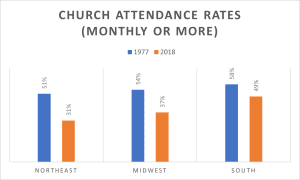

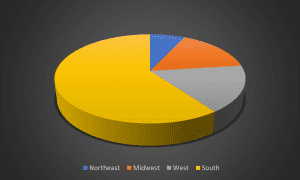

Fifty percent of all people in the United States who attend church at least once a month live in the South, according to data from the 2018 General Social Survey. A half-century ago, when more than 50 percent of people in both the Northeast and the Midwest claimed to go to church at least once a month, differences in church attendance rates between various regions of the country were barely noticeable. But today the South – along with the lone Mountain West state of Utah – remain the only places in the country where regular church attendance rates are even close to 50 percent.

This means that American Christianity as a whole has been southernized. If we took all churchgoing Christians of any denomination – Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox, along with the now massive category of “nondenominational,” which accounts for nearly twice as many adherents as the entire Southern Baptist Convention – fully half of those people would be southerners.

And if this is true of Christianity as a whole, it is even more true of evangelicalism. Of all the developments that have influenced the political and cultural turn of American evangelicalism over the past half century, one of the least noticed – but perhaps most significant – factors has been the rapid decline of nearly all varieties of northern Christianity since the 1970s and the corresponding increasing cultural influence of evangelicalism’s rural southern manifestation. Sixty percent of American Protestant churchgoers who claim a born-again experience and believe that the Bible is either the “word of God” or “inspired of God” live in the South, according to the 2018 GSS survey. (I should note that this figure drops to 55 percent if we restrict our analysis only to white Protestants – thus leaving out the millions of African Americans who have also been born again and who have evangelical beliefs, even if they are not usually classified as “evangelical” in sociological or historical analyses).

Keep in mind that the General Social Survey is not measuring people’s self-identification as “evangelicals,” a word that is fraught with cultural controversy and that may have lost much of its original meaning. The term “evangelical” was never used in the General Social Survey questions. Instead, this survey indicated that 60 percent of all American Protestants who have been born again, take a generally high view of scripture, and regularly attend church live in the eleven states of the former Confederacy or in one of a handful of border states, such as West Virginia and Kentucky, that are now commonly classified as southern. Church attendance in general is associated disproportionately with the South, and evangelical beliefs and practices in particular are even more so.

The shift of Christianity to the South has profound implications for how we think about American evangelicalism’s shift to the political and cultural right. Too often, we have tended to tell the story of American evangelicalism’s history over the past century as though it were the story of a single religious tradition changing over time and becoming more politically conservative.

And when we tell that history, we usually begin the 20th-century story with the fundamentalist-modernist controversies in northern denominations, followed by the rise of the National Association of Evangelicals, the creation of Christianity Today magazine, the political mobilization of evangelicals in southern California, the rise of the Moral Majority, and the support of evangelicals for Trump – without noticing, perhaps, that in the course of presenting this narrative, we have shifted our geographic focus from New York City in the 1920s to Chicago in the 1940s to the Sunbelt in the postwar era, and finally to the rural South. I have been just as guilty as anyone else of giving insufficient attention to this geographic shift, but I now think it may be more significant than I previously realized. As we surely all know by now, the United States is not politically or culturally homogenous, so when we shift regions, we should not assume that the “evangelicals” we might meet in mid-20th-century Chicago are the same type of “evangelicals” we might encounter in the postwar Sunbelt or the early 21st-century rural South.

What if we instead told the history of American evangelicalism as a story not of a single group of people but of various regional coalitions entering and exiting the movement over time? Right now, the southern rural wing of evangelicalism has unprecedented political influence, but that was not always the case, even during the early years of the New Christian Right. The story of American evangelicalism’s political shift during the past half century cannot be fully understood without an account of how white southerners became a majority in the evangelical coalition and how evangelicalism in other regions of the country faded in influence. For the sake of space, I’m going to skip the early 20th-century part of this story and begin the story in the mid-1970s, just before the rise of the New Christian Right, and look at what happened to the two major centers of evangelical influence at that time.

The Declining Influence of Midwestern Evangelicalism

A half-century ago, the South – or, rather, the Sunbelt, and especially southern California – was only one of the nation’s centers of evangelicalism. The second leading center was the Midwest – especially the Chicago area, with smaller centers of evangelicalism also found in Grand Rapids, Minneapolis, and the rural heartland of Indiana and Ohio. In 1977, 27 percent of all white Protestants who attended church at least once a month and identified their theology as either “fundamentalist” or “moderate” lived in one of five states of the eastern Midwest: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Most of the major evangelical publishers, such as Zondervan, Intervarsity Press, Eerdmans, and a number of others, were headquartered in this area. So was Christianity Today. This was also the regional center of much of evangelical education. Wheaton College and Calvin College (now Calvin University) were located in this region, as were twenty-four other Christian colleges now affiliated with the CCCU. The National Association of Evangelicals was founded in this region. And in the 1970s, it was this region that produced one of the nation’s best known megachurches: the Willow Creek Community Church.

Indeed, so prominent was the Midwest in the formation of twentieth-century American evangelicalism that several histories of American evangelical culture in the mid-20th century (such as Joel Carpenter’s Revive Us Again or George Marsden’s Fundamentalism and American Culture) focus almost entirely on the northern (and mostly midwestern) story and say almost nothing about the South.

But today the center of influence in American evangelicalism has left the Midwest and moved to the South. In 2018, only 17 percent of white Protestants who attended church at least monthly and identified their theology as either “fundamentalist” or “moderate” lived in the eastern Midwest – a decline of ten percentage points over the previous four decades.

This shift away from the Midwest toward the South is partly due to population trends: Much of the Midwest experienced a relative population decline in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, while the South experienced population growth. But there’s more to the story than simply a demographic shift. The Midwest, along with the rest of the North, also experienced a drastic decline in church attendance rates. In 1977, 54 percent of Midwesterners attended church at least once a month. By 2018, only 37 percent did. The South also experienced a decline in church attendance, but only from 58 percent to 49 percent. That means that in 1977, the South’s church attendance rate was only 4 percentage points higher than the Midwest’s, but by 2018, it was 12 percentage points higher.

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives’ (ARDA’s) religion census reports, the decline in religious affiliation in the Midwest came almost entirely from Catholic and mainline Protestant churches; the congregations that the survey classified as “evangelical” experienced at least modest membership growth. We therefore might be inclined at first to say that midwestern evangelicalism has remained strong.

But in actuality, the type of evangelicalism that is growing in the Midwest is not the type of evangelicalism associated with the intellectual and institutional fixtures that are usually given prominence in histories of mid-20th-century evangelicalism – that is, institutions such as Wheaton, Calvin, Christianity Today, and the leading evangelical publishing houses. Although the leaders of those institutions had beliefs that were thoroughly evangelical according to the standards of David Bebbington’s quadrilateral, their church membership was, as likely as not, in congregations associated with the conservative wing of mainline Protestantism. Carl Henry, the first editor of Christianity Today and a person who was arguably the leading evangelical theologian of the mid-20th century, was a member of the American Baptist Church, a denomination that ARDA, whether rightly or wrongly, classifies as mainline Protestant rather than evangelical. Many of the other leading lights of mid-20th-century northern evangelicalism were likewise members of denominations that today would be considered mainline Protestant.

When I first visited the Wheaton College campus a number of years ago, I was at first amazed that most of the churches that I saw within a few blocks of campus were venerable old mainline Protestant churches – especially Presbyterian and Methodist. But then I realized that for much of the 20th century, Wheaton’s leadership and support came disproportionately from churches that were very much part of mainline Protestantism, even if their adherents were evangelical in their theology. The rapid decline of mainline Protestantism in the Midwest has therefore had a severe effect on Midwestern evangelical institutions.

Evangelicalism is growing in the Midwest, but it’s not a type of evangelicalism that has historically been associated with institutional leadership in an evangelical movement. In Kent County, Michigan (the county where Calvin University is located), members of churches that ARDA classified as evangelical made up a slightly larger share of the population in 2010 than in 1980, but most of that growth came in the form of charismatic and nondenominational churches rather than in the Reformed churches that had long supported Calvin. The percentage of county residents who were members of the Christian Reformed Church in North America (Calvin’s denominational affiliation) declined from 9 percent to 7 percent during this thirty-year period, while the number of county residents who were members of the Assemblies of God more than doubled. By 2010, there were more members of nondenominational evangelical churches in Kent County than in all of the county’s CRC congregations combined.

And if this is happening in Grand Rapids, the same thing is occurring in other parts of the Midwest. Evangelical Christianity is thriving among many first and second-generation immigrants and among other people who are flocking to community churches and leaving organized denominations behind. But the decline of non-charismatic Protestant denominations and Catholic churches in the Midwest has outpaced the growth of nondenominational evangelical churches, thus leading to a reduced church attendance rate overall – and this has had a severe effect on the influence of Midwestern evangelical institutions.

Because midwestern evangelicalism was so closely associated with mainline Presbyterian, Methodist, and northern Baptist denominations that experienced sharp declines in affiliation and attendance in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the decline of church attendance in general in the Midwest – and especially in established Protestant denominations in particular – meant that Midwesterners would comprise a much smaller percentage of the American evangelical population in the 21st century than they had in the mid-20th.

The Rise of Sunbelt Evangelicalism

If midwestern evangelicals had been asked in the late 1970s which region they thought would replace the Chicago area as the center of influence in American evangelicalism, they would have undoubtedly said the Sunbelt. Southern California – the home of Ronald Reagan, James Dobson, Tim LaHaye, and a plethora of evangelical colleges – was home to some of the nation’s fastest-growing evangelical institutions and megachurches. It was also where Billy Graham had first made national headlines with his Los Angeles crusade in 1949. And in rapidly growing southern metropolitan areas, such as suburban Atlanta, upwardly mobile middle-class whites were flocking to Baptist churches and fusing Republican Party politics with an evangelical gospel.

Midwestern evangelicals had always been Republicans, but their brand of Republican Party conservatism was more closely identified with the fiscal conservatism of Gerald Ford (whom large numbers of midwestern evangelicals had supported in 1976) than with the Sunbelt conservatism of Ronald Reagan or the culture-war politics of Jerry Falwell. They were thus not entirely sure at first what to make of a Christian Right that was so closely associated with a Sunbelt brand of politics that was somewhat different from their own.

Nearly all of the leaders of the Christian Right were based in the South or in southern California. There was no Chicago-area evangelical leader who became a nationally known Christian Right voice in the way that Jerry Falwell did. A few Christian Right leaders such as Tim LaHaye had once been connected with the Midwest, but by the time they embraced Christian Right activism, they had long ago cut those ties and become products of the Sunbelt.

As products of the suburban Sunbelt, they were upwardly mobile. At a time when the industrial states of Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan – the center of northern evangelicalism – were experiencing economic declines and population losses, the Sunbelt was rapidly growing and leaving the Rust Belt behind. The megachurches most attracted to Christian Right activism were suburban churches comprised of upwardly mobile whites who sensed that they had the political power to stop the social trends of the 1960s and 1970s that they considered disturbing. As relatively new converts to the suburban, Sunbelt version of conservative Republican politics, they found it easy to conflate their version of Christian moralism, Christian nationalism, and evangelical identity with support for Ronald Reagan and unregulated capitalism.

The responses of midwestern evangelicals were mixed. Bill Hybels, the founding pastor of Willow Creek Community Church, never embraced the Christian Right and ultimately became a close ally of President Bill Clinton. Some of the Calvin faculty, such as Nicholas Wolterstorff, campaigned for a social justice agenda that was at odds with the political priorities of the Republican Party.

But as a whole, midwestern evangelicalism remained generally connected to the GOP – and certainly connected to the evangelical coalition that was now increasingly dominated by the Sunbelt – because the brand of evangelical Republican politics that the Christian Right embraced was compatible with the morally conservative Protestant political agenda that the evangelical leaders in the Midwest had long supported. The Christian Right of the late twentieth century may not have been the invention of the evangelicals in the Chicago suburbs or the Republican precincts of Grand Rapids, but it was not entirely alien to their thinking either. Its leadership came from middle-class white suburbanites who were just as upwardly mobile and educated as the evangelicals in the Chicago suburbs.

So, for another three decades after the center of evangelical influence shifted from the Midwest to the Sunbelt, the evangelical midwestern institutions remained in alliance with Sunbelt evangelicalism. If, as George Marsden said, an evangelical was someone who liked Billy Graham, both Sunbelt evangelicals and midwestern evangelicals found they could agree on Graham, who maintained strong institutional ties to both regions. (Although his home was in Charlotte, North Carolina, his ministry headquarters were in Minneapolis – where he had served as a college president – and he was a Wheaton grad). But this interregional alliance was strained to the breaking point in the 21st century when the center of influence in Christian Right politics shifted once again – this time from the Sunbelt to the rural South.

The Rise of the Rural South in the Evangelical Coalition

During the past decade, the geographic center of influence in both the Republican Party and in politicized white evangelicalism has shifted from the suburbs to lower-income, less educated rural counties. In 1980, the vast majority of the Republican Party’s southern support – and, by extension, the Moral Majority’s influence – was concentrated in middle-class suburban areas. In Georgia, Cobb County, located on the northwest side of metro Atlanta, was an early convert to the Republican Party. So were the suburbs of Birmingham. But the rural counties in most of the rest of the state did not support Reagan. Carroll County, the west Georgia county where my university is located, voted for the Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter in 1980, as did nearly all the surrounding counties in this largely rural region of the state. Most of the northwest Georgia counties in what is now Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s district also voted for Carter.

Today much of rural Georgia – including my home county, which now votes Republican in every election – is represented in Congress by Trump-supporting election deniers, but in 1980, the voters in these regions did not support Ronald Reagan. Nor was this phenomenon confined to Georgia. Across the South, many of the poorest, most rural counties voted against Reagan, even when they had a white majority. Carter carried most of the counties in West Virginia, northern Kentucky, western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and east-central Arkansas.

But today these rural areas are overwhelmingly Republican, and the suburban Sunbelt counties that gave the GOP the strongest support in the 1980s and 1990s now vote Democratic. In 2020, the Sunbelt metropolitan areas where white evangelicals overwhelmingly supported Ronald Reagan in 1980 – including places such as Orange County, California; Cobb County, Georgia; and Lynchburg, Virginia – voted for Joe Biden rather than Donald Trump. And conversely, the lower-income, white rural counties that voted against Reagan in 1980 were the places filled with Trump supporters. My own county, for instance, voted for Trump over Biden by 78 percent to 21 percent – a figure that closely corresponds to the racial makeup of the county, which is 19 percent Black, 4 percent Hispanic, and 69 percent non-Hispanic white. And what’s true in Carroll County, Georgia, is true across the rural South. While Biden won the Sunbelt suburban South (carrying Cobb County, the district that Newt Gingrich once represented, by 56 percent), he won hardly any white votes in the rural South.

All of this might have made little difference for evangelicalism if church affiliation rates among college-educated whites in the metropolitan areas of the Sunbelt had remained strong. After all, the rural South was just as churched in 1980 as it is today, but its political opinions and cultural views exercised little influence over either the Christian Right or mainstream evangelicalism in general, because its voices were drowned out by churchgoing Protestants in the many other regions of the country where evangelicalism still had a significant presence. (If the coal miners of Appalachia and the rural whites in places like Carroll County, Georgia, had exercised more political influence over evangelicalism in 1980, the Christian Right’s alliance with Reagan might not have been as strong as it was).

But the suburbs of the Sunbelt have become more racially diverse than they were in 1980. Hispanics now make up 34 percent of the population of Orange County, California – up from 15 percent in 1980. Cobb County, Georgia, is now 14 percent Hispanic and 29 percent Black; in 1980, Blacks comprised less than 5 percent of the Cobb County population. So, although the religion census indicates that membership in evangelical churches in these counties has held steady over the past few decades, these are not the same sort of evangelical churches that gave rise to the Christian Right – and they may not even be the sort of churches whose members think of themselves as “evangelical.” They’re likely to be multiracial community churches and charismatic Hispanic congregations. If we’re looking for white evangelicalism in particular, we’re not as likely to find it in the southern Sunbelt. The college-educated whites in these suburbs may be less likely than their parents were to go to church, and the people who are in church are less likely to be white.

So, to find white evangelicals of the type that pollsters are looking for when they survey the opinions of white evangelicals, we have to go to the rural South, where there are just as many white evangelical churches as there were a generation ago. Not surprisingly, therefore, when white evangelicals are asked about their political opinions, the overwhelming majority support Donald Trump – because the majority live in the South (and especially the rural South), where Republican voting has been deeply entrenched as a cultural phenomenon for the past generation and where all signs indicate that it will only increase now that the Republican Party is thoroughly infused with the right-wing populist politics that Trump has channeled.

At this point, a number of college-educated evangelicals in the Midwest – and a few in the urban or suburban Sunbelt – have started to publicly muse about abandoning the term “evangelical” and maybe leaving the evangelical coalition altogether, now that it has become associated with a brand of politics that they consider highly objectionable and likely un-Christian.

“This election, I didn’t personally know any evangelicals who were vocally supporting Trump,” former Christianity Today managing editor Katelyn Beaty wrote in November 2016. She was therefore aghast when she found that 81 percent of white evangelical voters cast their ballots for a candidate she found the very antithesis of the values of Jesus, and she questioned whether she could remain within evangelicalism at all. “At some point you have to get up and leave the table,” she concluded.

As a Calvin University graduate and editor of a magazine based in the Chicago suburbs, Beaty’s experience with evangelicalism had been heavily influenced by midwestern evangelical institutions that had long considered themselves the center of American evangelical thought, but by 2016, it was clear that their theological and cultural views were out of step with the majority of voters that pollsters had identified as white evangelicals.

Should Evangelicals Outside of the Rural Southern Evangelical Coalition Despair?

The picture that I have painted suggests that midwestern white evangelicalism declined because the decline in mainline Protestantism also affected white evangelicals and that Sunbelt evangelicalism declined because the Sunbelt became more racially diverse, with younger college-educated whites in the metropolitan Sunbelt less likely than their parents to go to church and with some of the white congregations in Sunbelt suburbia being replaced with multiracial nondenominational megachurches. As a result, what’s left of white evangelicalism is disproportionately associated with the rural South.

If you’re an evangelical who is not a rural white Trump-supporting southerner, this might seem like reason to despair. But I don’t think it is.

It’s rather a reason to realize that what is happening is not either a decline or corruption of a monolithic “evangelicalism,” but rather a fragmentation of a coalition that was always more culturally diverse than many assumed. Demographic and religious affiliation trends have produced a situation in which the majority of born-again Christians active in church now live in the South. If only the white people in this group are polled, their political views are likely to be overwhelmingly conservative – just as the views of most white southerners are, whether they attend church or not.

When midwestern evangelicals dominated the evangelical coalition, the political views of institutional evangelicalism (e.g., the National Association of Evangelicals) closely reflected the views of white midwestern Protestants, whether evangelical or not. When Sunbelt evangelicals dominated the evangelical coalition, the political and economic views of the evangelicalism that the media was most familiar with were not far removed from the political priorities of middle-class whites in the Sunbelt. Now that rural white evangelicals comprise a disproportionately high share of the total number of white born-again Protestants in the nation, should we be surprised that polls of evangelicals suggest that their political views reflect the concerns of most rural southern whites. Why should this be surprising?

Unfortunately for evangelicalism, the dominance of rural white southerners in this coalition has occurred at a moment when the politics of the rural white South is becoming far more vocally right wing than it has been in several generations and when some of the institutions associated with northern evangelicalism are becoming more politically progressive on issues like the environment, race, and economics – issues that reflect the concerns of many other college-educated northerners. The National Association of Evangelicals and the Southern Baptist Convention are moving further apart in their politics, and they no longer have the politics of the suburban Sunbelt to hold them together.

But if you’re an evangelical who identifies more with the NAE than with the SBC, you don’t have to wring your hands in despair or slam the door on evangelicalism in disgust. Instead, in all likelihood, if you’re in a large urban area, you can easily find a number of churches that combine a historic evangelical Protestant theology with a progressive social ethic – and they may even be multiracial. And you can find a number of evangelical institutions that embrace this progressive vision. If you serve the Lord in such a place, you don’t have to worry about how the white evangelicals in other churches and other regions are voting. As long as church affiliation is declining in the North and holding reasonably steady in the rural South, polls will continue to show that an overwhelming majority of white evangelicals hold political views that are deeply at odds with the views that are widely held in most urban areas, but that shouldn’t surprise us – nor should it cause us to question our own theological beliefs, as though evangelical theology must inevitably lead to political conservatism.

And what if you’re in the rural South? Even here, born-again Christianity has not entirely sold out to the MAGA crowd – but you might have to go outside of a white church to find that out. Throughout the South, the group most likely to be born again, hold to a high view of the Bible, and be in church on Sunday are Black southerners – and very few of them vote Republican.

Born-again Christianity can easily take on the political contours of whatever cultural group embraces it, and if that group happens to be whites in the rural South, the version of evangelicalism they espouse will look very right-wing. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Perhaps instead of merely lamenting the politics of the white rural South, those of us who believe in evangelical theology but not white southern evangelical politics should pray for the gospel to spread in politically progressive areas – because when it does, it’s not likely to be allied with political conservatism.