I firmly believe that the climate is changing, the world is warming in response to human actions, and that these developments are deeply alarming for our collective long-term planetary future. I also believe we need to be very careful about how we seek to use current events to prove those facts, and to argue for policies. In the worst case scenario, deploying such events in a misleading or tendentious way risks discrediting the case we are seeking to make.

Britain recently had an extreme if short lived heat wave, when the temperature briefly touched the magic forty degrees – that is of course Celsius, which is 104 Fahrenheit, or what we in Texas call “starting to get warm.” Seriously, large parts of the US are suffering a vicious heat wave, and we all remember the terrifying forest fires that have ravaged Northern California in recent years. Very often, these instances are presented to support the case of “NOW, do you believe in climate change? What are you going to do about it?” To take one example out of a great many, I quote the Economist:

There comes a moment when the penny drops. And in Britain this week the sound of dropping pennies was loud. Though Britons are by no means the worst affected by the heatwaves now sweeping the northern hemisphere, they have been in awe of a particular round number: 40°C. This is an air temperature never before recorded in the United Kingdom. But it was matched and exceeded in several places on July 19th. It is one thing to understand intellectually that anthropogenic [human-driven] global warming is real, quite another to feel one’s own brain baking.

Or here is Margaret Renkl in the New York Times,

Regardless of how they vote, most people — even the most ideologically invested — don’t discount their own senses. They can feel the effects of this summer’s heat wave. They can see the lakes drying up and the trees dying. They can smell the smoke of wildfires. They can hear the hurricane’s roar. They may prefer a term like “extreme weather” over a term like “climate change,” but they understand what’s going on.

Here is the problem. Of themselves, these various outbreaks might or might not confirm global warming, but they do not necessarily substantiate the long term trends arising from anthropogenic climate change, via emissions from fossil fuels. Whatever Ms Renkl implies, “extreme weather” might or might not be connected to “climate change,” or in the larger sense, to “what is going on.” This is not just a quibble over terminology, and “extreme weather” is not a polite euphemism. You can have really lethally extreme weather quite independent of a larger climate change context.

A historical perspective is crucial. If you say, for instance, that X was the worst natural disaster of its kind for a century, or two centuries, then what you are also saying is that in fact, the same or worse happened a century or two back, when emissions were nothing like the same problem they are now. Therefore our present situation is not unprecedented, and that earlier disaster might or not have any relationship to carbon emissions. However bad Europe’s heatwaves and droughts might be this year, they are not going to be close to conditions in the horror year of 1540. If you say that the US southwest is currently suffering the worst megadrought in 1,200 years, which it is, then you are admitting that that region was just as hot and dry in the ninth century as it is today. If those ninth century circumstances passed in time, that invites the question of why we should not just try to wait out our present problems and challenges?

Do Californian forest fires prove climate change? Again, maybe or maybe not, but their impact is vastly aggravated by decades of scandalously bad forest management practices.

I offer a case in point. Responding to those current events in Britain, conservative journalist Michael Deacon published a column entitled “Ignore the heatwave hysteria. The Edwardians had it just as bad,” and as he said, “Long before mass-produced cars, commercial flights and climate activism, Britain survived a summer of ferocious heat,” specifically in 1911: “In the summer of 1911 – long before cars filled the roads and planes filled the skies – Britain endured a heatwave that was only slightly less hot than this week’s, with temperatures reaching 98.1F (36.7C). The main difference is that it lasted far longer. Rather than two days, it lasted two months.”

So was Deacon making things up, or exaggerating? Not in the slightest. He is dead right. 1911 was marked by a devastating heat wave in Western Europe and North America, which among other things gave Boston its all time high, of around 104. Hundreds died in the US alone.

I mentioned Texas. That state is currently in the midst of a critical drought, in what is projected to be one if its driest years ever. 2018 was about as bad. So there we have clear evidence of extreme weather and current climate change, right? But in terms of precipitation, these current crises look very much like the legendarily dry Texan years of 1954 and 1956. Those were part of the historic drought of 1949-1957 portrayed by Elmer Kelton in The Time It Never Rained (1973), one of the finest pieces of American fiction inspired by climate. Those four years – 1954, 1956, 2018, and 2022 – stand among the worst five recorded in Texas history, but none comes vaguely close to the cataclysmic drought of 1925, a dreadful blow that struck across much of the American South, and which set the stage for the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. The years 1917-1918 weren’t much better, in Texas or nationally. Things could, and can, be very bad indeed without necessarily being tied to human-driven climate change.

What we make of all this is open to discussion. A climate skeptic could say that we have had conditions like those of the present day before, now we have them again, and it is all part of the circle of life. Hence, global climate change is a myth. Did we not have a Medieval Warm Period? And yes, you bet, we did, although we can argue about its geographical scope. Our planet is a very complex and dynamic system that we are only beginning to understand.

Or we could answer as I do which is that yes, we had catastrophic weather in past eras, arising from a variety of factors and reasons, including the levels of energy released by the sun, oceanic cycles (El Niño, the North Atlantic Oscillation, and others), or the impact of volcanoes. But these were all transient. What is totally different today is that the changes we are seeing in climate presently mark a permanent one-directional change and will not just go away of their own accord. This really is the new normal. That is a fundamental reality with which all future policymakers will have to deal. It will also cause a basic rethinking of most of our religious assumptions.

That is what I believe, and that reflects a pretty fair scientific consensus about “what is going on.” But it would be foolish to try and prove that case by drawing on odd and sporadic weather disasters which might arise from lots of miscellaneous factors, and assuming that they must be part of systematic global warming. Because if you do, some bad person – let’s call them what they are, “historians” – is going to produce annoying facts that show why what you are saying is so misleading.They will point you to horrendous episodes of flooding or heatwaves or megadroughts or other catastrophes that occurred in the dim and distant past, long before they could plausibly be associated with those surging fossil fuel emissions. Just to take a US example, an event like Hurricane Agnes (1972) set a very high bar by which to judge any more recent climate assaults.

Let’s not use every odd disaster and black swan event that we read about in today’s headlines as if they somehow portend the future. And let’s be especially cautious about that loaded word “unprecedented.” Or to shift the animal analogy from swans: let’s not cry wolf. The climate wolf really will be here soon enough.

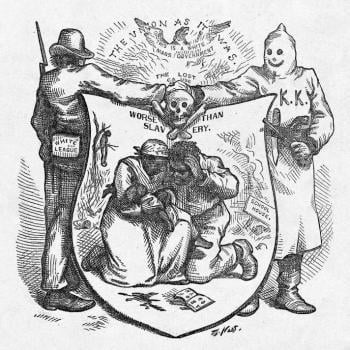

Meanwhile, let’s welcome all the tough questions from climate skeptics and “denialists,” who help keep the debate honest.