George Whitefield canceled John Tillotson. Tillotson was one of the most influential ecclesial figures during the seventeenth century, on both sides of the Atlantic basin and continental Europe. He garnered the regard and friendship of philosophes like Voltaire and Locke. Increase Mather esteemed him. Jonathan Edwards referred to him as “one of the greatest divines on the other side of the question in hand”—the “other side” being Arminianism.

Many considered this former Lord Archbishop of Canterbury to be the hallmark preacher of his era. He was widely regarded for his moderating spirit and moral temperament. This well-documented fact had been a key argument in Tillotson’s favor prior to Whitefield’s campaign against him. Despite the credibility of Tillotson’s social network, his pastoral skill, uncheckered moral character, and transatlantic renown—Whitefield successfully canceled him during the Great Awakening.

How Whitefield Canceled Tillotson

During his first itinerant preaching tour of the colonies in America, Whitefield altered public opinion of Tillotson by what he said about him in front of large audiences, especially the influential audience at Harvard College. He leveraged personal clout with his social network of pastors and allies to the evangelical cause. The popular print publication of Whitefield’s journals recorded his arguments to cancel Tillotson, which circulated among a mixed readership of influential lay people and vocational ministers.

What Arguments Canceled Tillotson

During his address at Harvard College, Whitefield lumped Tillotson and Samuel Clarke together as author’s of bad books. Clarke’s 1704 Boyle lectures implicated him with charges of universalism and arianism. While Whitefield did not use the popular derisive, Arminian, to describe Tillotson, lumping him into a category with Clarke did just as much. Arminianism was not merely a soteriological counterpoint to Calvinism in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, but an epithet for anyone left of center and on the slippery slope towards universalism, arianism, or, heaven forbid, popery (Catholicism).

Whitefield also compared Tillotson’s knowledge of Christianity to Mahomet’s (The Prophet of Islam), hinting at his judgment of Tillotson’s unconverted state. If there was one threat greater to the Protestant cause than popery, it was Mahometanism.

Whitefield’s subtle deployment of ad hominem in both arguments proved to be an effective tactic in his campaign to cancel Tillotson.

Why Whitefield Canceled Tillotson

Tillotson represented the established church. To be clear, by established church I do not simply mean the Church of England. Rather, the established church constituted high-brow, elitist Protestantism of the British Empire, which could be any of the recognized denominations of the mixed-established church: the Anglican churches of England or Ireland, the Congregational churches of New England, or the Presbyterian churches of Scotland or the Middle Colonies.

In Whitefield’s view, the established church had drifted too far from the center and become corrupted. Whitefield believed an overhaul was necessary for the established church. He distrusted established church ministers and university scholars, challenging the authenticity of their conversions. He championed Methodist tactics, such as small group meetings and bible study. He advocated Reformed doctrine and heart religion, characterized with true conversion.

Tillotson was a convenient target because he couldn’t defend himself. He had passed away some time ago. Whitefield could disinter and defame the memory of Tillotson with little opposition, especially while in the outer rim of the British Empire—in the dissenting contexts of either New England Congregationalism or the Presbyterians of the Middle Colonies, or even the disorganized and fragmented Church of England churches in the Chesapeake colonies.

Whitefield effectively muted the memory of Tillotson in evangelical history. To this day, evangelicals know little to nothing about Tillotson, partly because Whitefield then occupied the celebrity pastor space Tillotson had once filled in British imperial history.

Josh Howerton, Canceled

I recalled afresh the story of Whitefield’s campaign to cancel Tillotson, after witnessing this past week’s calls to hold accountable megachurch pastor, Josh Howerton.

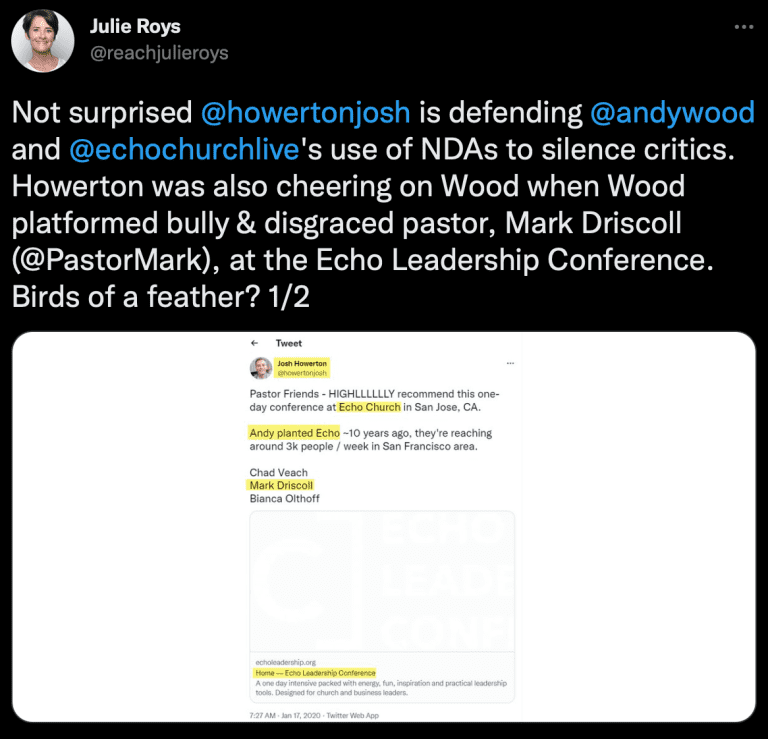

Josh Howerton (@howertonjosh), pastor of Lakepoint Church in Rockwall Texas, has been the recent recipient of ire for affirming Andy Wood as the incoming pastor at Saddleback Church. On July 28, Howerton tweeted an image of men laying hands and praying for Wood. This image incited an inferno of criticism.

Julie Roys (@reachjulieroys), of The Roys Report (TRR), entered the conversation early and shared a tweet of Howerton’s from the archive. Howerton’s tweet affirmed a one-day conference at Echo Church, where Andy Wood once-pastored. This January 2020 conference platformed Mark Driscoll, after he had relaunched into the public eye as a pastor, once again. Howerton redressed Roys and requested she tear down her post. The two sparred back and forth with an exchange of tweets. Central to the discussion was an article from TRR covering how abuse victim’s challenged the Vanderbloemen Group report, which cleared Wood of abuse charges and gave him the green-light to succeed Rick Warren at Saddleback.

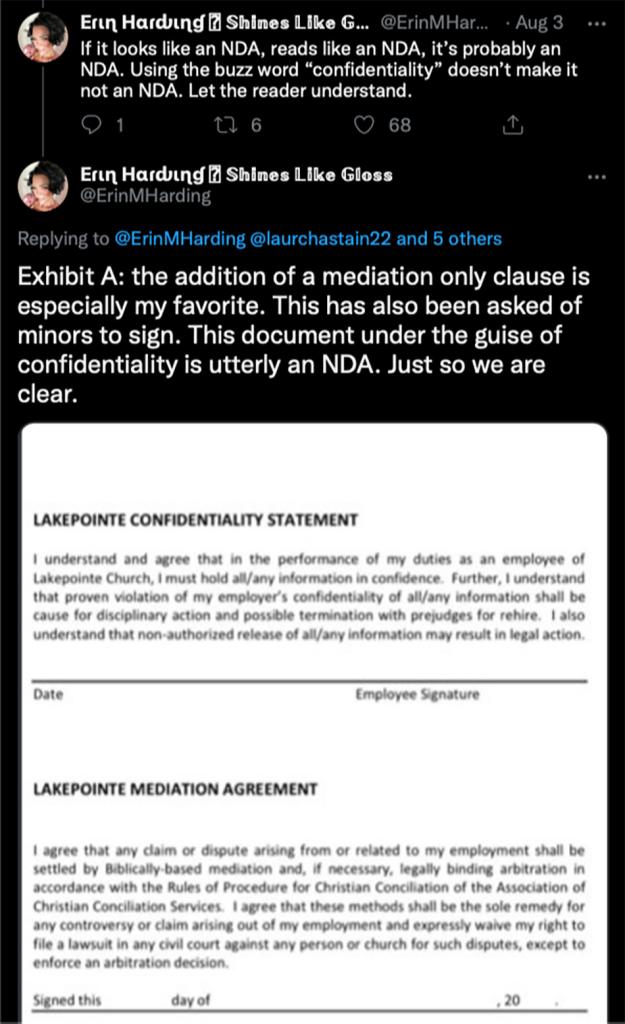

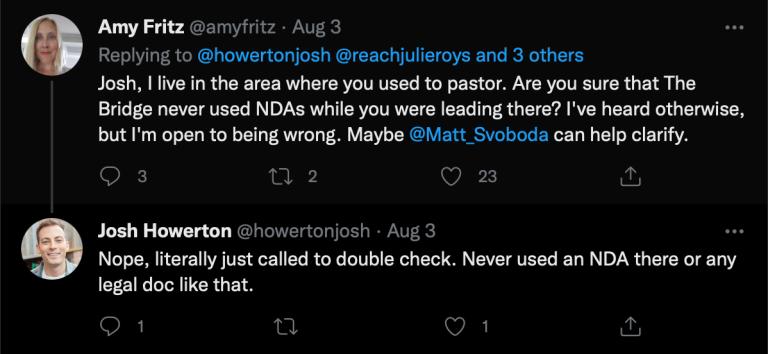

Howerton admonished Roys concerning the dangerous use of “concept creep” and fended off the charge that he supported the use of NDAs (Non-Disclosure Agreements). Concerning NDAs, Howerton boldly claimed, “Nor have I ever used one in any church I’ve pastored.”

At this point, Erin Harding (@ErinMHarding) stepped in and presented a piece of evidence to the contrary. It was an employee agreement, in use at Lakepoint Church since 2020, that included a confidentiality statement and mediation agreement.

This evidence was supplied after Amy Fritz (@amyfritz), an abuse survivor from Dave Ramsey’s financial ministry, pressed into the conversation with Howerton to clarify his meaning of NDA and his history of using one at The Bridge, where Howerton formerly pastored.

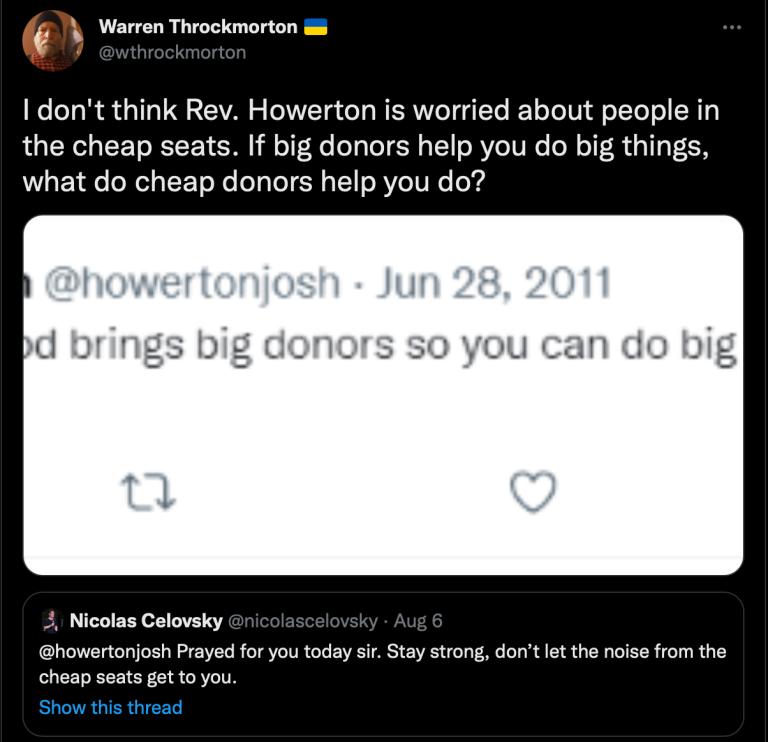

At various points, other defenders of church spiritual and sexual abuse victims brought forward their concerns. Boz Tchividjian (@BozT), a lawyer who defends abuse victims, clarified the criteria of what constitutes an NDA. Sheila Gregoire (@sheilagregoire), author of The Great Sex Rescue, posed the notion that ministers, who affirm abusers like Driscoll or Wood, themselves, may be disqualified from ministry. And Warren Throckmorton (@wthrockmorton) pulled from the archive a 2011 tweet from Howerton that affirmingly quoted Mark Driscoll, who said, “Sometimes God brings big donors so you can do big things.”

The Throckmorton tweet quote tweeted (QT’d) an admirer of Howerton, who had come to his support. Nicolas Celovsky (@nicolascelovsky) publicly shared how he had prayed for Howerton that day and encouraged him to not “let the noise from the cheap seats get to you.” Celovsky’s tweet elicited intense criticism about social status and hierarchies from multiple corners of Twitter, including a clever subtweet from Scott Coley (@scott_m_coley): “Jesus spent all his time in the cheap seats.” Howerton and Celovsky offered a correction that “cheap seats” referred not to social hierarchy but to the point of view of those not directly involved in a situation (appealing to the Urban Dictionary definition). Howerton rallied support from many, including a public statement from Daniel Darling (@dandarling), thanking Howerton for his faithful gospel ministry.

Nonetheless, after days of enduring what Howerton and his supporters might be perceive as a campaign to cancel him, Howerton seemed ready to withdraw, admitting he needed to focus on church ministry until he had margin to reflect on what had recently unfolded. His last thread included the forlorn conclusion of whether he could “stay on the Twitter streets or need to move.”

Cancel Culture Is a Feature of the Evangelical Story

Observing these events unfold on social media over the past week and comparing them to a story from the evangelical past has proven beneficial for me. It’s provided me objective space to reflect on the panoramic picture unfolding in the evangelical story. It has created a safe distance for me to study and recognize parallels to the past. It’s helped me consider the problematic elements and the beneficial function of cancellation, and explore and discern what constitutes cancellation. Whitefield engineered a damaging and problematic campaign to cancel Tillotson. On the other hand, Howerton has been confronted and called to account for his incautious support of an abuser. His failure to heed correction may indeed lead to cancellation.

When others hint at cracks in evangelicalism’s foundation or allude to the fragmentation of evangelicals, I perceive isolated tremors, like the Howerton debacle, as prescient warnings of impending seismic activity afoot for evangelicalism. I won’t forecast what rupture will ultimately cause a permanent alteration in the evangelical landscape. I’ll leave that to evangelical meteorologists superior to me. What I will do in this, and other successive posts, is point us to patterns from the evangelical past that parallel features we witness today.

You see, despite what many might assume, cancellation is not novel to twenty-first century evangelicalism. Canceling pastors is as old as the evangelical story. George Whitefield, who John Stackhouse has recently depicted as one among the quintessential ur-evangelicals, trail-blazed evangelical cancel culture when he canceled John Tillotson.

The spectacle of the public fall of celebrity pastors has indeed escalated over the course of the twenty-first century. There are features of the information and digital age that has accelerated this phenomenon. The rapid and real-time capacity of digital technology has collapsed the length of time in which a celebrity pastor’s downfall may occur. In the twenty-first century, figures like Howerton might be canceled in a week or even a weekend. All it takes is the right circumstances and a league of people to mobilize in the effort of holding accountable those who have not been brought to account for their indiscretions.

The recent attempt to hold Howerton accountable is just one instance in a growing pile of attempts to hold twenty-first century celebrity pastors accountable, and the pile will likely only grow higher in coming days.

The Function of Christian Cancel Culture

Why will the count escalate? A league of public personalities, who seek justice for the spiritually or sexually abused, has developed. This collective has organized itself and acts in concert to do what evangelical churches and their leadership have failed to do. This article has introduced you to a number of the personalities that are part of this loose coalition. By no means have I mentioned them all.

Many of those invested in seeking justice for the abused were themselves victims in the past. Their stories of suffering drive their participation in the righteous cause against abuses. Their opponents perceive that this pre-existing condition inhibits them from judging circumstances objectively and impartially. Of course, this riposte is insufficient at best.

Cancel culture will exist and continue to exist wherever adequate and equitable church discipline does not exist. It has become a necessary last resort, and a populist technique, when the God given mechanisms for accountability in the church have failed. As the case of George Whitefield and John Tillotson demonstrates, cancellation is no novel, modern, digital age phenomenon in evangelical history. It’s a ubiquitous feature of the evangelical story. I can produce numerous stories where evangelicals from the right or left have had to resort to cancellation. Some reasons are noble and necessary. Others are not. These episodes are portents of impending ruptures. They are tremors indicating seismic activity is imminent.

It’s possible that one of the unexpected outcomes of The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill podcast has been that it contributed a well-produced case study for how present-day evangelicals may mobilize and engineer an effective contemporary, cancellation campaign—in order to challenge, confront, and resist the evangelical church in the US. In the wake of this podcast, there seems to have been an escalation in campaigns to cancel pastors and confront church leadership. People who listened to the podcast and resonated with it, found one another on social media. They have organized and are collaborating to do what the evangelical church has failed to do. They are confronting injustices in the evangelical church in the US and calling it to account for those abuses. They are working systems that have become necessary, where other systems have failed.

While some might argue that these efforts are part of a conspiracy to undermine, subvert, or wreck evangelicalism, it’s altogether more likely that those in league are simply part of the harrowing legacy of its revivalist tradition.