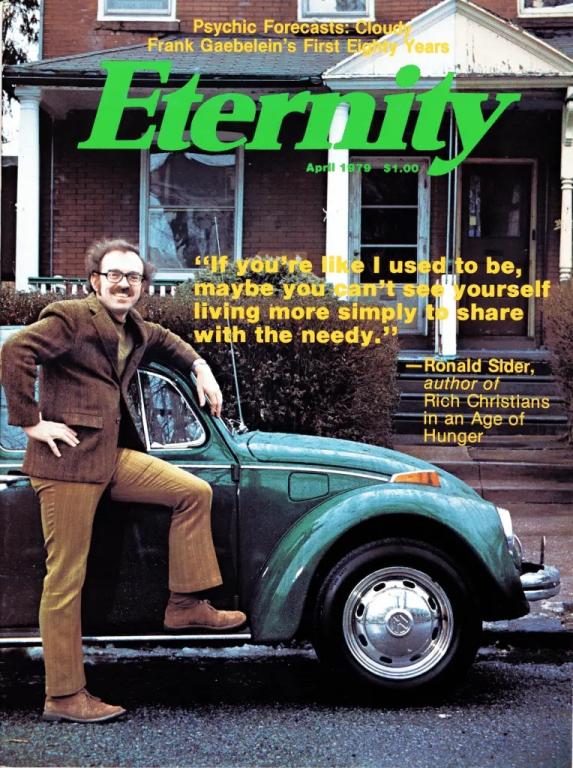

When Ron Sider died last month, the lede in many tributes was his 1977 book Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger. I agree with that editorial decision. Sider’s commitments to economic justice (and peace) are his greatest personal legacies.

Less emphasized in the tributes were his efforts—seemingly successful at first—to organize a politically progressive movement that might challenge the conservative status quo. Over the next few months, I will be chronicling his leadership of the evangelical left in the 1970s and what its failure says about evangelical politics in the postwar era.

I begin today in 1972. Sider is not yet a political activist. He’s an unknown history professor at Messiah College in rural Pennsylvania. But he is about to get caught up in the Richard Nixon-George McGovern presidential contest in ways that will propel him to evangelical prominence.

***

In the 1960s politically progressive evangelicals were “scattered, lonely, and frustrated,” according to Reformed philosopher-theologian-seminary professor Richard Mouw. I tell many of their early biographies in my book Moral Minority, but suffice it to say that they came from diverse traditions, nurtured different impulses, and pursued disparate projects. In the early 1970s, however, they began to find each other. In 1970 African-American evangelical Bill Pannell traveled to Costa Rica to tell Latin Americans about the black experience in the United States. In 1972 Mouw himself helped organize the annual Calvin College Conference on Christianity and Politics. Samuel Escobar of the Latin American Theological Fraternity brought his vision of global justice to InterVarsity circles. Wheaton College students joined Jim Wallis at rallies against the Vietnam War. Mark Hatfield gained headlines as a contrarian U.S. senator. Sharon Gallagher and the Christian World Liberation Front enjoyed growing prominence as practitioners of a third way of intentional spiritual community. Carl Henry, already well-known for his book The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism, continued to repudiate quietism in the pages of Christianity Today.

Organizationally, the evangelical left got launched in August 1972. Messiah College professor Ron Sider opened a letter asking for donations toward Mark Hatfield’s re-election campaign for the U. S. Senate. After sending in some money, Sider asked himself, “Why can’t we do the same thing for the Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern?” In September, Evangelicals for McGovern (EFM) was born among a small circle of evangelical social activists in Sider’s Philadelphia home. As the effort turned national in the following months, many in both the press and the evangelical communities took note. Not only was this the first explicitly evangelical organization in postwar American politics to officially support a presidential candidate, EFM was endorsing a liberal Democrat.

Organizationally, the evangelical left got launched in August 1972. Messiah College professor Ron Sider opened a letter asking for donations toward Mark Hatfield’s re-election campaign for the U. S. Senate. After sending in some money, Sider asked himself, “Why can’t we do the same thing for the Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern?” In September, Evangelicals for McGovern (EFM) was born among a small circle of evangelical social activists in Sider’s Philadelphia home. As the effort turned national in the following months, many in both the press and the evangelical communities took note. Not only was this the first explicitly evangelical organization in postwar American politics to officially support a presidential candidate, EFM was endorsing a liberal Democrat.

Progressive evangelicals found McGovern’s political ideology far more congenial to their own reformist impulses than Nixon’s. “We like the way McGovern is getting his feet dirty. He’s concerned about hunger, war, poverty and ecology,” explained Wheaton professor Robert Webber to a Newsweek reporter. Jim Wallis, who served as a regional manager for McGovern’s campaign, called the candidate “a first ray of hope in the midst of widespread despair.” Official EFM documents praised McGovern’s evangelical background, his religious rhetoric, and his stances on school busing, poverty, and the war. “A rising tide of younger evangelicals,” asserted an early news release, “feels that the time has come to dispel the old stereotype that evangelical theology entails unconcern toward the poor, blacks and other minorities, and the needs of the Third World.”

Animus against Nixon and conservative politics as much as resonance with McGovern motivated EFM. While some students and professors at Calvin College rallied with considerable enthusiasm for the McGovern candidacy in a student election, it became clear when students heckled and booed Nixon’s running mate Spiro Agnew at a nationally televised campaign event that this support was in large part a protest vote against the incumbent. Indeed, EFM devoted little effort to parsing the particulars of McGovern’s planks. In an article entitled “Seven Reasons Why to Elect George McGovern,” most of the reasons centered on how McGovern’s policies were not Nixon’s. More than supporting McGovern—they could only muster weak superlatives such as “candid and decent”—members of EFM mostly scorned the president.

Nixon troubled progressive evangelicals for reasons domestic and diplomatic. He had failed to maintain civil rights progress, and his southern-strategy campaign was saturated with “law and order” rhetoric. In an EFM fundraising letter Sider decried “policies, however camouflaged, which are designed to slow down or reverse racial progress” and condemned Nixon for profiting from “a white backlash.” In addition to criticizing Nixon for race-baiting, EFM charged him with expanding tax loopholes for the rich. Nixon also was responsible for the deaths of thousands of American soldiers and even more deaths of Vietnamese innocents. Operation Linebacker, the massive American aerial attack in the summer of 1972 that pushed back the Viet Cong’s Easter Offensive, “has bombed just as many Asian men, women and children into eternity.” Disregard for non-American casualties smacked of “Western racism.” Such policies, EFM maintained, “grieve the one who had his eternal Son become incarnate in the Middle East.” McGovern was the default choice for progressive evangelicals, who excoriated Nixon throughout the 1972 election season.

As the presidential contest entered its final months, EFM embarked on an offensive. Hoping to sway as many evangelical voters as possible to McGovern’s side, Sider sent over 8,000 letters to evangelical leaders. Support for EFM quickly spread. A woman from North Carolina wrote, “You don’t know how thrilled I am to get your letter.” A graduate student from Ohio University wrote of his disgust with Nixon’s “sordid and totally hypocritical tugs at the sentimentality of Americans—especially Christians with his entourage of Billy Grahams, Norman Vincent Peales, and other Pharisees and anti-commies.” He declared his intent to “proselytize for McGovern.” A Pentecostal man from Chicago declared his support for McGovern and EFM. A 1956 graduate of Wheaton College praised EFM, complaining that a recent commencement address at his alma mater was “concerned entirely with how social justice was bad and contrary to true justice, which was not defined.”

Of the hundreds who sent EFM $10 and $20 checks, most fit the profile of the new evangelical left. Many held key leadership positions in flagship evangelical organizations such as Wheaton College, Gordon-Conwell Seminary, Fuller Seminary, Christianity Today, and World Vision. Additional support came from other quarters of evangelicalism. Some faculty members from Wesleyan colleges Olivet Nazarene, Asbury, and Taylor sent support and served on EFM’s Board of Reference. Members of ethnic and confessional schools, just entering the neo-evangelical orbit, also contributed. Reformed representatives included Stephen Monsma and Richard Mouw of Calvin College and Deane Kemper of Gordon-Conwell Seminary. Supporters from Anabaptist institutions included Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Messiah College, and Mennonite Central Committee. Mennonite voluntary service centers in rural eastern Kentucky prominently displayed EFM letters on their bulletin boards. The core group also included prominent black evangelical activists Columbus Salley and Tom Skinner, who served as vice-chairman of EFM. Most members, however, were white, male, middle-class, and educated. Many had attended Billy Graham crusades and still respected the evangelist’s outspoken evangelical faith—but had grown increasingly embarrassed about Graham’s close ties with Nixon. EFM’s response to Graham’s barely veiled support for Nixon was that “our organization is the message that Billy Graham does not speak for all of the nation’s evangelicals.”

As the campaign wore on, however, it became clear that Graham did speak for most evangelicals. After a month of fund-raising, EFM received only $3,500 from about 220 contributors. While the novelty of a northern-based evangelical organization stumping for a Democratic president generated more publicity than actual influence and made for good copy in publications such as Time, Newsweek, and Christian Century, EFM earned less than adulatory praise from the general evangelical constituency. A faculty member at Washington Bible College told EFM board members, “I am amazed, and indeed dismayed that I should be asked by evangelicals to support this movement in the light of the type of campaign which has been conducted by the men whom you are endorsing.” Her primary complaint was that McGovern had used an obscenity on the campaign trail in Michigan.

In a charged reply that reflected the emerging dichotomy between those who emphasized structural sin or personal piety, EFM’s Richard Pierard responded, “It appears that you and I fundamentally differ as to what comprises moral leadership. I gather that you regard the use of profanity (an action which I do not condone) as the greatest evil. For me, however, the napalming of Vietnamese children, the bugging of Democratic Party headquarters, and the widely publicized corrupt milk and grain deals are far more serious sins.” The mainstream evangelical standard Christianity Today, at its most stridently conservative in the early 1970s under the leadership of Harold Lindsell and J. Howard Pew, also signaled its preference for Nixon. Lindsell quoted Graham as saying that the incumbent “will probably go down in history as one of the country’s greatest presidents.”

The fawning support of Nixon by certain notable evangelical elites infuriated progressive leaders. Besides Graham, the most egregious case was Harold Ockenga, a long-time pastor in Boston and founding president of the National Association of Evangelicals. In a newspaper article written just one week before the election, Ockenga effused about the “high moral integrity” of his “personal friend” Nixon. Ockenga wrote EFM stating, “I for one cannot understand how any of you men of evangelical conviction can back Mr. McGovern.” Soon after, the local newspaper, the Hamilton-Wenham Chronicle, printed a gossipy report on the Ockengas’ attendance at the inaugural. Ockenga and his wife had chatted with the Rockefellers, Billy Graham, and Henry Kissinger at a formal dinner to which Mrs. Ockenga wore “a striking creation” by designer Oscar de LaRenta. It was a “formal, empire-waisted gown of a gold motif,” reported the Chronicle, “beautiful to behold.” Relieved that “the city was extremely calm—I really didn’t see any hippies” and pleased by “the number of times God was mentioned in the various events,” Mrs. Ockenga reported that attending the inaugural was “the greatest thrill of my life.”

Still, EFM organizers remained hopeful. They sensed a growing discontent toward Nixon among younger evangelicals. In an effort to make headway among evangelical middle, they began to emphasize McGovern’s evangelical credentials. They noted that McGovern’s father was a Wesleyan Methodist pastor who graduated from the evangelical Houghton College. EFM leaders similarly stressed their own evangelical theology. An early appeal letter, for example, read, “We continue to assert vigorously that Jesus of Nazareth rose from the tomb, that He is Lord of the Universe and that men can find genuine fulfillment only when the risen Lord Jesus regenerates and transforms selfish hearts.” These gestures culminated in an EFM-engineered McGovern appearance at Wheaton College, an impressive coup, given that twelve years before John F. Kennedy had not been permitted to rent the college gymnasium for a rally.

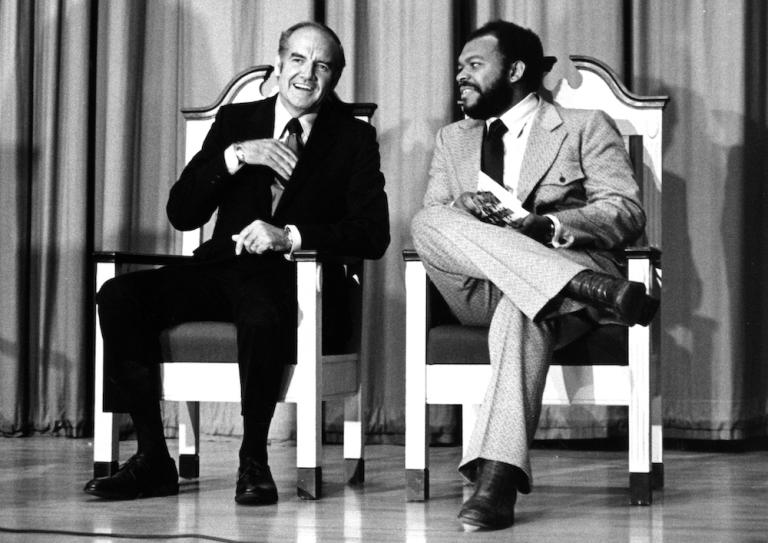

On October 11, 1972, McGovern took his campaign to the stage of Wheaton’s Edman Memorial Chapel. After being introduced by Tom Skinner, the candidate spoke fluent evangelical in front of an overflow crowd of over 2,000 during the Tuesday chapel service. McGovern explained that “in our family, there was no drinking, smoking, dancing or card-playing.” He would have attended Wheaton, he said, if his family could have afforded the tuition. He identified with the mid-century evangelical preoccupation with individual conversion and change: “As President, I could not resolve all the problems of this land. No President and no political leader can. For our deepest problems are within us—not as an entire people—but as individual persons.” Yet McGovern, affirming John Winthrop’s declaration on the Arbella in 1630 of America as a “city on a hill,” also stressed moral and spiritual leadership in the public square. “The wish of our forebears,” he concluded, “was to see the way of God prevail. We have strayed from their pilgrimage, like lost sheep. But I believe we can begin this ancient journey anew.” Citing evangelical icons such as Jonathan Edwards, John Wesley, and William Wilberforce, McGovern contended that his presidency would nurture conditions in which spiritual, moral, and social revival could occur. Faith, he declared in contradistinction to President John F. Kennedy’s careful delineation before a gathering of Protestant clergy in Dallas just ten years earlier, would very much shape his presidency. At the conclusion of his speech, McGovern received a standing ovation.

Opposition, however, tempered EFM’s delight. Several students booed, jeered, and hung a hostile banner from the chapel balcony. Others at Wheaton, reported journalist Wesley Pippert, seemed “suspicious of McGovern because of his liberal views and perhaps even more because he was once one of them, and in their opinion, he has strayed.” The candidate’s mixed reception by establishment evangelicals pointed to a much broader lack of success by EFM. By the date of the election on November 7, 1972, the organization had contributed negligible amounts—only $5,762 from only 358 people—to the coffers of a presidential campaign in desperate need of more money and votes. The cause had been taken up too late and by a group that lacked electoral experience and savvy. Moreover, it relied too much on young evangelical educators who could offer their moral support but little money. One New Jersey woman wrote EFM lamenting that “All the Christians we know are for Nixon, except a few young people who have no money.” From Athens, Ohio, came a letter that read, “I have no money for you (being a destitute graduate student with a huge obstetrics bill), but that which I have I give to you: a list of people who profess Christianity but are, regrettably, staying in the Nixon camp.” Though they did not mobilize as they would in 1976 and 1980, rank-and-file evangelicals helped carry the incumbent to a landslide victory—a 520-17 majority in the Electoral College and a 23 percent margin in the popular vote, the second largest margin in American history.

Despite the disheartening defeat, many in the evangelical left remained upbeat. After all, they had been working on behalf of a hamstrung candidate. Even moderate liberals, by a margin of over two to one, chose Nixon over McGovern as the candidate who best reflected high moral and religious standards. (Watergate tapes had not yet unveiled Nixon’s patterns of profane speech and corrupt governance.) Moreover, members of EFM had experienced the exhilaration of finding like-minded evangelical progressives. Collectively they had challenged the evangelical establishment and earned wide coverage of their political activism in the national press. Their mobilization effort was, in some respects, respectable given its late starting date just two months before the election. EFM had succeeded in its hope “that evangelicals as a group can be heard.”

Just a year later, as the dark shadow of Watergate eclipsed the Nixon presidency, EFM took on new significance. Board chair Walden Howard wrote to Sider that “I expect to see such a crisis in confidence as all of these things become public that it will be extremely difficult for President Nixon to govern. The unredeemed part of me is licking its chops, but the better part of me feels sad for our country. Would to God that McGovern had been elected! We would certainly be in a very different position today.” But McGovern had not won, so the nascent evangelical network instead capitalized on growing disillusionment with Nixon.

Next time . . . on how that disillusionment sparked a surprisingly strident call for a new social conscience. The Chicago Declaration, written on Thanksgiving weekend of 1973, would birth an organized evangelical left.