“My people are an apocalyptic people. We have resources to help you prepare for the end of times.” This was a sort of tongue-in-cheek greeting I developed for my academic friends, of the liberal or non-religious bent, after the election in 2016. While that year felt traumatic to those who felt sideswiped by the Trump election, the sentiment has only been magnified by the economic, health, environmental, political, and military crises since.

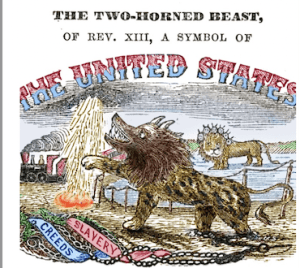

And yet, only recently have I felt comfortable using my denomination’s language and perspective in conversations with my non-churchy friends. Growing up as the devout child of a Seventh-Day Adventist minister, I was schooled early and thoroughly about our church’s prophetic beliefs. These beliefs included an emphasis on the way church history was predicted in the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation, and an anticipation of a coercive Roman Catholic Church supported by the political might of the United States. Heady stuff.

What separated us dramatically from many other Christian fundamentalists, who also focused on predictions of the end of times, was our belief that other Christians would persecute the small group of the faithful. This, along with our roots in the Radical Reformation (which included Anabaptists, Quakers, Mennonites, and eventually in the United States, Baptists), contributes to our profound conviction in the Establishment Clause (Separation of Church and State). While I was raised looking for “Signs of the Times,” those signs included any expansion of the Religious Right’s power.

In adulthood, my appreciation for the Book of Revelation expanded beyond its use for prophetic prediction into recognizing the hope and joy it expresses for times of trauma. At the Adventist university I now teach, I explain to my students that we all encounter times of trouble, and we need the resources and expressions of joy provided by the apocalyptic texts of the Bible. As a historian, I have studied Christians’ use of Revelation and other prophetic books, in the early modern period, and have appreciated how apocalyptic imagery has helped Christians, in crisis, make sense of difficulties.

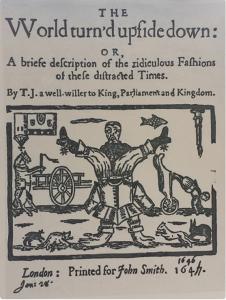

During the 1640s, a civil war was fought in present day United Kingdom. Parliament legally executed the English king, Charles I. After his regicide, the established church experienced an overhaul. Environmental change also contributed to what Geoffrey Parker has called a “Global Crisis.” Most Protestants involved in the civil war considered themselves in an apocalyptic moment. Many worried they might be fighting the literal Armageddon.

One radical group, known as the Fifth Monarchy Men, adopted their name from prophetic references in Daniel and Revelation, in which four kingdoms (Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome) would be followed by the Kingdom of God, or the Fifth Monarchy. Many such groups emerged in the space created by the economic and political upheaval of the English Civil War, included among these first documented groups considered as anti-state or in favor of communal wealth were the Quakers, Levellers, Diggers, and Ranters.

This period gave us the seeds of what we consider the modern world. Modernity contains within it the constant expectation of improvement, innovation, and change: Progress. This era generated a series of revolutions, notably the Industrial Revolution, and others, such as revolutions in finance, politics, chemistry, transportation, and, eventually, the information revolution. These successive re-makings of the world traumatized both the natural environment and the people who experienced them, especially those who experienced them under colonization and conquest.

Charles Taylor argues in A Secular Age that the story of progress and improvement, led by often-devout Christians, still resulted in a language and context that was less concerned with transcendence, less rooted in the book of Revelation. The stories and metaphors of the apocalypse, with its accompanying New Heaven and New Earth, where the Lamb that was Slain and the Prince of Peace ruled, were replaced with a more secular orientation, committed to things getting better in this world. However, as the twentieth-century dawned, small groups of Christian fundamentalists, including my tribe, the Seventh-Day Adventists, retained this language and the focus on the end of the world.

Peter J. Leithart reminds us, “when worlds die, we need something sturdier than the myth of technological and social progress.” Rapid transformations accompanied by plagues, wars, and economic crises led us to perceive ourselves as participants in the making of a new age, often one where we had nostalgia for the past and saw the present as a declension from those better days. As a Gen Xer, I’m inclined to recall the heady days in the 1990s, when we thought democracy and benevolent capitalism led to the whole world being united around freedom and prosperity. And yet.

The Book of Revelation, and, indeed, most scriptural apocalyptic literature, gives us hope for the future, rather than false romantic views of recreating some past golden age. It teaches us to be suspicious of earthly powers, but also that we shouldn’t be so consumed with them. There is another King who is concerned with justice, whose praises we should sing. We are called to have transformed hearts and to work for mercy and justice now, without placing too much trust in the power of the nation-state to enact such self-effacing charity.

When I share my apocalyptic worldview with friends today, especially those who aren’t primarily moved by a belief in the inspiration of the text that is sacred to me, I find myself reminded of those Quakers, Levellers, and Fifth Monarchy Men, who eschewed the power of the state to accomplish the work of living into the Kingdom of God. I call on the example of the nineteenth-century Seventh-Day Adventists, who called out the United States as one of the Beasts of Revelation, for its legal support of the enslavement of children of God, and whose pacifism made them the objects of suspicion and prosecution during World War One. Adventists continue to preach that the Second Coming of Jesus is near, while also building universities, orphanages, and the largest Protestant hospital system in the world.

The end of the world is scary. Most change causes anxiety. Yet, the vision of a world made new can fill us with hope and fire our imaginations. What might it be like to live into the New Heaven and the New Earth? Perhaps when the plagues and battles of Revelation feel all too close to home, we can start acting and planning and organizing, as if Revelation 21:3, 4 are true:

Now the dwelling of God is with humans, and he will live with them. . . and wipe every tear from their eye. . . for the old order of things has passed away.