“Have you been to St. Thomas yet?”

“Have you been to St. Thomas yet?”

The question buzzed my phone. It was from one of my former students who knew I was in Salisbury. What she didn’t know was that, when I read her text, the Salisbury Cathedral spire soared above me as I sat below the glass ceiling of the refectory cafe drinking tea. In two hours I would meet the archivist to view the only copy of a Middle English sermon collection housed in the cathedral library. Until then, I had time to kill.

So I went, after finishing my tea. I walked the short distance from the cathedral to the parish church of St. Thomas and St. Edmunds. It is the oldest building in Salisbury, built in the early thirteenth-century as the town shifted two miles from the cathedral and castle at Old Sarum to the location of the current cathedral.

The chuch took my breath away.

As it stands today, St. Thomas is a far cry from the “gloomy” church Thomas Hardy described in Jude the Obscure. Dominating the nave above the chancel arch is the largest and best preserved “Doom” painting from medieval England. Originally created around 1470, it was whitewashed in 1593 and not seen again until the nineteenth-century. Today  the vibrant scene gleams in medieval glory, thanks to a very recent restoration project. “Doom” is an old English word for judgement, which is exactly what the painting represents: the Last Judgement as described in Matthew 25:31-46. The resurrected Christ sits on a rainbow presiding over the condemenation of the damned and the salvation of the blessed. Local lore whispers that one of the tortured souls belongs to Agnes Bottenham. Apparently founding the Trinity Hospital for the Poor in the late fourteenth century (today Salisbury Almshouses) wasn’t penance enough for running a brothel. If Agnes is among the damned, she is in good company. Both a bishop and royalty join her. “Nulla est Redemptio,” wrote the artist: “There is no escape for the wicked.” Meanwhile her more righteous neighbors follow angels into the bliss of heaven.

the vibrant scene gleams in medieval glory, thanks to a very recent restoration project. “Doom” is an old English word for judgement, which is exactly what the painting represents: the Last Judgement as described in Matthew 25:31-46. The resurrected Christ sits on a rainbow presiding over the condemenation of the damned and the salvation of the blessed. Local lore whispers that one of the tortured souls belongs to Agnes Bottenham. Apparently founding the Trinity Hospital for the Poor in the late fourteenth century (today Salisbury Almshouses) wasn’t penance enough for running a brothel. If Agnes is among the damned, she is in good company. Both a bishop and royalty join her. “Nulla est Redemptio,” wrote the artist: “There is no escape for the wicked.” Meanwhile her more righteous neighbors follow angels into the bliss of heaven.

It is an incredible painting. But it isn’t what stopped me in my tracks. Three more fifteenth-century paintings survive in the Lady Chapel of the church of St. Thomas, depicting three scenes from the life of Mary the mother of Jesus: the nativity, the visit with Elizabeth, and the annunciation.

One of the most frequent questions I receive from folk reading The Making of Biblical Womanhood (after which Bible translation do I recommend) is about the Reformation. Was it good or bad for women, they ask. My response usually isn’t what folk want to hear. It is neither, I say. It isn’t that the medieval world was a golden age for female authority (because it wasn’t); it isn’t that elevating the position of wives during the Reformation era was wrong or harmful for all women (because it wasn’t); it isn’t even that patriarchy was less present in the medieval world than in the early modern world (remember Judith Bennett’s patriarchal equilibrium?). It is simply that ideas about women and the circumstances of women’s lives shifted across the Reformation era, and these shifts made an already difficult situation for women in ministry (as preachers, teachers, leaders, etc.) more difficult.

Let me give you a concrete example of how ideas about women shifted across the Reformation era–and it is an example connected to the annunciation painting in the Lady Chapel of St. Thomas. Just look at the painting (image below). If you are from an evangelical/low-church tradition, do you see something that surprises you?

The angel delivering the news that Mary will give birth to the savior of the world interrupts her reading a book (probably either Psalms or Isaiah). This depiction of Mary reading was a regular feature in medieval depictions of the annunciation. Y’all, this isn’t a teenage girl who “didn’t know” the scriptures prophecying the Messiah. It is an educated woman who reads scripture unmediated. Her “interpretative, revelatory power enabled by her reading” (265) served as a medieval exemplar of female teaching authority that was modeled by other women and even accepted by men.

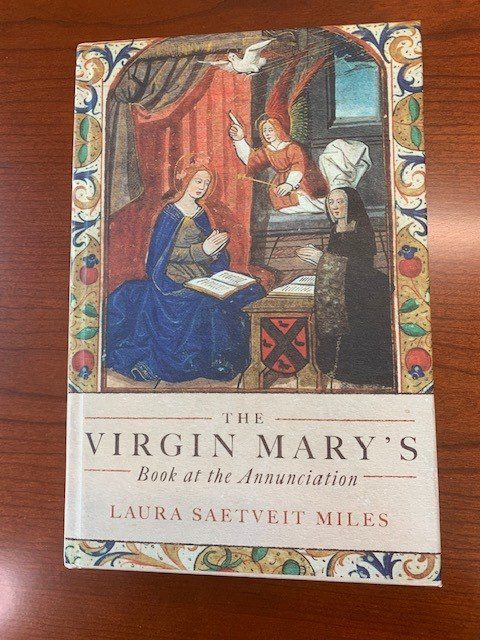

Don’t believe me? Well, I have a book for you that is releasing this month in paperback: Laura Saetveit Miles’ The Virgin Mary’s Book at the Annunciation.

Don’t believe me? Well, I have a book for you that is releasing this month in paperback: Laura Saetveit Miles’ The Virgin Mary’s Book at the Annunciation.

I don’t usually shout when I read medieval scholarship. But I did when I finished this book (just ask my husband–he was in the car with me). As I summarized recently for an article, Miles shows that the image of Mary, the mother of God, as a pious reader of scripture was just as relatable to medieval Christians as to Protestant reformers. “Mary as accessible to the godly layperson might ring true in the Protestant world,” concedes Miles. Yet, “an accessible Mary also rang true in the Catholic pre-Reformation world.” Even as Mary was “simultaneously the most elevated of women, the Queen of Heaven and the mediatrix to the Saviour,” writes Miles, “she was also a woman who liked to sit and read and pray, a way of being that medieval women found accessible and relevant” (256-257).

Most significantly, Mary sitting and reading in the medieval world was not an image of quiet domesticity. It was a powerful image that helped legitimize women’s authority unmediated by male oversight. As Miles explains, Mary wasn’t “alone of all her sex” (as she has been famously described) because medieval women were meant to emulate her female authority. “Before the male body of Christ becomes visible,” Miles writes, “it is Mary’s body that brings together these holy women across time and space at her side in her solitary room. It is her channeling of the Word that legitimates their written words, rendering superfluous male authorities–at least in the sacred visionary sphere” (174). Mary’s example inspired medieval women to exercise religious authority. Instead of a “source of subjection and silencing for medieval women” (119), the reading Mary empowered medieval women like Elizabeth of Hungary, Birgitta of Sweden, Julian of Norwich, and even Margery Kempe.

It is true that the post-Reformation world continued to depict Mary as pious reader. Yet, because they did so “unaware of the powerful affective devotional tradition surrounding the motif in the Middle Ages,” the post-Reformation reading Mary was diminished. No longer a visionary prophet and intercessor who drew authority from her own reading (the medieval Mary didn’t need a man for spiritual covering), Mary’s reading at the annunciation was instead interpreted through the lens of Protestantism: a devout and literate laywoman quietly reading in her home.

So how did the Reformation matter for women?

I’ll let you read Laura Saetveit Miles’ brilliant book and think about it.