Today we welcome a guest contribution from Patrick Leech to the Anxious Bench. Patrick Leech (@PatrickCLeech) is a historian of the global Cold War, with an emphasis on Hungary and Eastern Europe. He is a doctoral student at Baylor University, researching global resettlement of Hungarians from 1956–1957.

The collection of podcasts I subscribe to has repeatedly featured the same guest, Eboo Patel, discussing his new book and interfaith work. In each interview, Patel has proposed a provocative thought experiment: What would be the consequence if all religious institutions in society shutdown today? His point being that faith-based institutions, especially those in the United States, make massive contributions to civil society. Faith-based institutions often do so in ways that promote human flourishing, while fostering diversity, and as such, they serve as models, for how pluralism can successfully function in the twenty-first Century. As someone who studies the Cold War and socialist Hungary, this thought experiment is not hypothetical; we know the consequences of what would happen if all religious institutions shutdown because it happened in Hungary.

In August 1949, the Hungarian Working Peoples’ Party adopted a new constitution, creating the Hungarian People’s Republic; enshrined within that constitution was the separation of church and state. Prior to 1949, churches in Hungary enjoyed substantial political and cultural influence in exchange for supporting whoever was in power, including the fascists. As a result, much of the population perceived churches in Hungary as corrupt, and they supported Communist-led efforts to remove churches from formal political power. Church leaders fiercely resisted this, for they controlled massive amounts of land and over half of the educational system. However, the state used its full power to subjugate the churches, along with the rest of society in 1949 and again in 1956.

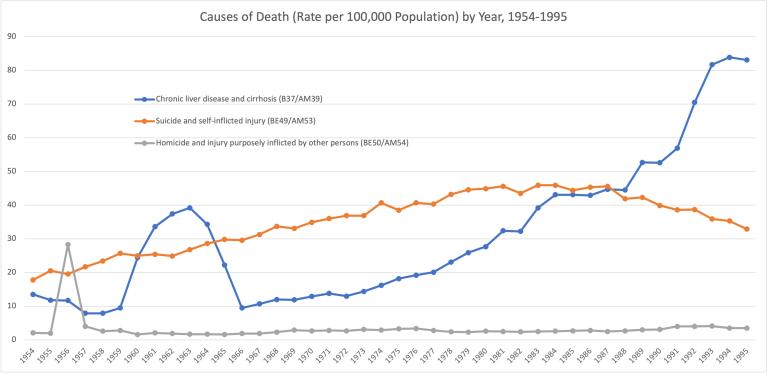

In the 1960s, the state introduced more permissive economic and social policies, but it kept tight control over churches. Dubbed Goulash Communism, these policies tried to buy popular support, by allowing some private economic activity, promising higher standards of living for everyone, through industrialization and generous state benefits. Although these programs succeeded economically, they coincided with drastic increases in alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide. By the early 1960s, Hungarians experienced the world’s highest rates of suicide—including among children and adolescents—and remained atop that list for two decades, a rate which rose by 70%. During this same period, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related deaths dramatically increased, as did other indicators of social fragmentation, like divorce and drug abuse.

These social problems exploded despite substantial economic improvement, contradicting Marxist ideology, which rooted social problems in economic disparity. Instead, Hungarian society entered a vicious cycle of despair, loneliness, and dissatisfaction that reinforced social fragmentation and personal isolation, which contributed to addiction and suicide. In 1893, sociologist Emile Durkheim called this cycle anomie, linking it to massive socio-cultural changes, such as industrialization and modernization. According to Durkheim, these processes stripped an individual’s life of meaning and purpose, while displacing them from traditional social support networks. Thus, societies suffering from anomie exhibited markers of personal dissatisfaction, such as high rates of suicide, divorce, and alcoholism. To answer Patel’s question, this is what happens to a society when purpose-giving institutions, like churches, vanish from civil society.

We know this because, after years of unsuccessful efforts, the state cited these social problems as justification for readmitting religious institutions into civil society, despite the party’s persistent opposition to religion. In 1977, the state adopted an alliance policy that included the normalization of church-state relations based on shared interests. Soon churches sought to address social problems with workshops, training, and even evangelistic tours by Nicky Cruz, David Wilkerson, and Billy Graham. Moreover, a new Catholic service order formed, a reversal of the 1950 expulsion of all religious orders. Frequently, state leaders participated in these events! These efforts did not magically fix the problems in Hungarian society. Rather, they seem to have injected a slow-acting antidote: hope. While hope is hard to quantify, the plateauing rate of suicide suggests these programs blunted despair.

This brings us back to the present and the United States. Sadly, the United States is experiencing despair and fragmentation, problems worsened by the pandemic and political turmoil. While the causes may differ from those of socialist Hungary, these symptoms sound eerily familiar. The United States is facing high rates of suicide, along with abuse of drugs and alcohol, sometimes in the toxic mix labelled “deaths of despair.” Some people exhibit the social dislocation of anomie through grievance or intolerance. The most tragic examples of this phenomenom include young men, who commit acts of mass violence, like the shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde. Additionally, many recent books anchor today’s political and social hyperpolarization to social fragmentation. Moreover, the continued relevance of Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone reminds us that anomie has deep roots in the US, even as recent conversations about deaths of despair or the effects of social media have increased our awareness.

The lessons from Hungary are two-fold. First, for societies in the grip of anomie, churches living the gospel’s call to hope, love, and connection offer unique solutions that no government program can. The Hungarian experience shows us that when churches engage society with hope and love, change can happen. Second, the government cannot solve all social troubles. Instead, a strong, vibrant, diverse civil society is needed.

Despite the claims of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and other Christian Nationalists, pluralism is not the cause of problems in the US or Hungary; nor are Hungarian statist policies, past or present, a model for promoting the common good. Rather, the actual problems are the failure of social institutions, including churches, to meet peoples’ needs. Which brings us back to Patel. He argues the US does not need better critiques from the left or the right. Rather, it needs people to come together to help others, despite their political differences. Unusual for this moment, he is optimistic because ecumenical and interfaith organizations can serve as a model for solving shared problems, despite sharp disagreements about core beliefs. Patel points to the recent past of the United States for a model forward, while socialist Hungary provides an example of the consequences of failure. The question is: Which path will we choose?