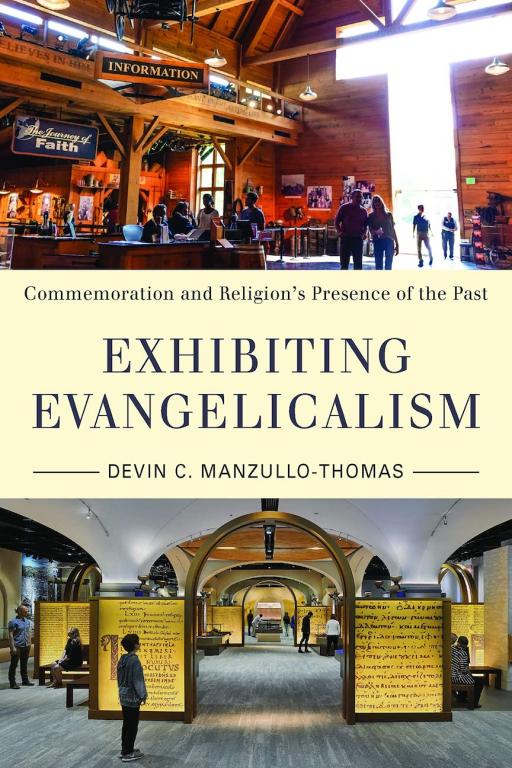

I’m pleased to welcome Devin Manzullo-Thomas to the Anxious Bench. He is assistant professor of American religious history, director of the E. Morris and Leone Sider Institute for Anabaptist, Pietist and Wesleyan Studies, and director of archives at Messiah University. What follows is a conversation we recently had about his new book, Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Commemoration and Religion’s Presence of the Past, which looks at how evangelicals have narrated themselves in museums. —David R. Swartz

***

DRS: What led you to research evangelical public history?

DMZ: In graduate school, one of the books I read in an Intro to Public History course was Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen’s The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life, an analysis of a nationwide survey of how Americans relate to the past. It chronicled the ways that people in the United States consume the past—books, documentaries, museums, etc.—and what they do with the past: make sense of their identities, build community, envision the future. It also explored the distinctive ways that different groups in American public life—African Americans, women, etc.—engage with the past.

While I found the book fascinating, I was quite bothered by one of the decisions that the authors made: they “did not ask explicitly about religion” (120) when surveying their sample. Although I recognize that a single monograph can’t do everything, it seemed to me that excluding from their study any considerations of the way that religious Americans engage with the past was a significant oversight. In my experience, religious Americans—especially the white evangelical Protestants around whom I grew up—were especially avid consumers of the past, with distinctive ways of thinking about the relationship between the past and their faith and about the role of history in American public life (e.g., the common belief in the church of my youth that America was a “Christian nation” and needed Christians’ deliberate custodianship).

To be fair, Rosenzweig and Thelen didn’t completely overlook these realities. In fact, they admitted that “a significant minority . . . [of] respondents forced us to see [religion’s] crucial role in determining how people think about and use the past” (120). And they gave direct attention to evangelicals, noting that “the historical vision of evangelical Christians is extraordinarily consistent and powerful” and that “few other Americans have such a vivid sense of how a specific set of past events guides their behavior in the present” (121). Still, it seemed to me that much more could be said about these religious Americans in particular. Fortunately, my graduate advisor agreed! I focused my dissertation on these questions, and from that project Exhibiting Evangelicalism was eventually born.

To be fair, Rosenzweig and Thelen didn’t completely overlook these realities. In fact, they admitted that “a significant minority . . . [of] respondents forced us to see [religion’s] crucial role in determining how people think about and use the past” (120). And they gave direct attention to evangelicals, noting that “the historical vision of evangelical Christians is extraordinarily consistent and powerful” and that “few other Americans have such a vivid sense of how a specific set of past events guides their behavior in the present” (121). Still, it seemed to me that much more could be said about these religious Americans in particular. Fortunately, my graduate advisor agreed! I focused my dissertation on these questions, and from that project Exhibiting Evangelicalism was eventually born.

I could have focused on a great many religious Americans who create museums, historic sites, and other spaces to make their history public. Catholics and Mormons certainly do this sort of thing. (Consider, for instance, Keith A. Erekson’s work on the history of the Joseph Smith Birthplace, or Emily (Davis) Arledge’s forthcoming history of American Catholic shrines.) But I chose to focus on Protestants, and especially on evangelicals, for two reasons. First, I had already published some scholarship on evangelicals, so I knew the general historical literature on this group pretty well… and I knew that very little had been said about the way that they narrate their history in public spaces. Second, I was particularly drawn toward the public history of a group that puts a great deal of emphasis on the mind. Beliefs, rather than rituals or practices, have always been paramount for Protestants and especially for evangelical Protestants. So why would a group that emphasizes cognition spend time, energy, and especially money creating spaces for exhibiting historical artifacts?

DRS: How did you pick your case studies? Or are these pretty much all the evangelical museums in the country?

DMZ: There aren’t that many museums owned and operated by evangelical Christians in the United States, but there are more than you might think. As I worked on this project, I determined early on that I would focus on institutions that claimed at least some level of identity as history museums. That led me to exclude sites like the Creation Museum and the Ark Encounter (which I nevertheless visited during my research!) since they are more like natural history museums. I could definitely have incorporated more historically oriented theme parks into the analysis, such as Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s wildly popular but ultimately ill-fated Heritage USA (which makes a brief cameo in Chapter 4). But the sites I chose were ultimately ones that I felt were historically significant—innovators in some sense—and/or ones with significant visibility or a national profile.

DRS: You show that early work in this area was largely driven by women. Who were they, and why haven’t we heard their names or stories until now?

DMZ: Two women played key roles in the creation of evangelical museums in the United States, at least in the version of the story that I tell in Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Helen Thompson Sunday and Lois Ferm.

Sunday was the wife of Billy Sunday, the famous Gilded Age baseball preacher. Born into an upper-middle-class Presbyterian family on Chicago’s west side, she was schooled in business administration by her father and deployed those skills early in her life, as when she started running her church’s large Christian Endeavor youth group at age 18. She married Billy in 1888, before he became a household name. By the time he died in 1935, Helen had amassed significant influence in the wider evangelical world. She had managed the many administrative and logistical aspects of Billy’s crusades, significantly contributing to his success, and had written a nationally syndicated newspaper column titled “Ma Sunday Speaks.” In keeping with what the historian Kate Bowler has argued about women in evangelical spaces more broadly, Sunday’s fame and authority were closely tied to her status as a wife and mother. Thus, after Billy’s death, her status was in jeopardy. How could she remain in the spotlight now that her tie to institutional power was gone? In part, Helen did so by curating Billy’s memory. She appeared onstage with post-World War II figures who claimed the evangelical label, such as Billy Graham, and when she did so she always spoke about her husband and his halcyon days, tying Billy’s legacy to these up-and-coming movement leaders. As she told the crowd at Graham’s 1952 crusade in Washington, D.C., “Billy Sunday was a great man. Give Billy Graham another [few] years and he’ll be a whiz too.”

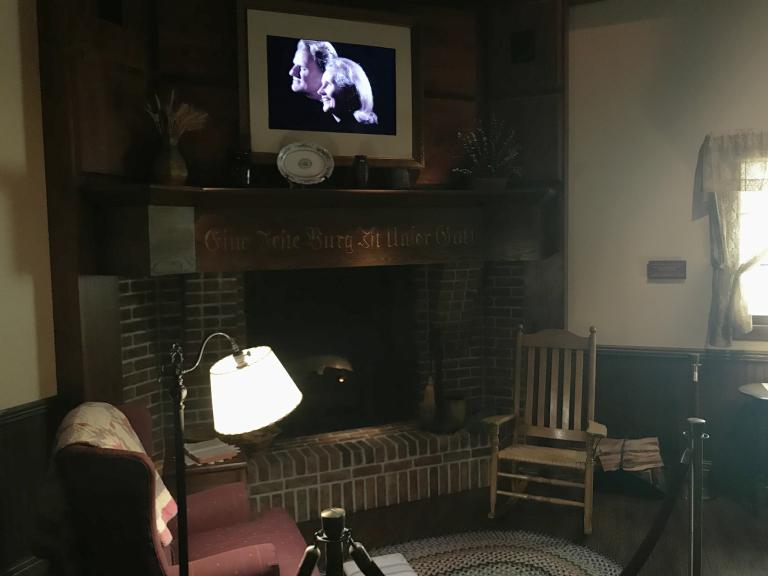

Sunday also retained her fame and authority by curating Billy’s memory in a material sense: by turning their home in the Midwest resort town of Winona Lake, Indiana, into a house museum. Starting at least in the 1940s and continuing until her death in 1957, Sunday opened her home—where she continued to live—to the many Protestants of all different denominations who flocked to the lake each summer. Her tours crafted Billy’s legacy in different ways, especially by displaying and highlighting material artifacts that emblemized certain aspects of his career. Indeed, Sunday’s work as a house museum curator in many ways set the stage for other experiments in evangelical public history.

Fast-forward a couple decades, to the 1970s—and to the work of Lois Ferm. A Houghton College graduate who eventually earned a PhD from the University of Minnesota, Ferm had already built a career as a librarian when she was tapped by Billy Graham in the early 1970s to help him brainstorm what he should do with the material legacy of his career—the large archive of artifacts, documents, and other records his organization had amassed in its two-decade existence. (Ferm’s husband, Bob, had been working for Graham’s organization in various capacities since the 1950s.) Ferm helped Graham to see the value of a museum and to strategize the purposes of such a site. Among other features, she argued that the site should not be a staid place for the exhibition of dusty artifacts. Instead, the museum should do what Graham had done at his many, many crusades: it should lead people to conversion. Ferm believed that by bearing witness to the grand history of American evangelicalism and to Billy’s personal story within that grander narrative, visitors might be compelled to give their hearts to Jesus.

Ferm was eventually removed from the project, sidelined by the all-male board of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. (My argument is that they were intimidated by her professional credentials and her proximity to Graham.) But her ideas were not erased. Indeed, the site that emerged after more years of planning and strategizing—the Billy Graham Center Museum, on the campus of Wheaton College outside Chicago—did exactly what Ferm advocated for. If you visit the Museum today, you’ll encounter a narrative of evangelicalism in America and you’ll hear the story of Graham and his ministry, but you’ll also find yourself in the Walk Through the Gospel exhibit, which uses sensory experience to replicate the biblical story of Christ’s death and resurrection. At the end of that exhibit hall, you’ll be invited to convert to Christian faith. Curators built on Ferm’s original idea, resulting in the museum that still stands today.

These women are fascinating—among my favorite historical actors in the story I tell in Exhibiting Evangelicalism. Unfortunately, as I note in the book, their work has been obscured. In part that’s because the Sunday house museum never became a national site (the Winona Lake Bible Conference to which it was connected filed for bankruptcy and dissolved about a decade after Sunday’s death) and because Ferm was pushed out of the project.

But I think their obscurity is also a historiographical problem—too much (though not all!) of the historical scholarship on evangelicalism has centered on male actors. That’s not the case in the historiography of public history, which has long acknowledged the role of women as preservationists, curators, archivists, and more. But unfortunately—again as I note in the book—these historiographies have not intersected or interacted. Part of what I’m trying to do with Exhibiting Evangelicalism is draw them together, show the resonances and connections over time.

DRS: You describe an “experiential turn” in public history. What does that look and feel and sound like at evangelical commemorative sites?

DMZ: Probably the best way to answer this question is to explain the Billy Graham Center Museum at Wheaton College, which was developed in the 1970s (at the peak of this “experiential turn” within the wider public history world) and finally opened to the public in 1980.

The museum in its original form contained a number of exhibits that engaged visitors’ emotions and gave them tangible experiences with the past. For example, in the exhibit on “The History of Revival and Evangelism in America,” visitors encountered traditional text panels, object displays, and timelines—but they also encountered a large, walk-through diorama of a nineteenth-century frontier revival tent, complete with long wooden benches (on which visitors could sit) and hidden speakers that piped in the sounds of a revival service: voices raised in worship, sentimental piano music, and more. The diorama invited visitors to imagine what might have happened at the service and, in this way, to identify with the people who might have attended it, thereby building historical knowledge through experience and emotion.

The most experiential exhibit in the original museum—which still remains today!—was the Walk Through the Gospel exhibit mentioned above. Visitors began this exhibit walking through a doorway shaped like the cross, into a series of labyrinthine, black-walled, dimly-lit hallways meant to symbolize Christ’s crucifixion and death. The only texts here were Bible verses, drawn from the gospels. Curators intended these hallways to evoke visitors’ feelings of guilt for sin and anguish over Christ’s sacrifice. But then visitors turned a corner, finding themselves in a blindingly bright room, the walls painted in hues of cerulean and white, enveloped in the sounds of “The Credo” from Bach’s B-minor mass. This room—known affectionately to visitors as the “Heaven Room”—was meant to signify Christ’s resurrection and ascension, and curators hoped it would fill visitors with feelings of joy and hope.

Similar experiential exhibits were incorporated into the museum’s mid-1990s renovation. For example, visitors to the museum today can stand in the pulpit that Billy Graham used throughout his career. They can literally put themselves in Graham’s shoes—standing where he stood, looking at facsimiles of the sermon notes he used. The walls surrounding the pulpit are even painted to look like a crusade crowd, so that you’re surrounded by listeners while standing in Graham’s stead. Again, the curatorial intent here is to get you to feel like Graham—to consider how you, too, might contribute to God’s work of evangelism.

DRS: I was fascinated by the decisive turn southward as your book progresses. Early on the key sites of evangelical public history were Winona Lake, Indiana; Boston, Massachusetts; and Wheaton, Illinois. In more recent years, you’re dealing with Charlotte, Washington, D.C., and other points south of the Mason-Dixon line. What does this geographical shift say about evangelicalism more broadly?

DMZ: This is a great question, and one that I wasn’t consciously aware of as I put the book together. But you’re right—there is a turn southward. My initial impulse is to think about this geographic move as one of market location: sites like the Billy Graham Library (which is different than the Wheaton museum) are going to draw more visitors in the Bible Belt than, say, in “secular” museum havens like Philadelphia or New York.

At the same time, I think the southward movement also has to do with respectability. The Museum of the Bible, which opened in Washington, D.C., in 2017, is situated right in the heart of America’s national commemorative landscape, just a stone’s throw from the federally operated Smithsonian museums that line the National Mall. Curators at the MotB strove for intellectual respectability, resisting efforts by major donors to get them to hand out tracts or incorporate other kinds of evangelistic methods (as sites like the Billy Graham Library do). They wanted the MotB to be taken seriously in the world of American public history.

DRS: I really appreciated your warning in the epilogue about not just deconstructing treasured narratives. You write, “If we are committed to revealing the inadequacies of certain historical imaginaries embraced by our visitors, what are we giving to visitors even as we take away their comfortable, deeply held ways of relating to the past?” What specific advice would you give one of your case studies?

DMZ: I think the biggest piece of advice I would give to these sites to embrace complexity. It seems to me that the public rhetoric of many evangelicals, especially evangelical leaders with large platforms, avoids complexity and nuance. That’s certainly the case at these sites, which—as I point out repeatedly throughout the book—minimize unflattering or problematic aspects of the histories they’re presenting. The Billy Graham Center Museum, for instance, in its historical exhibit on the history of evangelism and revival in America, stresses the work of evangelicals who called for the abolition of slavery… while conveniently leaving out the many, many evangelicals who supported the institution, often by appealing to the Bible. Similarly, the Billy Graham Library, in Charlotte, North Carolina, in narrating Graham’s life and ministry, emphasizes (one might say over-emphasizes) his achievements but doesn’t mention any of his failures, such as his unwavering public support for Richard Nixon, even after his role in the Watergate coverup was revealed, or the anti-Semitic language that Graham employed in some of his taped conversations with the president.

These aspects of evangelicals’ shared past are left out of the exhibit hall because they don’t advance what evangelicals believe are the purposes of history: they’re not inspirational or instrumental, at least not on the surface. They don’t invite visitors to embrace Christian faith. But I would argue that, if we accept evangelicals’ premise that history should have some sort of didactic purpose, then these aspects of the past do belong in the exhibit hall. They inform (or remind) visitors of an essential element of evangelical theology: sin. Evangelicals believe that all people—even evangelicals, even Billy Graham—are sinners, who sometimes act against God’s will and must seek repentance. Wouldn’t it make sense to showcase this very real (at least to evangelicals) aspect of human existence? Wouldn’t it serve the ultimate purpose of evangelical public history—to draw visitors to Christian faith—to remind us that, like people throughout history, we are sinners who need to confess our misdeeds and seek God’s forgiveness?