Worship wars. The phrase might bring to mind debates about contemporary or traditional music, or about how to incorporate liturgy into services, or even about whether drum sets are appropriate in worship. But for an early modern audience, worship wars might have been literal physical altercations. Some well-known conflicts, like Zwingli’s Affair of the Sausages or Karlstadt’s debate with Luther over the mass, involved debates about theological sacramental principles that led to arrests and exiles. Other conflicts, though, turned far more violent, as large groups of lay people protested liturgical changes and government attempts to enforce their authority over how churches worshipped. Two lesser-known conflicts– one from England and one from Sweden– help us see some common themes and contexts in these early modern worship wars.

The Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549: An English “Worship War”

One of these “worship wars” is described in Chapter 6 of Eamon Duffy’s The Voices of Morebath, a book I teach each spring which follows the course of the English Reformations in the small village of Morebath in southwestern England. Known as the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, the conflict actually stretched from 1547 (where it started with the mob killing of an ironically named archdeacon, William Body) until the execution of some of the surviving rebels in January of 1550.

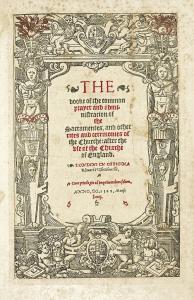

The tensions in 1547 were not necessarily new ones: the waves of religious reform associated with the English Reformations, starting with Henry VIII and now proceeding from his heir, the new king Edward VI, had always caused tension and dissent in their application, particularly as familiar rhythms, words, and customs of worship and parish ritual were reformed or eliminated. In the context of the English crown’s dissolution of the monasteries in the preceding decade, concerns about state seizure of the property of the parish ran high. So when the 1549 Act of Uniformity outlawed the traditional Latin liturgical rites and mandated that a new service be used, the parishioners of Devon and Cornwall felt that things had gone too far. The new rites in English felt like yet another attempt to erase local identity and custom; coupled with new taxes and the confiscation of communal property, the mandated change in worship was the final straw for the parishioners of the region.

Parishes throughout Cornwall and Devon broke into open rebellion: parishioners started by forcing their priests to perform the old rites, then massed as an army of as many as 16,000 people to besiege Exeter, take back their confiscated parish property, and protect their traditions against the expansion of the gentry. Despite holding their own in a series of battles and imprisoning a number of the local gentry, ultimately, the uprising failed. Over 5,500 people died during the rebellion, with executions after its suppression of those suspected of leading or inciting it, including mayors and priests. The English prayer book prevailed, at least until Mary took the throne.

The Dackefejden of 1542: A Swedish “Worship War”

It’s not just in England that we see literal worship wars over prayer books, however. Around the same time period, in Sweden in the 1540s, another “worship war” took place, with similar protests over royal changes to religious practice and liturgies, as noted by Tobias E. Hämmerle in a brief article about the Dackefejden’s religious causes. Gustav Vasa had taken power as the king of Sweden in 1523, breaking Sweden away from Denmark and establishing Protestantism as the national religion. As he established his political and religious authority, Vasa made several changes: he banned trade with Denmark to help establish Swedish sovereignty, he introduced new taxes that came directly to the king rather than to local lords, he confiscated church properties and valuables, and he pushed through the introduction of a new mass book and manual for religious instruction. These last two changes- the introduction of a new mass book and religious instruction- were the final straw for Nils Dacke, a peasant from the border region of Småland.

After a visit from the king’s archbishop, which enforced both the new mass book and the new taxes, Dacke led a group of several thousand peasants (estimates vary between 3,000 and 20,000) in a revolt against Vasa. The uprising started in June 1542, as Dacke and his followers assassinated the king’s sheriffs and tax collectors. After seizing control of much of southern Sweden and defeating the German mercenaries Vasa sent in to quell the rebellion, Vasa was forced to sign a ceasefire, and Dacke became the de facto ruler of Småland and much of southern Sweden. He reinstated Catholic masses, reopened the border trade between Sweden and Denmark, and abolished the hated royal taxes. Dacke and his peasants returned the region to its traditional local dynamics, in which peasants negotiated with local lords and church authorities in a form of collaborative government. In January 1543, however, Vasa broke the ceasefire, sending in a much larger and better trained army and forcing Dacke and his army into a pitched battle on an icy lake. This was the beginning of the end for the peasants, who were then hunted down and executed, with Dacke dying (and then posthumously executed as a traitor) in the summer of 1543. So ended the Dackefejden, with the deaths of the peasants, the reestablishment of the Swedish state church mass, and the reinstitution of the new tax system.

Causes, Causalities, and Considerations for Today

It’s certainly a bit simplistic to call these early modern conflicts “worship wars,” as the economic and political debates surrounding these episodes make clear. Although liturgy, prayer books, and worship were the final tipping points for both groups of early modern peasants, government attempts to confiscate church property or to consolidate power over these border regions played a part as well. There is clearly a story to tell here about the ways in which wealth creates complications and power struggles, particularly when one group tries to take it from another. There’s also clearly a story here about the ways in which the intersection of nationalism and faith can be deadly, particularly when one vision of faith is closely knit to one vision of national identity.

I think it’s important not to overlook the aspects of these conflicts that center on worship and liturgy, though. While economic, political, and social tensions clearly exacerbated these conflicts, in both England and Sweden, worship and liturgy played a huge part in pushing these groups of lay people into active rebellion. Clearly, our modern era is not the first time that strongly held feelings over traditional versus contemporary worship led to church splits! It’s worth noting just who the casualties are in these early modern splits (and perhaps in our own): those with the least amount of voice, say, and input. The groups most harmed by these early modern conflicts (and, I think, in our own fights) are those who are marginalized in earthly structures and yet committed to their faiths, with clear convictions as to how to worship rightly. As we think about these early modern episodes, I think it’s worth reevaluating our own “worship wars” with a focus not just on theological conviction about things like liturgy or leadership, but also on the cost of reforming or not reforming. Who might be caught in the crossfire of the conversation, to the detriment of the well-being of their faith?