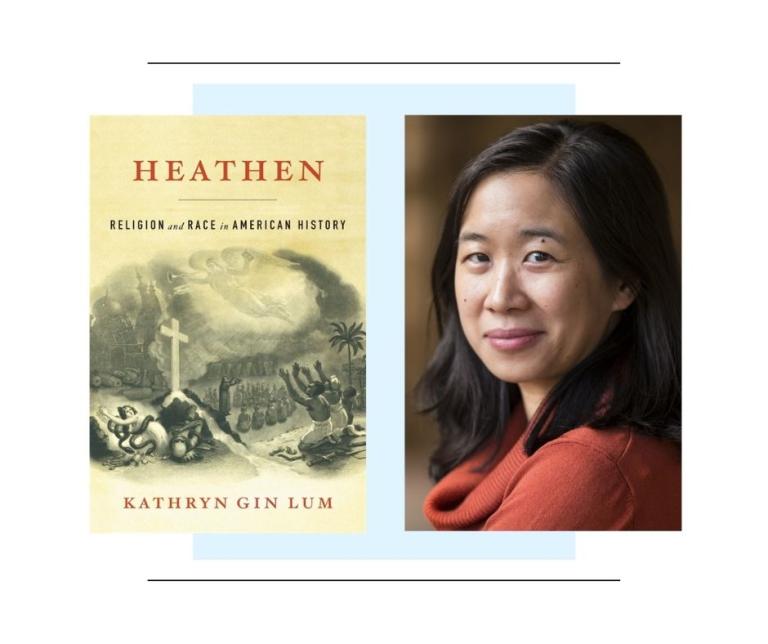

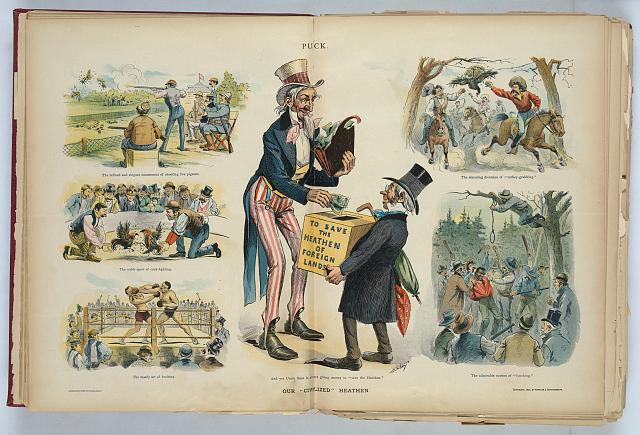

This topic is the subject of Gin Lum’s new book, Heathen: Religion and Race in American History, published by Harvard University Press later this month. In Heathen, Gin Lum builds on some of the ideas she presented in her first book, Damned Nation: Hell in America from the Revolution to Reconstruction (Oxford University Press), a history of ideas of damnation. This time, though, she focuses not on hell, but on the people believed to be destined for it. In so doing, she tells a much larger story about the durability of cultural categories, the meaning of history, and the emergence of ideas of about racial difference, which she sees as intertwined with religious difference. As Gin Lum persuasively and provocatively argues in this book, “racial othering has been a ‘heathen inheritance.'”

I had the good fortune of discussing Heathen with Gin Lum last month. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Melissa Borja: What is the story behind your book?

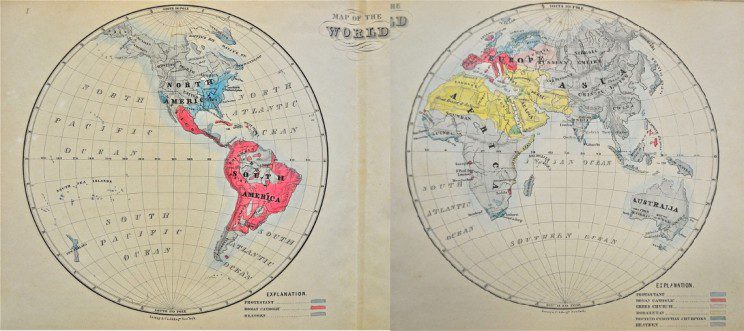

Kathryn Gin Lum: There are really two stories behind the book, one academic and one personal. On the academic side, this book started back when I was a senior writing a thesis on missions in Gold Rush-era California. I was interested in Protestant missionaries and how they interacted with the Euro-American and the Chinese populations in California. I was especially interested in how they would sometimes refer to Chinese Christians as ‘heathen converts,’ and to Euro-Americans as ‘dead Christians’ when they acted in ways that Protestants did not consider to be ‘Christian.’ At the same time, I came across a mid-19th century missionary map of the world color-coded by religion, that showed the vast majority of the world as gray, for ‘heathen.’ This all got me to wonder: what does the figure of the ‘heathen’ entail? How can this category be so all-encompassing, and persist for some groups of people even after they convert? And what does this way of looking at the world tell us about the racial imagination of 19th-century white American Protestants?

I took a slight detour to the idea of hell for my first book, but really, that’s also related to this project because the heathen are understood to be damned if they don’t convert. If you look at a missionary map like this, what you’re really looking at is how much of the world white American Protestants believed were going to hell if they didn’t save them. The first book had more of a national focus and was more bounded in terms of time. In the second book, I try to take a much more sweeping view of the history of this concept of the heathen.

In terms of the personal story behind the book, I was raised in a conservative Christian denomination. I grew up thinking that there were heathens in the world and that it was my responsibility to help save them. And because I’m also Chinese American, I grew up wondering about my ancestors in China, about relatives that I never knew. I grew up worrying about them and wondering if they were going to hell.

I write in the book that childhood me could really be a primary source for historian me. And then I say that, actually, me right now could continue to be a primary source for historian me because I continue to think about these issues and about the faith-based implications of the questions that I ask from an academic perspective.

MB: Can you tell us what the main argument is of your book? I know it’s very complex. Walk us through some of the arguments.

KGL: So the central question I’m asking in the book is how the ‘heathen’ as a religious category of difference relates to racial othering. In George Fredrickson’s classic, Racism: A Short History, he writes about the ‘heathen’ as a religious category that is not yet racial, and the reason that he gives for this is because the heathen is thought to be changeable. The heathen can be converted out of heathenism. For Fredrickson, and for a number of other scholars, race has to incorporate an idea of innate, inherent difference, rooted in the body and not in belief. Race arises later, and it comes to replace religion as the primary way of differentiating between people. In the book, I call this the ‘replacement narrative.’

But what I try to argue is that the religious category of the heathen is not replaced by racial categories. The figure of the heathen continues to inform, and even underlie, race-making and racism in the U.S. There are, of course, many ways to think about race and racism. One way is as a socially constructed, hierarchical system of discrimination based on perceived differences between people that are understood to be inherent and unchangeable. That way aligns with Fredrickson’s view of race. But race doesn’t only operate in hierarchical gradations based on perceived phenotypical differences. It can also work in a kind of blunt binary: the binary us versus them, of white people versus everyone else. And here, I think, is where the category of the heathen–a broad umbrella that sweeps together so many different parts of the world–is still so powerful and still informs how white Americans look at the world.

It traces back to that missionary map again: Where do we get this way of viewing the world where people from vastly different areas and vastly different regions are lumped together under broad headings like the ‘Third World’ or ‘developing nations’? I argue that it comes from the idea of the ‘heathen world’ and this ongoing conception of the ‘heathen’ who needs help.

In making this argument, I am drawing from Sylvester Johnson’s book, African American Religions, 1500-2000: Colonialism, Democracy, and Freedom. Johnson writes about race as colonial governance, as the differentiation between the European and the non-European, between those who designate themselves as ‘governors’ and those they designate as the ‘governed.’ That’s really what’s at play in how I’m thinking about the ‘heathen’ as a religious and racial category. Designating people as ‘heathen’ implies that their lands and lives need to be changed, rooted as they are in supposedly ‘wrong’ belief. So I’m really trying to complicate what Fredrickson says about race, and to show how the quality of changeability is actually key to the way that racialization works in and as colonial governance.

MB: I’m really compelled by this description of how ideas about religion inform ideas about race. Could you give a good example to illustrate how those two categories are operating together?

KGL: Oh, there are so many examples. In the book I call heathenism a ‘get out of jail free’ ticket that’s used to rationalize all manner of atrocities in the name of saving the ‘heathen.’ It’s used as an excuse to justify enslavement. It’s used as an excuse for the creation of residential schools, and even today it’s been appallingly used to justify the hundreds of Indigenous childrens’ graves that have been found at those schools. It’s used as a reason to annex Hawai‘i. And you could say for all of these examples that, well, the ‘heathen’ ticket is just an excuse, and fundamentally all of these examples are about the desire for capital, labor, and land. Absolutely, that desire is central. But that doesn’t make the justifications unimportant. I don’t think that we can or should dismiss the significance of the ‘heathen’ ticket that is used again and again, to this day, to make greed look good. Of course, some–even many–people have believed that they really have been doing good in bringing ‘help’ to the ‘heathen,’ whatever the costs, but one of the things that I hope my book does is to encourage readers to look at the implications of such motivations.

MB: Yes. I think what’s so powerful about what you’re describing is how adaptable and useful the category has been to reproduce unequal relations of power.

KGL: Right.

MB: There are a lot of different ways that your book connects to the scholarship on religion, on empire, on race. Could you outline some of the main interventions that your book makes, both in the scholarship and in how the broader public thinks about religion and race and history?

KGL: I’ve spent a bit of time on religion and race already, so let me focus on history here, though of course they’re all related. One of the central things that made people ‘heathen’ was supposed to be their lack of historical development. Some so-called heathens were thought to be in the childhood of human history, so basically historyless. Others were thought to have stagnated; to have hit a kind of ‘heathen ceiling’ beyond which they could no longer develop until and unless they converted.

I argue in the book that the category of ‘heathen’ is really useful for Americans who are anxious about their own, very young, experimental nation. When they compare themselves to China, for instance, some worry arises since China seems so ancient, with such a long-lasting ‘civilization.’ But here’s the thing–if China has hit the ‘heathen ceiling,’ then Americans believe that it can’t develop any further until the entire nation is brought to Christianity. That’s because, as heathens, the Chinese are supposed to have misunderstood the nature of the land and their relationship to it. They worship ancestors and spirits in the land (‘feng shui superstitions,’ as white Americans liked to say), and so they don’t want to disturb the ancestors’ bones, carve the land up, put it to use. They’ll do that as laborers in America, but not in China.

By contrast, even if America is a much younger nation, Americans reassure themselves that they’re on a much steeper trajectory of development. White Americans in the nineteenth century pride themselves on developing all these machines to make the land productive, on charging forward through history, while ‘heathens’ are basically stuck in time because of their misguided beliefs.

This is the backdrop to the professionalization of history as a modern academic discipline in the United States. I recently learned that the American Historical Association was organized in 1884, two years after passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. I think it’s no accident that assumptions about ‘authentic history’ drew from ideas then-circulating about progress-driven Christians in contrast to stagnating pagans.

And I think that they continue to inform the discipline. History is supposed to change over time. That’s what I was taught as a historian-in-training. But that’s a progress-driven way of thinking about history, and we need to also think about history as cyclical, as repetitive, as continuous. I worked through some of these ideas in an earlier article, and this book is my attempt to write a history that does what the article calls for. I try to show the repetitiveness of how the category of ‘heathen’ has been used, again and again, by the very people who think they are changing over time, charging forward through time.

Another intervention the book tries to make is at an ethical level of thinking about how Americans interact with and think about the world. This is a complicated history of people who are trying to do things that they think or claim are beneficial for others and in some cases really are or could be understood to be, like clean water initiatives. There’s all sorts of initiatives that grow out of the impulse to help other people. As an aside, there’s a little part of the book where I talk about the Silicon Valley and the tech impulse to save the world. Being in the Silicon Valley, I’m very steeped in techno-salvation language, and I see that also as a continuity of these 19th century discourses.

But for Americans to define themselves as helpers defines others as helpless/needy. It creates a binary that is both religious and racial, between an ever-changing, progressive ‘us,’ and a stagnant but changeable ‘them.’ So how does it shape how Americans think about themselves and their actions in the world to see how these kinds of discourses continue to this day?

MB: I wonder if you could give specific examples of how you’re seeing this heathen logic at work today–perhaps in this new cycle of tensions between the US and China, for example, or in relation to the relationship between the US and the rest of the world. How are you seeing ideas about the heathen deployed in our current moment, and what work is it doing in the current moment?

KGL: I started writing this book well before COVID, but I finished drafting it at the beginning of the pandemic, when it felt like both everything and nothing had changed. I ended up adding a postscript on COVID, which I first drafted in the spring of 2020, when Trump was trying to deflect all blame to China for COVID. In his language and in the media, I saw the same ideas that had been used to denigrate the Chinese as ‘heathen’ in the 19th century: ideas about unsanitary eating habits, weird beliefs, wet markets, ‘magic,’ all of which supposedly lead to disease and contagion.

But then at the same time, there was really interesting pushback against this narrative.

People have been able to use the category of the ‘heathen’ over time as a really powerful way to critique white Americans. Another metaphor that comes up in the book is the ‘heathen barometer,’ a way to detect ‘heathenish’ behaviors among white Americans and to call out white Americans for acting like the heathens they’re supposedly trying to save.

We don’t use the word ‘heathen’ anymore, for the most part, but we do use replacements for it, like ‘third world’ and ‘developing country.’ So, at the beginning of the pandemic, when the country just seemed to be completely failing at how to meet this challenge, people were comparing the United States to a third world country. Nurses and doctors were saying, ‘I cannot believe we are being forced to wear garbage bags because we don’t have enough PPE.’ Articles were coming out in the news on how America was turning to China for sanitizer and masks because we couldn’t produce them quickly enough. And I remember someone said on Twitter that ‘The United States is a Third World country in a Gucci belt.’ So this is an example of the heathen barometer in action, or I guess you could call it a ‘third world barometer,’ to say: you are not being who you claim you are or who you’re dressed up as. You are actually being who you claim you’re helping. But you’re the one who really needs help.

With the recent crisis in Ukraine, I’m seeing a lot of resonances there as well, particularly in how the media has covered the war and the kind of shock that they’ve expressed over war in Europe, in supposedly ‘civilized’ countries. The whole category of the ‘civilized’ country versus the countries where violence is expected traces back again to the binary, broad strokes, Christian versus ‘heathen’ dynamic.

MB: To sum up all of these things you’re discussing about heathenness: even though we don’t use the word heathen, that logic is still operating, but it goes by different names.

KGL: Yes. It’s in some ways so obvious once you see it. But the work that I’m trying to do is to tease out and understand how these heathen metaphors or logics–the umbrella, the get out of jail free ticket, the ceiling, the barometer–iterate and reiterate over time.