Yesterday was the 116-year anniversary of the Atlanta “Race Riot”. I put “race riot” in air quotes to affirm what a good friend of mine tweeted yesterday: that we should stop calling race massacres race riots. Indeed we should. But I would take it a step further. They were mass lynchings. Whether we consider the “riots” in Colfax (1873), Wilmington (1898), Atlanta (1906), Slocum (1910), East St. Louis (1917), Chicago (1919), Ocoee (1920), Tulsa (1921), Rosewood (1923), or others of that period, what we are looking at are not fights. They are massacres and public, spectacular displays of white supremacy. In other words, they were spectacle lynchings.

But what is so wrong with the language of “race riots”? The most egregious failure of the language is that it assumes or argues for a level of mutuality that was not present in these events, as though white and Black communities were angry with each other and fighting in the streets. More often, it was the case that any aggression that white people faced was from Black people defending themselves. Colfax and Atlanta are perfect examples.

After the Civil War, we saw the period of Reconstruction: perhaps the only prolonged period in American history where there was significant governmental effort toward the creation of a multiracial democracy. A sustained federal occupation for decades could have secured Black political participation and perhaps legal equality. But that was not to be. The period was cut short by Rutherford Hayes as well as by the continued application of terroristic violence. One such example happened in Colfax, Louisiana where after the 1872 gubernatorial election, a mob of white men killed likely more than 100 black people, many of whom had been recently freed men. After newly freed people threw in their lot with the Republican candidate and white voters sided with the Democrat, the Republican winners, fearing that Democrats would take the government by force, occupied the courthouse on Easter Sunday, 1873. These fears were not unwarranted.

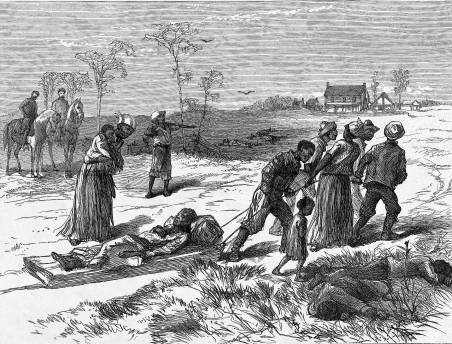

A white mob attacked Colfax’s courthouse and the people surrendered. Surrendering did them no good, however. After they surrendered, the men, women and children present were massacred. Those who tried to hide were killed. Those who tried to run were killed. One black man, Levi Nelson, survived to tell his chilling testimony: a story of 300 Black people, perhaps only half of whom were armed, huddling in a courthouse and being fired upon by a mob armed with cannons and guns insistent on their death. 98 men were indicted for the massacre, but 9 men were charged collectively with one murder. There were two trials and everyone ended up getting away. When the federal government appealed the case, it became the case, US vs. Cruikshank in 1875, where William J. Cruikshank was one of the members of the mob. In its decision, the Supreme Court sided with the mob, ruling that the 14th Amendment’s Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses applied only to actions of the state, not to violations of civil rights by individual citizens. This is what rings in the ears of any Black person who hears appeals to “states’ rights”: this was precisely the argument constantly marshaled to neuter attempts to actually protect Black life in states that were heavily invested in snuffing it out. Here, we have a depressing combination of individual, communal and systemic violence.

This was not a riot. It was a terroristic assault, rooted not merely in blind hate, but rather in something much more mundane and the true root of racial violence: vying for social power. Black people can’t vote for your opponent if they’re not alive to make it to the polls. Such a way of thinking undergirded the terroristic campaigns of the Klan as well. Calling Colfax a riot does the Black men, women and children who suffered its terroristic violence a profound injustice.

A similar situation took place in Atlanta thirty years later. The Georgia gubernatorial race in the summer of 1906 set the stage for the brutality of that September. Democrats, as was their platform in this period, foregrounded Black disenfranchisement as necessary while in the background, newspapers sensationalized the news in a way that they knew would sell papers: through sex and violence. In this period, however, one of the most effective ways to set a crowd off was to replay images that precipitated lynchings: namely stories about Black men assaulting white women. On Saturday, September 22, newspapers reported four attempted rapes of this nature. That night, mobs formed, indiscriminately attacking the Black community of Atlanta. Homes and businesses were destroyed. But even more egregiously, it was not publicly marked until its 100 year anniversary in 2006. That is, in the minds of white people, it remained an ignored piece of history. For Black residents, however, as was the case in any of these massacre locations, these events served as a constant reminder of the capability of their neighbors.

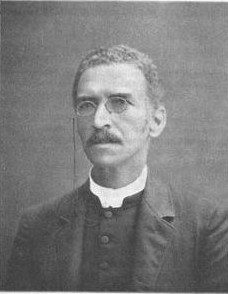

These two examples draw attention to what is one of the most significant arms of the cycle present throughout American history often manifested by racial capitalism: a cycle of economic and political exploitation, violent enforcement of that exploitation, and justifying racialized narratives. This is the violent enforcement arm, the proverbial stick that hovered over the heads of Black communities in the South in the late 19th and early 20th century particularly. Colfax and Atlanta were not blind, frenzied acts of mass hate. They were more intentional than that. The mere existence of Black people invested in their own political and economic success was a threat to a white supremacist status quo and mass lynchings were a tool of self-protection for that status quo. Francis Grimké lamented such a state of being in a sermon on the Atlanta mass lynching:

To have a dark face is to become a target for abuse, for insult; is to give every white man the right to maltreat you, to kick and cuff you, and spit upon you. And if you resent it, if you dare to protest, to intimate that you have some rights that you would like to have them respect, the mob spirit is instantly evoked, and your brains are knocked out, or you are shot to death or burned at the stake…Everywhere the black man is beset by perils. He doesn’t know what a day may bring forth; he doesn’t know what day he may be shot down, or some member of his family, or some friend or acquaintance murdered.

This was not an ethos precipitated by riots where political protest escalated into violence; rather, it was precipitated by the continuous threat and application of white supremacist violence. We would do well to call massacres and lynchings what they are and not shy from the brutality of the language. This is an abyss that every American, especially, must stare into, for it shaped the country in which we live. We have an extensive history of political power being snatched through the slaughter of the defenseless. We have an extensive history of people suffering attacks because they “stepped out of place”. The racial violence that we witness in our history was not ultimately in the service of hate; it was ultimately in the service of domination and exploitation. If we are to cut it off at the root, we must see it for what it is…and call it what it is. It is not a coincidence that most of the massacres narrated or referred above happened on or around election days. In this country, race has always been about power.