I posted about my current book project, Storm of Images, which concerns the Iconoclasm struggle in the Byzantine Empire between about 720 and 850. I argue that this was an extraordinarily important moment in the history of Christianity, with enduring consequences for both east and west. The Council that marks the success of the pro-image cause, the Second Council of Nicea in 787, was the last General Council that is still regarded as valid by both East and West, Catholic and Orthodox, and many Protestants. It is mysterious then that the whole affair is not better known by non-specialists, and few are aware of the amazing body of scholarship that has become available in recent decades.

Partly, I think this is because we often assume that this was exclusively a matter of the eastern churches. Westerners, we think, don’t even have icons, so who cares about Iconoclasm? In reality, eikon refers to all images and depictions of sacred figures and in any media, not just icons properly defined. But “Byzantine” also poses problems. Note the quotes around Byzantine, an unsatisfactory term that really serves to marginalize this crucially important episode in the wider Christian world.

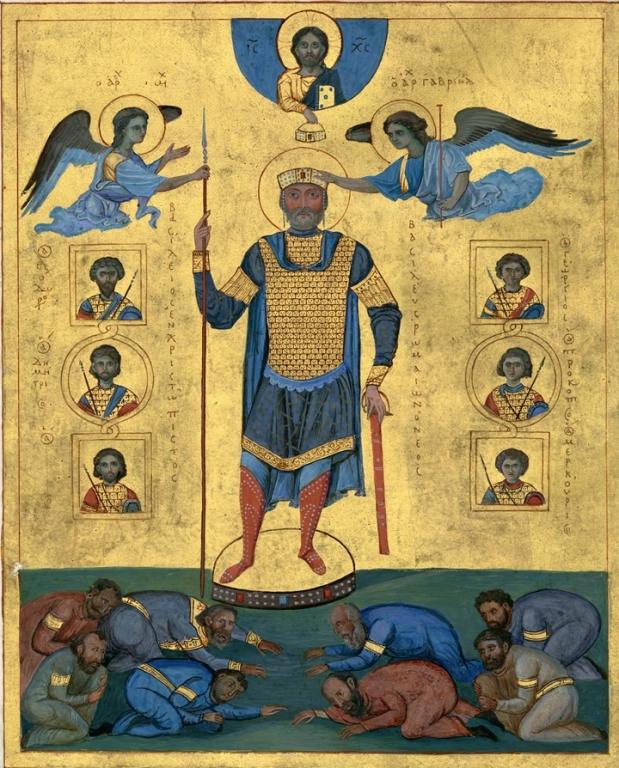

I have a long-standing fascination with that Byzantine world. When I was about eleven, I came across a library book that mentioned how the sack of the city of Rome in the fifth century (actually, two sacks, in 410 and 455) had in no sense ended the larger Roman Empire, which persisted in Constantinople until 1453. I found this idea quite wonderful. I had visions, highly inaccurate ones, of Romans with togas sitting in amphitheaters a thousand years out of their time. If I have since lost the togas, I have never abandoned my interest in that glamorous eastern world, which was for so long the world’s most powerful Christian entity, and the cultural, spiritual, and intellectual heart of the Christian world. I have posted at this site in years gone by about making the pilgrimage to Ravenna, with its astounding Byzantine art-works.

But as I have said, that Byzantine term is problematic. Referring to the empire of the eighth and ninth centuries, the word is a perfectly correct usage. Having said that, it has somewhat disreputable connotations in English, suggesting as it does over-elaborate or needlessly complicated, over-bureaucratic, not to mention hinting at plots and conspiracies. It suggests almost a willful remoteness or obscurity, a historical byway, not unlike “Ruritanian.”

Also, to speak of “Byzantine” undermines the very substantial continuities from the Later Roman Empire. “Byzantine” people in 700 or 800 called themselves Roman, lived in the Roman Empire, and spoke the Roman tongue, which was Greek. Writers sometimes described their realm as “Romania.” When the remnants of the empire fell to the Ottomans in 1453, the new Islamic Ottoman ruler, Mehmed, claimed the title of Qayser-i Rûm, Emperor of Rome. The conquered Greek Christians became known as the Roman millet or nation. Only in the sixteenth century did West European historians popularize the term “Byzantine Empire”. Generally, throughout my present book, I speak of the Roman Empire, rather than the Byzantine.

To speak of “Byzantine,” then, consigns the subject to near-irrelevance for most non-specialists. But in this instance more than most, this usage really matters, as the image struggle was assuredly not confined to such a forgotten entity. It was a debate that affected much of the Near East and the Mediterranean world, and its implications affected large sections of Europe. Much of the “Byzantine” debate over images involved the right of a church in one particular region to make significant decisions about faith or doctrine without the knowledge or consent of the wider Christian world. The image struggle was of its nature a universal or ecumenical matter, a transnational encounter that spanned the still expansive Christian territories of Late Antiquity.

The struggle was no more “Byzantine” than was, say, the Council of Chalcedon of 451, which actually did take place in a city within the metropolitan orbit of the city of Byzantion, that is, Constantinople. The city of Nicea is not much further removed, and to that extent, is just as “Byzantine.” Yet the Second Council of Nicea, like the First, was a moment in Roman Christian history, and, like its predecessor, it was of profound concern to all Christendom, for Rome or Antioch as much as Constantinople.

Moreover, image conflict went far beyond the “Byzantine” state. This was a pivotal moment in shaping the beliefs and customs of the Eastern and Orthodox churches, which looked to the Second Council of Nicea as a critical affirmation of Christian belief, almost as vital as its more famous predecessor had been, back in 325. The eastern Roman world that emerged from the image struggle was the source of Christian conversion of eastern Europe, including Russia. Still at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Orthodox churches accounted for almost a third of all Christian believers, and they cherished their icons.

So yes, this did matter enormously for Christian history, worldwide.