I’m so pleased to welcome Katherine Goodwin back to The Anxious Bench. Katherine is. PhD candidate in the Baylor History department studying religion and culture in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Last spring she had the opportunity to teach for a semester in Maastricht with a Baylor abroad program and today she shares about a memorable side trip into the forgotten history of medieval beguines.

I’m so pleased to welcome Katherine Goodwin back to The Anxious Bench. Katherine is. PhD candidate in the Baylor History department studying religion and culture in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Last spring she had the opportunity to teach for a semester in Maastricht with a Baylor abroad program and today she shares about a memorable side trip into the forgotten history of medieval beguines.

In the middle of the Belgian city of Liège is a church that is forgotten. Its vaulted wooden ceiling is encased in broad stones, and slender stained-glass windows break up the otherwise austere façade. Despite the best attempts of nineteenth-century “restorationists” to enhance this gothic church, the building maintains its original characteristics: unadorned, ethereal yet functional, and resolutely standing at the center of residential, industrial, and educational quarters. But on a chilly Sunday in February 2022, the doors were as locked and the windows as dark as the other abandoned businesses, apartments, and former schools of art and architecture you pass as you wind through the neglected neighborhood.

This is the Church of St. Christophe, one of the first and most well-preserved churches associated with the beguine movement in the thirteenth-century diocese of Liège in the Lowlands (modern-day Netherlands, Belgium, and Northern France). The “founding” of the beguine movement was wrongly credited to the rabble-rousing priest Lambert le Bègue, a twelfth-century priest of St. Christophe’s, whose support of lay women who dedicated themselves to personal piety and service of their communities made him a notable, male supporter of these otherwise independent groups of devout women. Beguines were part of a widespread, yet rarely officially connected, women’s movement (Swan) in the central Middle Ages that challenged the religious authority of monastic orders and advocated for ecclesial reform through their embodied acts of worship and work. Like the medicant lifestyle Francis and Clare of Assisi, these mulieres religiosae (“religious women”) operated outside the bounds of formal monastic institutions and frequently in direct opposition to what many saw as spiritual and economic corruption.

Legal records reflect the importance of beguines to their medieval communities. Many wealthy people left houses and small grants of money and books to groups of beguines to provide them stable living situations and resources to use in their public acts of religious works. These properties were frequently joined together into beguine courts (or beguinages) where single, lay, religious women found a religious community outside the confines of the monastic cloister and served the secular community of the medieval city. Many beguines cared for the sick and dying, and evidence shows that they were preferred spiritual authorities at deathbeds as their prayers were believed more efficacious than those offered by priests. Other beguines established and ran hospitals to serve the poor, sick, and otherwise down-and-out. The most well-known of these hospital-administrating holy women is Elizabeth of Hungary whose particular care for lepers is a thing of legend.

Beguines never were formally organized, which made it difficult to understand the movement in the thirteenth century (and today). Church and civil authorities were generally perturbed by these women who did not fit neatly into the gender-specific religious vocation of nuns. The public nature of the semi-religious vocation of beguines put many of them in danger, the most notable being Marguerite Porete who was burned at the stake for her “unorthodox” mystical writings. Following Porete’s execution, the Council of Vienne (1311) officially outlawed the uncloistered, semi-religious lifestyle of beguines; while this law was inconsistently enforced, many beguine communities in northern Europe largely disappeared or were absorbed into more traditional monastic houses by the fifteenth century. The beguinages of the Lowlands survived the longest and even remain in some form today: the beguinage in Bruges is now a Benedictine convent that is open to the public, and both the Groot and Klein beguinages in Leuven are held in historic trust…and are simply stunning. The beguine court associate with St. Christophe’s, however, was not officially dissolved until the mid-nineteenth century. The former dwellings of the beguines around the corner from the church are barely indicated by a tiny blue sign.

The disappointment of not getting to really see St. Christophe’s was real. I had high hopes of being where some of the most compelling—and forgotten—women in church history worshipped God and served their lay community. I tried every door, read what was left of the commemorative plaques, and looked for signs of other pilgrims. My disappointment grew: no one was coming to church that day.

But I was struck by how familiar the locked doors, the missing congregation, and the neglected neighborhood was. On the one hand, Liège is one of many small European (and American) cities that have struggled to rebuild for a whole host of economic, political, and social reasons. On the other, this empty church is a stone monument to the forgotten stories of women whose lives have contributed to the vibrancy of religious life and practice for centuries.

Who were these medieval women? Why have they been forgotten, and what is the cost of neglecting their memory? Those are big questions with complex answers. But here are two of those holy lay women of Liège whose life stories—or vitas—testify to their memory:

- Marie d’Oignies

Considered to be “the first beguine,” Marie is known today through the vita written and popularized by her confessor Jacques de Vitry who came to Liège to meet the holy woman and learn from her. Marie’s life story gave official, orthodox status to women who existed outside of the traditional boundaries of holy women.

Born to a wealthy family in Nivelles, Marie exhibited great piety and a desire to serve God and prepared herself for a monastic lifestyle by rejecting luxurious clothing and playtime with her peers in order to pray. Her parents were not amused by Marie’s rejection of family wealth and status. According to a Middle English translation of Marie’s vita, her parents were so offended by her youthful piety that they married her off to John of Oignies. No longer a virgin but a wife, Marie could not take holy orders and enter a monastic institution. But, in a divine twist, John was won over by Marie’s example of piety and “promised to imitate his companion in her holy plan and in her holy ascetic life by giving up everything to the poor of Christ.” The couple devoted themselves to a chaste marriage and a life of good works and manual labor in and around the city of Liège—in other words, in public, outside the boundaries of the official power structures of the church, and in direct relationship to a wider community of lay people.

Marie was also known for her mystical visions of God, a number of them recorded by dde Vitry and interpreted as clear signs of her lay holiness. Her visions of Christ, Mary, John the Baptists were all verified by the tell-tale tears of compunction and compassion (a common occurrence in medieval piety, just think of our favorite English lay mystic Margery Kempe!). Through her work, prayers, and visions, Marie gained a reputation in and around Liège as being a source of divine understanding and lay holiness. Her vita popularized her public vocation further, and authorized other women who had similar religious desires and stories.

- Juliana of Liège (or of Mont Cornillon)

This true daughter of Liège and her sister Agnes were orphaned at five years old. Both sisters were placed in the care of the canon house of Mont-Cornillon. This semi-monastic household was modeled after a dual monastery where both men and women lived according to a monastic Rule but outside of the regulations of an established monastic order. No record exists to tell us about Agnes, but we do know that Juliana formally joined the canons at thirteen and began working in its leprosarium.

Juliana’s spiritual star rose after her first mystical vision at age sixteen. The image of a full moon with a grey slash across its face appeared to her repeatedly, and after consulting trusted advisors—male and female—she understood the vision to represent the need for a specific feast day for the celebration of Christ’s body and blood. Like many other religious people—especially beguines—Eucharistic devotion was central. Juliana’s vision reflected both the popular practice and a divine command to regularize the administration of the Eucharist and further elevate its importance in medieval spirituality.

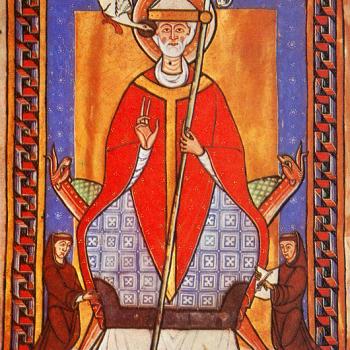

By 1225 Juliana was elected prioress of her house of lay religious folk, and with the help of her newly appointed confessor John of Lausanne instituted a specific holy day for the adoration and celebration of the Eucharist—what quickly became the Feast of Corpus Christi. She developed the liturgical office for the feast day with John, and in 1246 the bishop of Liège formally instituted the celebration.

Though her visions and personal-piety-turned-church holiday were authorized by a slew of ecclesial officials, Juliana was not welcome in her home town. Politics and devotional trends in Liège turned against her, and she later fled her beloved community at Mont-Cornillon—and her seat of local influence—for a community of beguines in nearby Namur where she later died. A cult quickly formed after Juliana’s death, and her body was buried in the part of the cemetery reserved for uniquely holy—even saintly—people. The Feast of Corpus Christi was authorized by Pope Urban IV in 1264, but Juliana was not canonized until 1869. Mont Cornillon Abbey remains a historical highlight of Liège, though one wonders how significant the story of Juliana is—or could have been—if local church politics had not turned against her.

Maybe it’s not surprising that a small church in the center of a seemingly abandoned section of a post-industrial European city would be closed; after all, Liége is in the process of renewing its economic and historic identity, and there are a number of other impressive religious and historical sights. Still, it was a sad to see how a small church and the people associated with it had been forgotten, even if by accident. The memory of the women of St. Christophe and the beguines of Liège seems to have passed away, worn down by the passage of time like the banks of the river Muese that borders the city. But if it was this easy to forget women like Marie d’Oignies and Juliana de Cornillon, what else have we forgotten?

For more information on beguines, see:

Laura Swan, The Wisdom of the Beguines: The Forgotten Story of a Medieval Women’s Movement

Anneke Mulder-Bakker, Mary of Oignies: Mother of Salvation

Jennifer Brown, Three Women of Liège

Walter Simons, Cities of Ladies