I have been a reader of the Anxious Bench since its beginning. The first post from Thomas Kidd that caught my attention was Slavery, Historical Heroes, and “Precious Puritans.” So when the Anxious Bench approached me about becoming “blogmeister,” I was thrilled.

I immediately felt the weight of responsibility for editing the Anxious Bench, and a little bit of anxiety too, especially concerning what my first post would be. The first post sets a tone. It reflects and projects what to expect from a contributor.

I dug through the archive to see what previous contributing editors, Kidd and Gehrz, wrote for their first contributions. Kidd’s first post, Ross Douthat’s Vanishing Christian Center, interacted with cultural commentary from a conservative New York Times columnist and functioned as public theology and philosophy—hinting towards Kidd’s alignment to political, social, and theological conservatism. I wasn’t terribly surprised by his post. However, I noted it offered no runway or introduction concerning himself or this new blog.

Gehrz published two posts his first day on the Bench: British Christians Debate Brexit and How Christians Can Love Their LGBT Neighbors? Start by Learning Their History. Both posts commented on present social and cultural crises, engaging them at the intersection of faith and history. In contrast to Kidd’s first post, Gehrz introduced his personality and perspective. He conveyed his role as a historical interpreter, and he approached these topics from his vantage point.

After observing the tactics of two outstanding historians, I entered into an internal wrestling concerning my first post. After the mental dust settled, I decided to write a methodological post, rather than dive into contemporary social commentary.

Truthfully, even as the events of yet another mass shooting took place, within an hour of my Chicagoland home, I called this tactic into question. Nonetheless, I think this is a wise decision. I would rather write a well researched response concerning the history of mass shootings, after having laboriously studied the long history of gun violence in America, rather than subject myself to shooting from the hip, if you will, by publishing a piece of punditry.

This tactic, of writing a methodological post, commends the vital idea that the historical enterprise is a personal enterprise that demands personal, patient reflection. Topics discussed by contributors at the Anxious Bench reflect their expertise and interests. Otherwise, this blog becomes a gaggle of pundits purveying ideological takes. That won’t do. I agree with John Turner’s recent assertion and parting caution. “The Anxious Bench isn’t an ideological blog.” Rather, our first-class scholars deliver incisive observations and commentary from the advantage of their expertise.

Second, with any shift in leadership, people want to know what else might shift. They seek a vision of what may be. No doubt this is the case for our regular readers, current contributors, and any potential contributors we wish to attract to this site.

Thus, it makes sense to offer a methodological reflection of what I hope the Anxious Bench will offer for readers in years to come. The span of this reflection will be three posts in length. It will follow a Western historical trajectory, one that mirrors the historical development and evolution of the Anxious Bench contributors and contributions.

Following a Western historical trajectory respects the historical integrity of what has been. Without endorsing this vector, it recognizes its reality. I do not wish to reinvent a historical past with a fictional revisionist history. Rather, we must reckon with what has been and how it must yet advance.

While the Anxious Bench’s beginning was White, male, and Western centered, it has evolved over time and will continue to do so. All the components necessary for continued progress are already present. The vision is a continued trajectory towards a global and diverse historical perspective.

To sum up, I hope our contributors will champion the irenic spirt of a pilgrim historian.

An Irenic Spirit

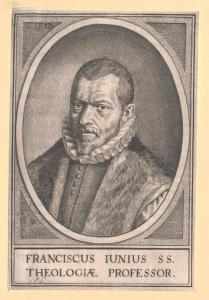

One of my Summer reading goals has been to dive deeper into the life and works of the late sixteenth-century Reformed Orthodox Scholastic, Franciscus Junius. I have been reading an English translation of A Treatise on True Theology (De Theologia Vera), while picking through parts of Tobias Sarx, Franciscus Junius d.Ä. (1545–1602) and Junius’s Eirenicum de pace ecclesiæ catholic.

My foray into studying Junius has been fruitful. It facilitated reflection on the significance of irenic historical work, and the importance of producing a faithful prolegomena to historical methodology, what I call pilgrim history.

My foray into studying Junius has been fruitful. It facilitated reflection on the significance of irenic historical work, and the importance of producing a faithful prolegomena to historical methodology, what I call pilgrim history.

Many readers may be unfamiliar with Junius. Franciscus Junius was professor of theology at the University of Leiden from 1592 until his death in 1602.

He was such an eminent theologian that King Henry IV of France invited him to Paris to provide theological council on Protestant affairs in 1591. Bear in mind, this is prior to that Protestant Bourbon King’s conversion to Catholicism in March of 1593 and the Edict of Nantes in 1598. If you recall, the Edict of Nantes provided religious toleration for Protestant citizens of Catholic France.

An even more interesting anecdote about Junius’s connections concerns a theologian he met at the wedding of Geertje Jacobsdochter in 1596. During the wedding banquet, Junius had a rousing discussion about the doctrine of predestination with one Jacob Arminius. The two proceeded to carry on confidential correspondence for the next seven years.

Upon Junius’s death, Arminius succeeded him as professor of theology at Leiden. Later, his ideas became subject to censure.  The Dutch Synod of Dordt, convened in 1619, codified Reformed Orthodoxy’s view of the doctrines of grace, and stifled the spread of Jacob Arminius’s ideas across Europe and the Atlantic. (Yes! The same year a Dutch slaver delivered a cargo of slaves to Jamestown.)

The Dutch Synod of Dordt, convened in 1619, codified Reformed Orthodoxy’s view of the doctrines of grace, and stifled the spread of Jacob Arminius’s ideas across Europe and the Atlantic. (Yes! The same year a Dutch slaver delivered a cargo of slaves to Jamestown.)

These two anecdotes hint towards the ecumenical and irenic spirit of Junius. He leveraged his theological acumen for public service to the King of France, and he patiently engaged in respectful disputation and theological reflection with an ideological opponent for years.

Junius, as public theologian, provides what I think is a fitting moral and social model for public historians, one which is worthy of mimesis (imitation). However, I think he offers even more from a methodological standpoint.

Pilgrim History

In his prolegomena of theology, A Treatise on True Theology, Junius popularized the concepts of archetypal and ectypal theology for the Protestant tradition. He subdivided theology into two divisions, which boil down to the notion that the finitude of human nature cannot comprehend the infinity of God (finitum non capax infiniti).

There is the knowledge of God in Godself that is only knowable to Godself, and there is knowledge of God that is communicated to humanity. Junius categorized the communicable, ectypal theology with three genus: 1) union with Christ (unione), 2) vision of the beatified (visione), and 3) revelation to the pilgrim (revelatione viator).

For the first class, there is knowledge of God privileged to the Son by virtue of his union to the Father. Even so, it should be noted that the human nature of the Son partakes in a limited knowledge of what the Father knows (ectypal theologie).

Likewise, the second class, the angels in heaven and triumphal saints, partake in a limited knowledge of what God knows. Their union with Christ and participation in the beatific vision privileges them with special knowledge and revelation of God. Yet, there are limits to their theological knowing as well.

The third class, pilgrims or viators, are members of the militant church on earth. Their theological knowing is removed yet one more step; of the three, pilgrims are rational creatures at the greatest disadvantage of knowing what God knows.

While some might express chagrin that the Son of God’s knowledge of God is limited, the veracity of this taxonomy can be verified by Matthew 24:36: “But about that day or hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.” Here we see Junius’s taxonomy at work: pilgrims (no one), the beatified (angels), and the Son do not know what only the Father knows.

I find Junius’s taxonomy to be suggestive for Christian historians. It invites Christian historians to conceive themselves as pilgrims on a journey to recover the past, to make its memory knowable to others. Configuring knowability of the past (history) with the same categories relieves pressure for historians to do the impossible, know everything and have absolute certainty about their knowability.

This taxonomy also gives pilgrim historians something to look forward to, a future hope fulfilled. They will participate in past knowing as beatified, triumphal saints, alongside the angels. Though there will be things hidden from them for which “they will long to look,” as revelation unfolds, they will watch it unfold on earth. Aspects of their past knowing will gain new clarity that comes only through the advantage of being beatified and a partaker in union with Christ. I expect a beatified historical imagination exists at a higher degree of excellence than a pilgrim’s historical imagination.

The Opportunity of Pilgrim History

The concept of pilgrim history invites historians to see themselves as those who have entered into the journey of classical Christianity. (I am more inclined to use the terminology of classical Christianity rather than the slippery and fraught terminology of evangelical Christianity.) As such, pilgrim historians 1) see themselves as pilgrims, 2) see past Christian historical figures as pilgrims, and 3) see other past historians as pilgrims.

Pilgrim historians see themselves as pilgrims. Embracing the identity of a pilgrim historian makes room for historical complexity. It also creates space for a pilgrim historian to develop as a historian. Pilgrim historians foster historical virtues, such as temperance and courage—two virtues that function complementary to one another.

Pilgrim historians see past Christian historical figures as pilgrims. This proposition aligns with Junius’s own assessment of redeemed humans in his theological prolegomena. The notion that past Christian historical figures are pilgrims invites historians to consider those subjects sympathetically and respectfully, in a similar manner to how one rightfully honors dead saints as a cloud of witnesses.

Pilgrim historians see other past historians as pilgrims. Each pilgrim historian looks to past pilgrim historians as pilgrims, recognizing their limitations and uncertainty. This, then, sets a fitting expectation on the self to admit to historical factual errors, which may have been made or revisit one’s own or another’s misconstrued historical interpretations. It resets expectations for how to treat past historical subjects.

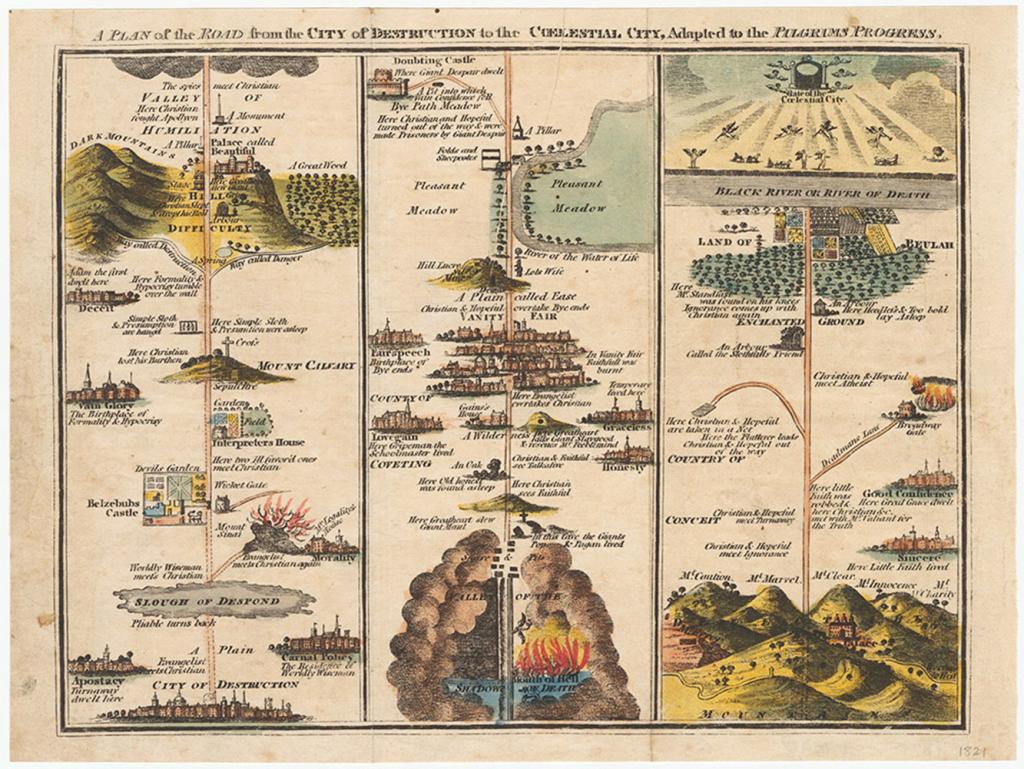

No doubt, as I have conveyed the idea of pilgrim history, I have conjured for some readers plot elements from John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. This is no accident. While this post functions as an introduction to pilgrim history, my next post will turn to a successor of Franciscus Junius, who popularized the idea of the viator (pilgrim). John Bunyan made pilgrim theology concrete and portable through his wildly popular publication, The Pilgrim’s Progress, an allegory about the figure of a pilgrim named Christian.

No doubt, as I have conveyed the idea of pilgrim history, I have conjured for some readers plot elements from John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. This is no accident. While this post functions as an introduction to pilgrim history, my next post will turn to a successor of Franciscus Junius, who popularized the idea of the viator (pilgrim). John Bunyan made pilgrim theology concrete and portable through his wildly popular publication, The Pilgrim’s Progress, an allegory about the figure of a pilgrim named Christian.

In my next post, I will discuss the print history of The Pilgrim’s Progress, the editorial development of its second part, concerning the pilgrimage of Pilgrim’s spouse, and how this text and its ideas migrated to the British Colonies and around the world.

You see, pilgrims are women too, and pilgrim history has welcomed women into the fold. Just as Thomas Kidd did when he invited Beth Barr to contribute at the Anxious Bench.

But the story does not end there. The Pilgrim’s Progress was one of the many works that influence a literary successor of Bunyan, America’s first African-American woman poet, Phillis Wheatley, who I will take up as the subject of my third post.

I hope readers recognize the trajectory and potential pilgrim history has for globally trafficking the values of diversity, in gender and race, for historical studies and leadership. These values will continually flourish at the Anxious Bench in coming years.